The Old Vic at 200: Celebrating the theatre's golden legacy

On the bicentenary of the Old Vic, David Lister looks back at the theatre’s golden age, inspired by Laurence Olivier's Othello performance and its later rebirth under Kevin Spacey

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.They settled in for the night in their sleeping bags opposite Waterloo station. Night after night. But these were not the poor sleeping rough. These were reasonably affluent theatregoers hoping to get tickets the next morning to see Laurence Olivier in Othello.

When Olivier used the Old Vic for most of the 1960s for his fledgling National Theatre company, he also founded a golden age in the history of a building that has had a number of golden ages. Anyone who can remember those years knows how exciting they were. The company not only starred Olivier, but the likes of Maggie Smith, Joan Plowright, Albert Finney, Lynn Redgrave, Derek Jacobi, Frank Finlay, and ambitious, young bit-part players such as Michael Gambon and Anthony Hopkins.

World class directors like Franco Zeffirelli and Ingmar Bergman would come to impart their brand of colour, spectacle and magic in an era when traditional theatre, particularly at that address, proved as exciting and mould-breaking as much of the counter culture going on elsewhere.

As a young boy I was lucky enough to see Olivier on stage in his last years, and I have never experienced such charismatic and electric stage presence in many years of theatregoing since.

As the Old Vic celebrates its bicentenary with an open house, street party and variety night on Saturday 12 May, it can look back with enormous pride on those golden years.

But in such a long history, Olivier’s 1960s company was not the only period of excitement and acclaim. I would argue, as perhaps few will dare to, that the recent decade long tenure of Kevin Spacey also should be remembered for its artistic success.

I was present when the Old Vic chief executive Sally Greene introduced Spacey to a selected number of arts journalists at a lunch at The Ivy. For a slightly bizarre reason, the two of us got on. He was making a biopic of the singer Bobby Darin, and I was the only person at the table to have heard of Bobby Darin. A guilty pleasure.

Spacey’s first season in charge was decidedly mixed, and I wrote as much in the pages of The Independent. To my surprise, I received a two-page handwritten letter from him arguing his case and explaining his artistic policy. He had a passion for his art, and that should not be forgotten in the obituaries written for a career that ended perhaps rather too early.

After that first season he went from strength to strength. Sally Greene, in her programme notes for Spacey’s last performance, did him no favours by ranking his tenure alongside Olivier’s. But it was still a sparkling decade, and while it is right that he takes responsibility for the sexual assault allegations against him, it is odd that the board who praised him to the skies, takes none.

I had a particular reason for interest too, when Spacey’s successor and current artistic director, Matthew Warchus was appointed. I was at a lunch with Warchus more than 10 years earlier and he told me he had just been appointed artistic director of the Old Vic. A couple of weeks later Spacey’s appointment was announced.

At Warchus’s second coming I wrote that he had in fact been artistic director before, even if only for a matter of days. All his ‘people’ denied it, it was not mentioned on any of the publicity material, and you will still not find it mentioned on the Old Vic website. But he was gracious enough to invite me in and explain that it was indeed true, but Sally Greene had then decided on Spacey and he had at the same time decided to work abroad for a while.

Well, high drama and intrigue combined with great art has been a feature of the Old Vic’s 200 years. The theatre opened on 11 May 1818 and cost the princely sum of £12,000. Princely being an apposite word as the foundation stone had been laid two years earlier by Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg and Princess Charlotte of Wales.

Indeed, the theatre was originally called the Saxe-Coburg. Just a few years after the opening the theatre took a decidedly ultra-modern turn, installing a mirrored curtain on the stage. With 62 mirrored panels in a gilt frame, it would probably be a tourist attraction right up until today, but was sadly quickly dismantled after it was deemed a hazard.

It was in the 1830s that the real business of theatre really got going, with names we would recognise today. Edmund Kean played all four of Shakespeare’s main tragic heroes over six nights, a remarkable run, made even more remarkable by his declaring to the audience: “In my life I have never acted to such a set of ignorant, unmitigated brutes as I have before me.”

And that was before the invention of mobile phones.

The theatre was soon renamed the Royal Victoria after the then queen (which makes, when you think about it, the current name sound a tad disrespectful). And it became one of the first theatres to do what is now commonplace – issue a mission statement.

The Royal Victoria would henceforth be for “the encouragement of native talent”, a mission that now sounds almost Brexitesque.

But it worked. The theatre became noted for bringing the art form to “the common people” as the Old Vic today records on its website, and Charles Dickens wrote that “Whatever changes of fashion the drama knows elsewhere, it is always fashionable in the New Cut.” (A reference to the London road, since renamed The Cut, on which the theatre is located).

And if nothing else, that has remained true. The Old Vic, slightly off West End geographically, has rarely failed to be a trendsetter, attracting the top talent and rarely failing to be a hot ticket.

But it was really after the 1850s when Dickens wrote that accolade, that the Old Vic found the cutting edge that has never really left it since. And that was down to the first of the domineering and truly legendary personalities to make it their own and transform it into their image.

That person was Lilian Baylis. So let us pass over intervening events such as more changes of name including the dropping of the word theatre as it had ‘impure’ associations, and the somewhat unfortunate incident of someone shouting fire in the auditorium, when there was no fire but there was a stampede for the exit and 16 people died.

So to Lilian Baylis, appointed theatre manager at the tender age of 23 (it helped that she was the niece of the owner). But, nepotism apart, the appointment proved inspired. Baylis, as well as diversifying into opera and championing it in English, and presenting both opera and ballet alongside plays, she established a Shakespeare company at the theatre, and called the theatre by its present name, the Old Vic being a local nickname for the building.

In the early 1930s John Gielgud became acknowledged as the star of the Shakespeare Company, though there were many stars, not least Peggy Ashcroft and Ralph Richardson. In the late 1930s Olivier joined the company, and it is worth pausing to consider the events of 25 November 1937, and perhaps the reason why actors since have considered it unlucky to say the title of the Scottish play.

On that day Lilian Baylis died. It was the day of the dress rehearsal for Macbeth with Olivier in the title role. He just missed injury when a stage weight crashed down beside him. In the event, the opening was postponed as both the director and lead actress were in a car accident. And when it did open it started late, and Lilian Baylis’s portrait promptly fell of the wall.

Olivier’s second coming at the Old Vic as director of the National Theatre in the 1960s lasted until the NT found its permanent home close by on the South Bank. The last performance at the Old Vic was a tribute to Lilian Baylis, in which Peggy Ashcroft playing her, repeated Baylis’s threat to come back and haunt the theatre if her work were ever to be put at risk.

The theatre then became home to different owners and different artistic directors, including stalwarts of British theatre such as Peter Hall and Jonathan Miller.

Spacey’s appointment in 2003 ushered in an era which was in its own way also fascinating. It was not just that he could call on his Hollywood contacts such as Jeff Goldblum to star in David Mamet’s Speed the Plow, he also introduced innovation at the theatre such as staging performances in the round, notably a revival of Alan Ayckbourn’s The Norman Conquests, staging all three plays in one day, and he opened The Old Vic tunnels nearby to stage performances and events in the underground space, wooing a young audience.

Each generation will have its own memories of performances that have stirred them and left an indelible print on the memory. Maybe it was Olivier’s towering and hypnotic performance in Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night.

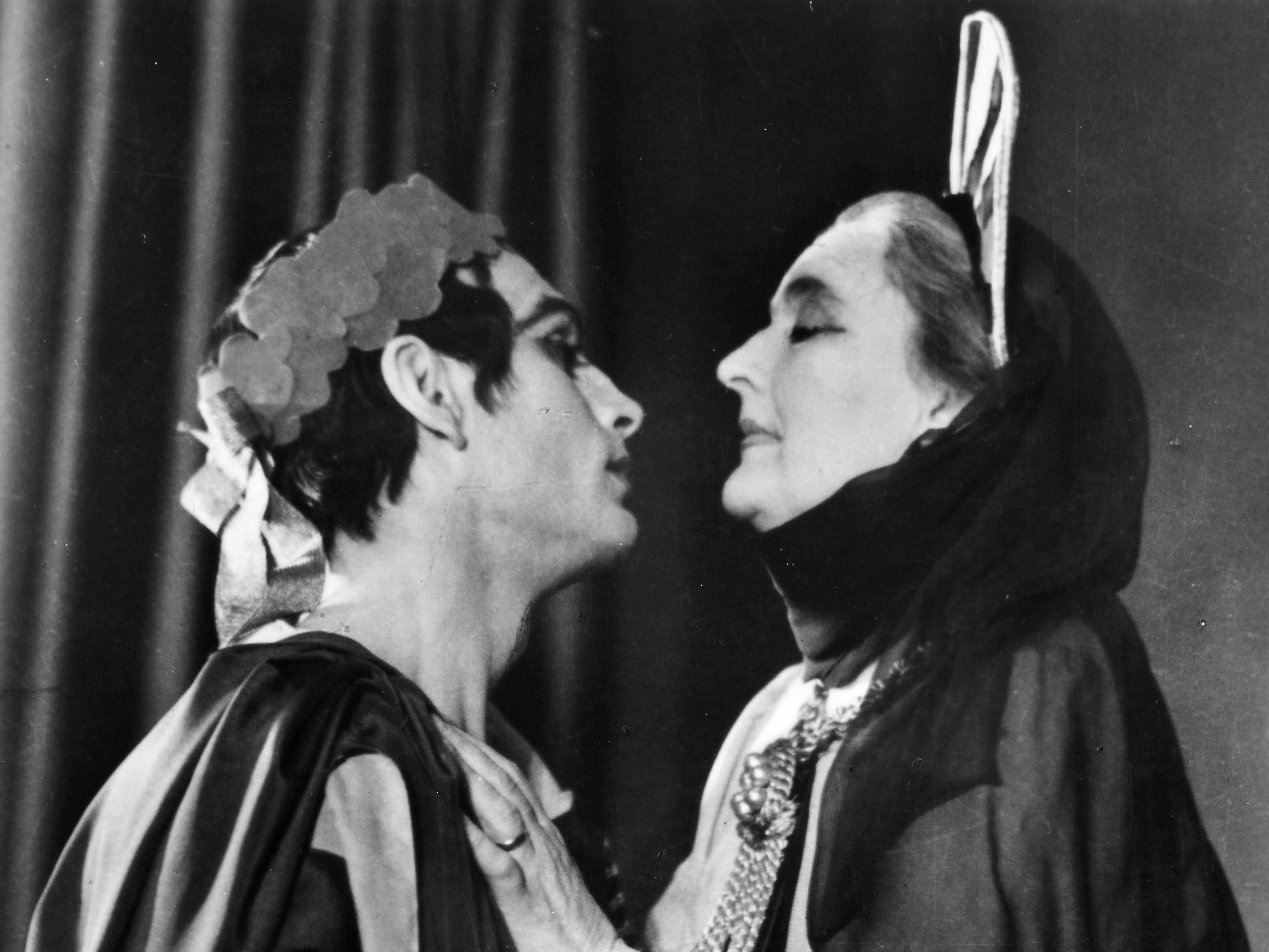

Maybe it was Maggie Smith as Hedda Gabler directed by Ingmar Bergman, a production which prompted Smith, unusually, to take fire at the critics, saying that she wished a woman could review the show as a woman “would understand about Hedda.” Or maybe the very young of today will always remember the current, acclaimed production of A Christmas Carol, being revived this Christmas.

It is the theatre that keeps on giving.

David Lister is the former arts editor of The Independent

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments