'Pygmalion' is 100 years old: Happy Birthday, dear Eliza

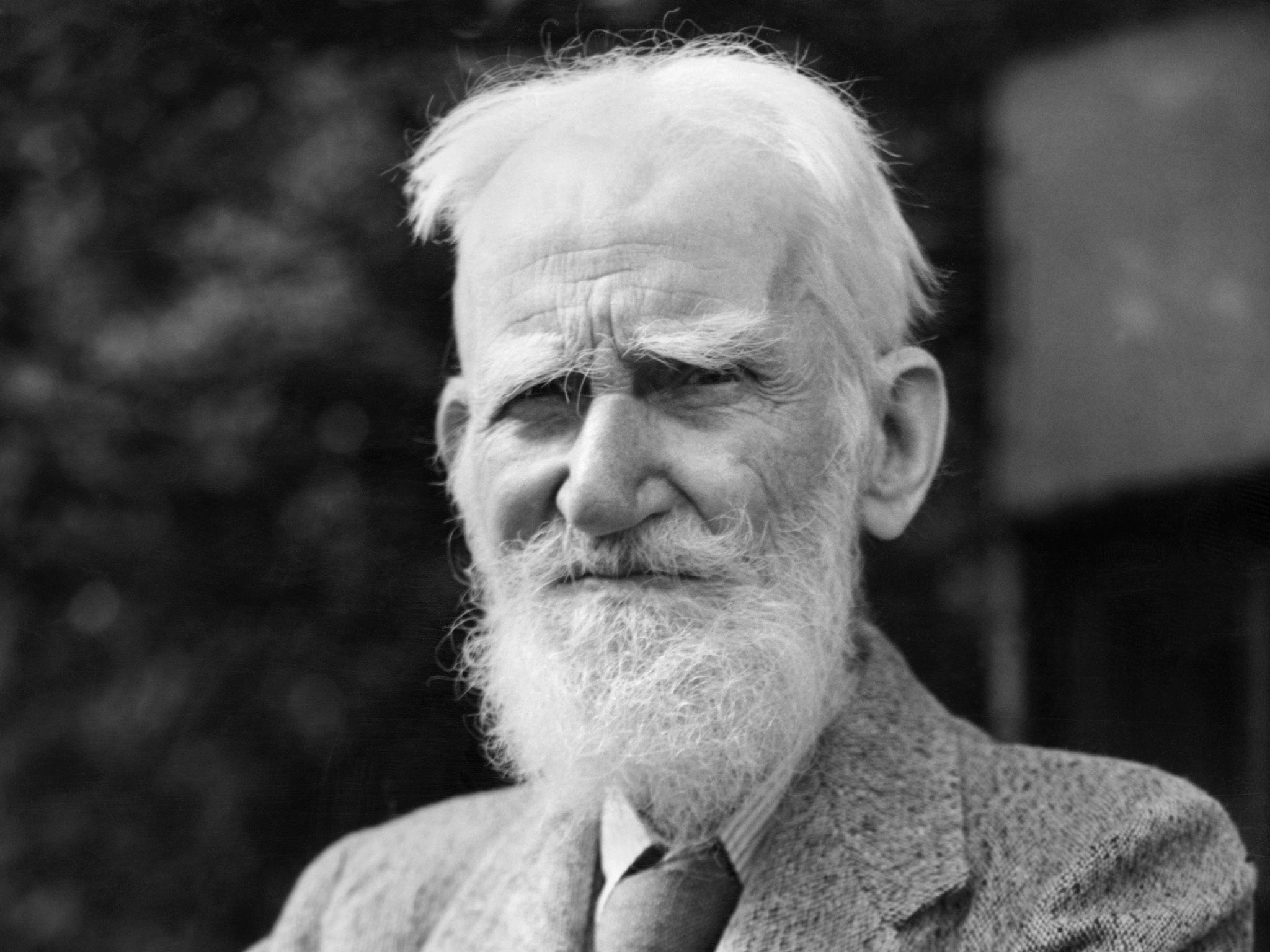

Michael Holroyd tells the story of Pygmalion's conception, and how its author was smitten by his leading lady

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.George Bernard Shaw wrote Pygmalion between March and June 1912, but it's opening night in London was on 11 April 1914 – almost 100 years ago, and some 15 weeks before Britain declared war on Germany.

In a culture of increasing competition, countries were extending their empires by winning wars; and individuals were improving their places in society through the acquisition of money. Shaw ridicules the random absurdity of vast incomes with the story of an elderly dustman who has the appropriate name of Doolittle. As the result of a joke describing him as England's most independent moralist (rather like Shaw himself), he is left a fortune and obliged to deliver improving lectures every year. He describes himself as ruined by money.

Shaw's ideal, which he wished to impose on the 20th century, was equality. He did not mean the political clichés of equal opportunities and level playing fields. What he looked for was something nearer equality of income and equality of accent. "The reformer we need most today is an energetic phonetic enthusiast," he wrote in the preface to his play. Such methods of cutting down social barriers were his gesture towards removing the power for change from financiers and fighting men. His dream was of a revolution without bloodshed or misery.

Henry Higgins'social experiment, turning an East End flower girl into a West End lady, reaches a very different conclusion from the story in Ovid's Metamorphoses where the legendary King Pygmalion made a statue of a girl with whom he fell in love when it came to life. "A Romance in Five Acts" was Shaw's subtitle to his play. But he enjoyed describing it, not as a romance, but a didactic attempt to show how the science of phonetics could pull apart Britain's antiquated class system. However, the autobiographical subtext to his play became a strong undercurrent that threatened to carry this theme out of his control.

The voice tests that Higgins gives Doolittle's illegitimate daughter Eliza are a foretaste of the respectable voice tuition given to prime ministers Edward Heath and Margaret Thatcher. They also bring to mind the singing lessons Shaw's mother had in Dublin. Her teacher, George Vandeleur Lee, was a Svengali-like personality and a Catholic. Mrs Shaw moved her Protestant family into his superior Dublin house and in 1873 followed him to London, leaving her 16-year old son with his semi-alcoholic father George Shaw. The adolescent boy began to wonder which George he had been named after. Was he, like Eliza Doolittle, illegitimate? Illegitimacy carried far greater moral opprobrium than it does today.

The painful relationship with his mother left Shaw feeling unlovable and he developed a need for public attention to take the place of love. Orphaning himself from his family, he became the child of his writings, a 20th-century celebrity with the brand name GBS. He omitted the worrying name George from his publications – and instructed friends: "Don't George me."

In his relationships with women he used a witty self-assertive style as a means of self-protection. Of all the actresses he knew, the most seductively magical was Mrs Patrick Campbell – or Stella as he called her. He wanted her for his play-world and persuaded her to play Eliza.

Early in 1913, Shaw's mother died. It was as if the source of her son's unlovableness and need for emotional protection vanished. He found himself violently in love with Stella – something he had never experienced before, not even with his wife Charlotte. He was in his mid-fifties and she was in her late forties – but what did age matter? It mattered perhaps because Stella was thirty years too old to be Eliza.

Her husband had died in 1900. She was nearing the end of her acting career and, as so many women were obliged to do, she was looking for the security of marriage and a safe place in society. Not many playwrights wrote parts for middle-aged and elderly women. Stella was charmed by Shaw taking so many years off her age. But she escaped his advances and, during rehearsals, took a few days off to marry George Cornwallis-West – another George, and with a hyphenated name like the brainless Freddy Eynsford-Hill in the play. Shaw was deeply wounded. Of his 57 years, he wrote, "I have suffered 20 and worked 37. Then I had a moment's happiness … I risked the breaking of deep roots and sanctified ties … what have I shrunk into?"

The rehearsals and many later productions of Pygmalion became a nightmare for him. Everyone wanted Eliza to marry Higgins. But he strongly objected (as he objected to the idea of his mother having a love affair with George Vandeleur Lee). He wanted Eliza to have employment and teach phonetics. That was the feminine equality he sought. He re-wrote passages of the play to make this clearer. But the stage directions point to a sexual relationship that helped future directors get round his objections. Nothing seemed to go his way. Even when he won an Oscar for the screenplay of Pygmalion in 1939, additional romantic dialogue had, unknown to him, been inserted.

Shaw could, however, congratulate himself on having won a major battle. When Franz Lehár proposed making a romantic musical of Pygmalion, Shaw strongly rejected the proposal. It was not until six years after his death, in 1956, that My Fair Lady came into being.

Despite these many difficulties, Pygmalion has become Shaw's most popular play. It is focused both on the past and the future, coming from autobiographical sources in his early years and carrying his vision of a classless future without unemployment and excessive incomes. When a modern audience sees Eliza's predicament it asks: why can't Eliza marry Higgins and have a job? That was not a valid question a century ago. µ

'Pygmalion', Yvonne Arnaud Theatre, Guildford (01483 440000) to Saturday then touring to 21 June (pygmalionuktour.co.uk)

Michael Holroyd is George Bernard Shaw's authorised biographer. Re-produced by kind commission of John Good Ltd, publishers of the 'Pygmalion' programme

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments