Julius Caesar: Paying tribute to a timeless tale of intrigue, ambition and assassination

King Lear, Hamlet and Othello all have good endings, but it is Julius Caesar that remains the ultimate political thriller

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Dadie Rylands, the late English lecturer at the University of Cambridge, once expressed the opinion that King Lear was unquestionably the Bard’s greatest work, and Hamlet and Othello weren’t far behind. Who am I to disagree with such a distinguished Shakespearean scholar? However, I put it to you that Shakespeare wasn’t just a magnificent poet and playwright, but also the greatest storyteller of them all. Allow me to put my case.

If you had been living in Cheapside in 1599, and wanted to spend a night at the theatre, you could have pitched up at the Globe, handed over a groat and joined the groundlings in the open air, while the posh people (nothing changes) possibly including Queen Elizabeth I, would have been sitting in the boxes behind you, all waiting in anticipation to see the Lord Chamberlain’s Men led by Richard Burbage give us his Mark Antony.

Now I feel sure we all would have marvelled at the verse, been moved by the oratory, but most of all I would suggest we would have been spellbound by a tale of power, revenge and vaunted ambition, as we waited breathlessly for the story to unfold, and unlike modern theatregoers, we would have had no idea how it was going to end.

To be fair, Lear, Hamlet and Othello also have pretty good endings, but it is Julius Caesar that remains the ultimate political thriller. Caesar (Margaret Thatcher), Brutus (Douglas Hurd), Cassius (Michael Heseltine) and Mark Antony (Cecil Parkinson); I wanted to play Mark Antony, but at school was cast as Flavius, a role I continued to play throughout my political career.

However, if like me, you are not a Shakespeare scholar but one of nature’s groundlings, you can put my theory to the test, as I did last year when my wife and I visited Stratford-upon-Avon to see the RSC’s production of Titus Andronicus, a play neither of us had seen before. During the interval I asked Mary how she thought it would end.

“I don’t know,” she said, “but I have a feeling they’re all going to die, and it will be very bloody.”

She turned out to be right, but there was still a twist in the tale that neither of us had anticipated, which convinced me that Shakespeare was not only the greatest playwright and poet of his age, but also a master of dramatic narrative.

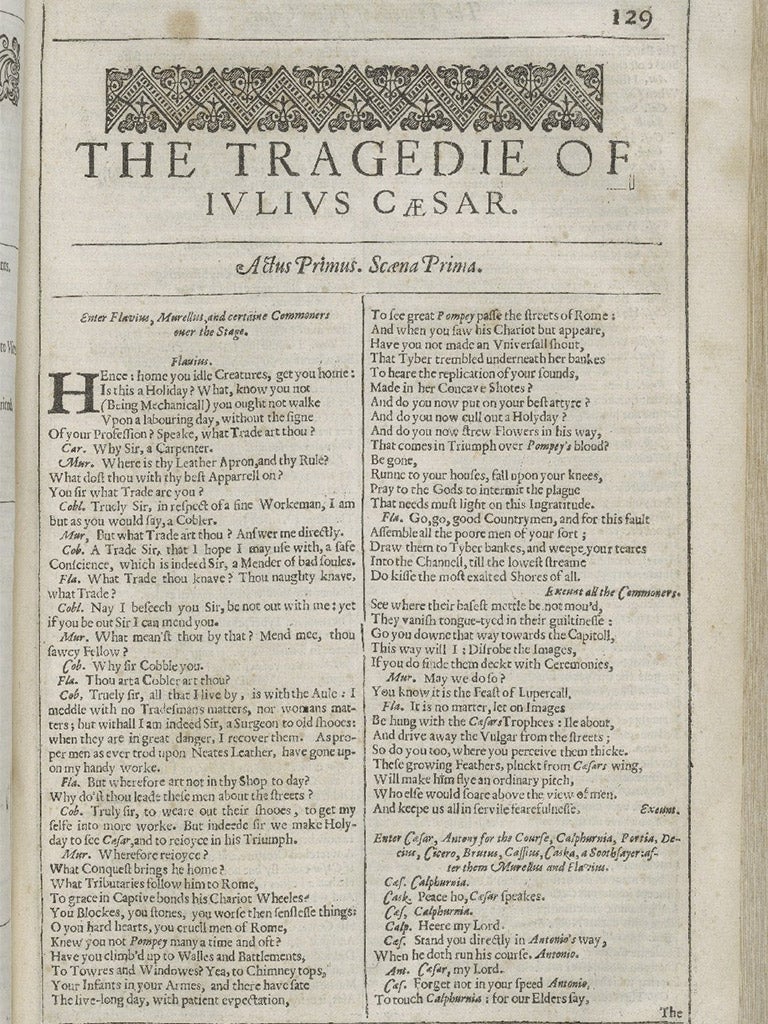

Dadie Rylands went on to express the view that great storytelling demands a beginning, a middle and an end. How’s this for a beginning:

Hence! home, you idle creatures get you home:

Is this a holiday? what! know you not,

Being mechanical, you ought not walk

Upon a labouring day without the sign

Of your profession? Speak, what trade art thou?

And a middle:

Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears;

I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him.

The evil that men do lives after them;

The good is oft interred with their bones;

So let it be with Caesar.

And one of the greatest endings ever written:

This was the noblest Roman of them all:

All the conspirators save only he

Did that they did in envy of great Caesar;

He only, in a general honest thought

And common good to all, made one of them.

His life was gentle, and the elements

So mix’d in him that Nature might stand up

And say to all the world ‘This was a man!’

Four hundred years after his death, and he’s still the greatest storyteller of them all.

Shakepeare at a glance: Julius Caesar

Plot

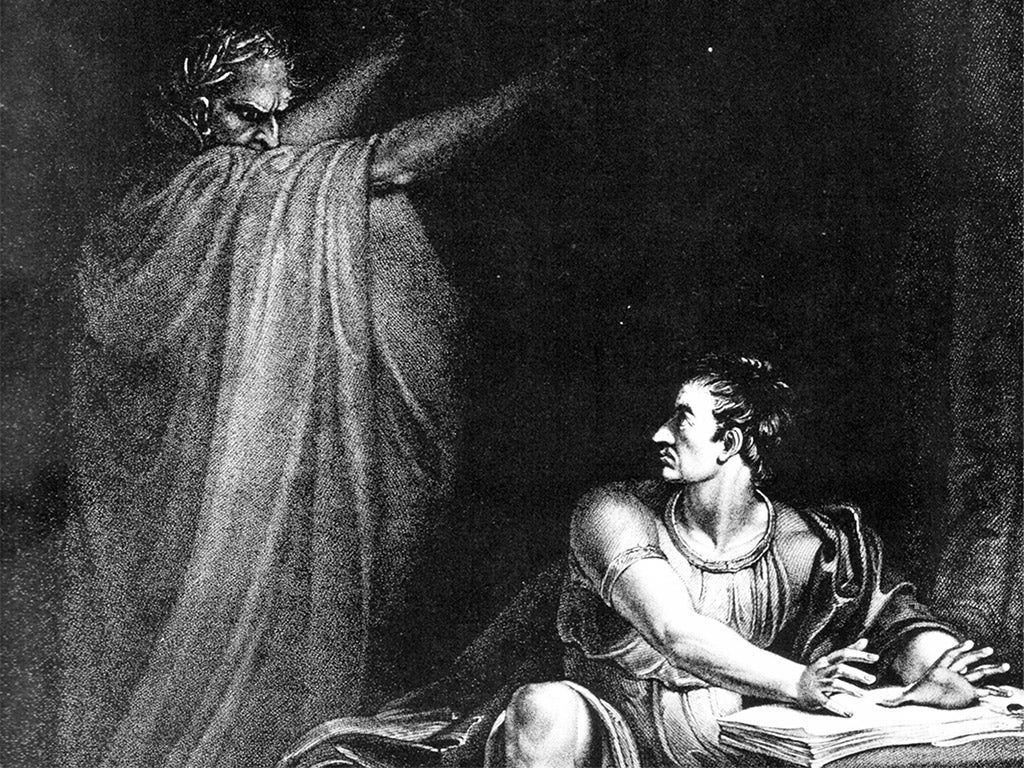

As Rome’s commoners celebrate Julius Caesar’s triumphant return from battle, Cassius persuades Brutus to join his plot to murder him. The senators fear that Caesar wants to make himself king. A soothsayer warns him to “beware the Ides of March”. In due course, the conspirators stab him. “Et tu, Brute,” says the dying Caesar. Brutus persuades mourners it was the right thing to do. Mark Antony persuades them to change their mind. Cue war, the Battle of Philippi, multiple suicides and the (temporary) ascendancy of Mark Antony and Caesar’s adopted son, Octavius.

Themes

Doom foretold; betrayal; the tension between public and private duty. The key character is not Julius Caesar but Brutus, who has four times as many lines. But is he the villain – or the hero? That is the question.

Background

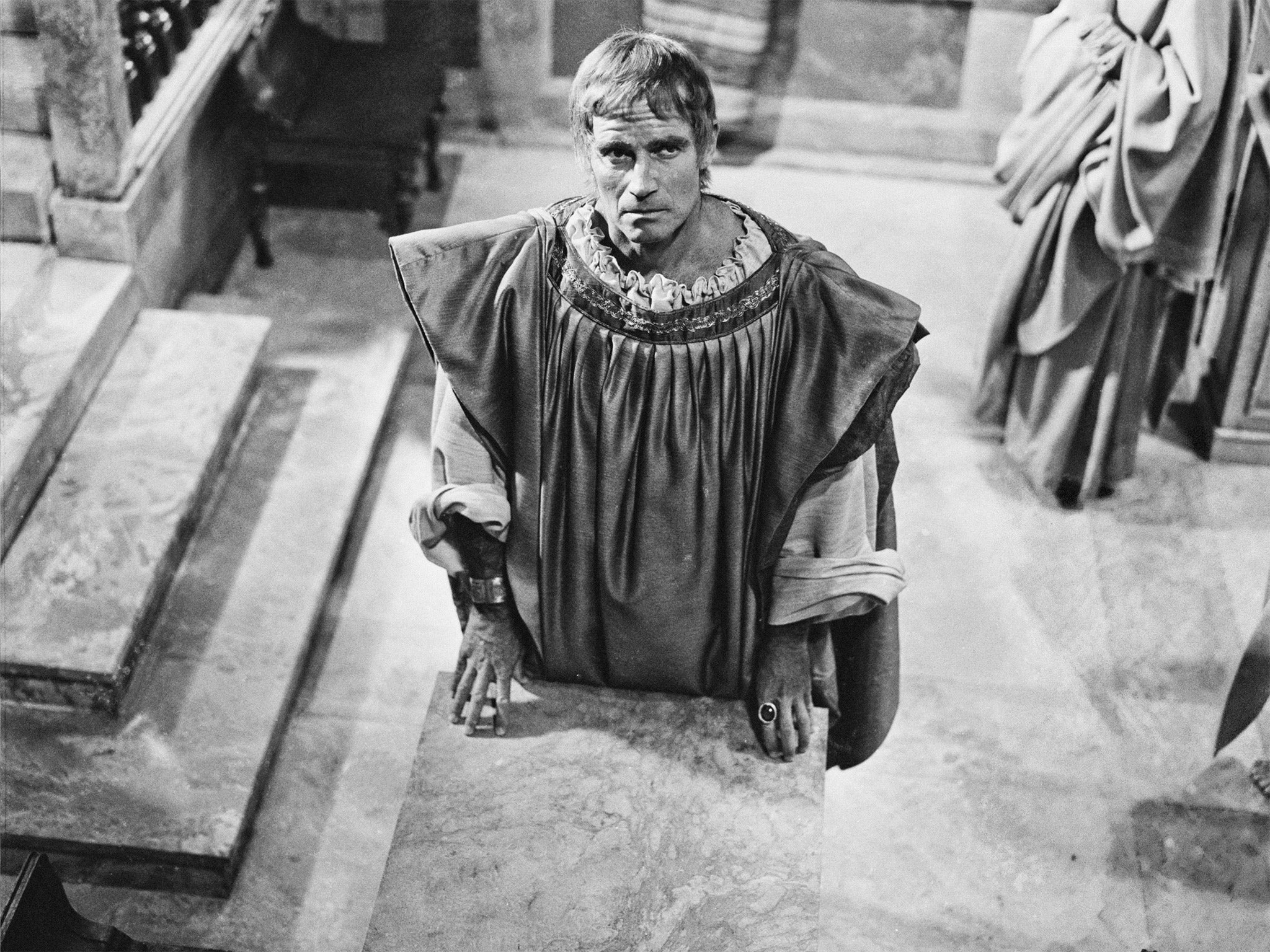

Probably written around 1599 and performed at the Globe. In an 1864 production in New York’s Winter Garden Theatre, Edwin Wilkes Booth played the part of Brutus to such acclaim that his brother, John, was consumed by jealousy and vowed to surpass Edwin’s fame. John later murdered Abraham Lincoln. Film adaptations include Joseph L Mankiewicz’s (1953, with Marlon Brando and John Gielgud) and Stuart Burge’s (1970, with John Gielgud and Charlton Heston). Gielgud played Cassius in the former and Caesar in the latter.

Key characters

Brutus: the “noblest Roman of them all”, torn between private feelings and patriotic duty.

Mark Antony: subtle, ruthless politician and spellbinding orator.

Cassius: coldly ambitious conspirator.

Top lines

“Beware the ides of March.” A soothsayer warns Caesar of his doom, Act 1 Scene 2.

“Let me have men about me that are fat… Yon Cassius has a lean and hungry look.” Caesar fears Cassius’s ambition, Act 1 Scene 2.

“Et tu, Brute? Then fall, Caesar.”

Caesar’s last words. Act 3 Scene 1.

“Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears…” Mark Antony prepares to turn the mob against the conspirators. Act 3 Scene 2.

“Caesar, now be still, I kill’d not thee with half so good a will.” Brutus’s dying words – expressing his sorrow at his part in his friend’s murder. Act 5 Scene 5.

“This was the noblest Roman of them all. All the conspirators save only he did that they did in envy of great Caesar.” Mark Antony on Brutus, Act 5 Scene 5.

Luke Barber

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments