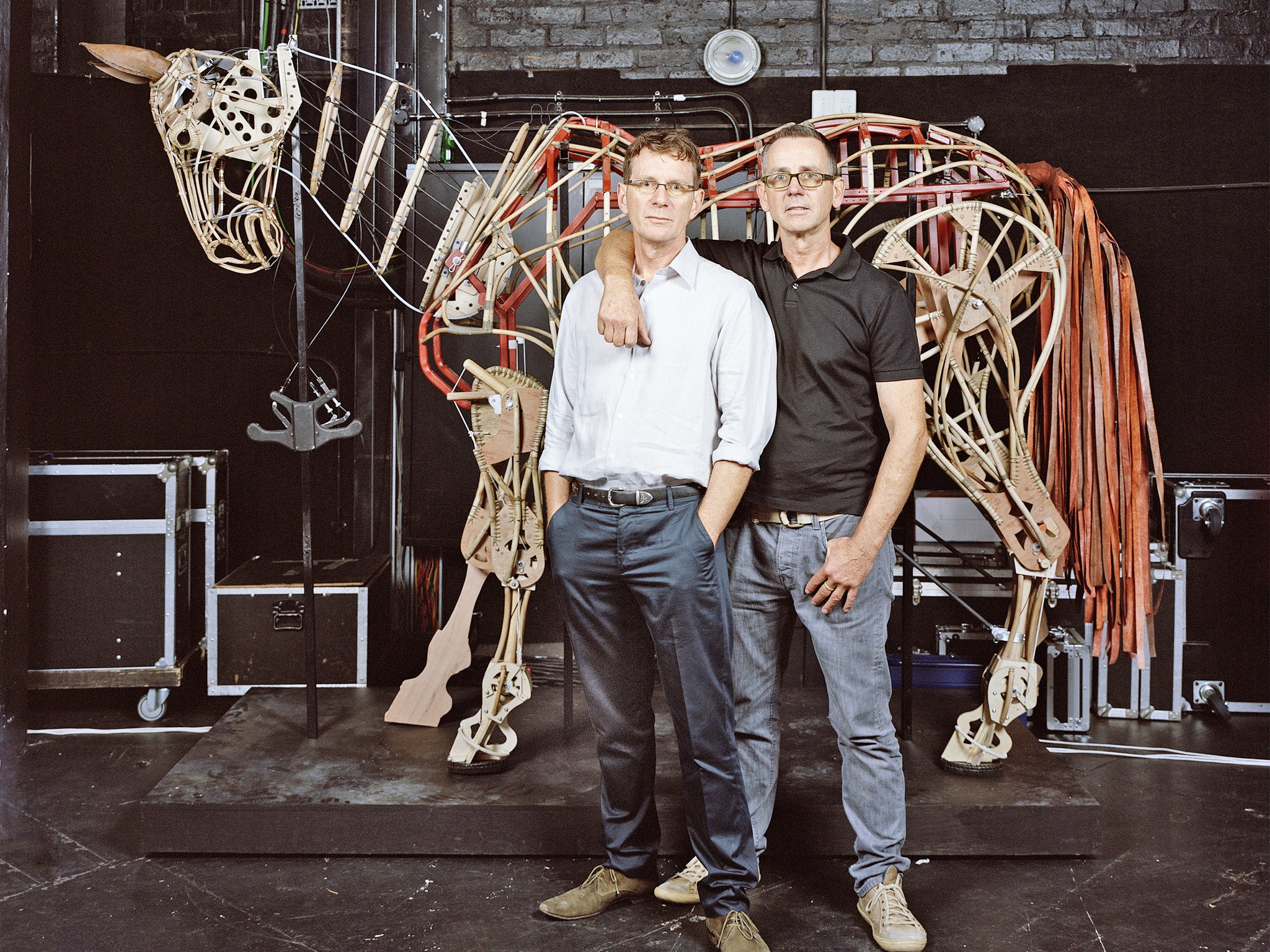

Genius puppeteers of The War Horse relive their South African roots in new London handspring production

Long before they created Joey, the equine hero of ‘War Horse’, Adrian Kohler and Basil Jones used puppets to tell the stories of their native South Africa. On the eve of the London revival of ‘Ubu and the Truth Commission’, Boyd Tonkin meets the pair pulling the strings

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In early October, as spring carpets the Cape Peninsula with a rainbow of wildflowers, Southern Right whales and Great White sharks glide beneath the wind-whipped waters of False Bay. Although I set eyes on neither legendary beast during my stay in Cape Town’s seaside suburbia, I do watch the outsize Cape fur seals as they haul themselves out of the sea like wheezy middle-aged swimmers and cadge for leftovers at the fish market in the village of Kalk Bay.

Around the harbour, a resilient community of so-called “coloured” fishing families – famous for their stalwart resistance to the ethnic cleansing of the Group Areas Act during South Africa’s apartheid regime – now coexists with artisan bakeries, seafood cafés and bohemian boutiques. And just up the hill from the waterfront, I visit the spot where another fabulous animal was born. In the wedge-shaped studio of a handsome house with panoramic ocean views, which Adrian Kohler and Basil Jones built 16 years ago, amid a workspace crowded with tools, sketches and half-finished puppets, and heavy with the resinous aromas of the woodworker’s shop, Joey first saw the light of day.

Since the founders of the Handspring Puppet Company first devised an equine hero for director Tom Morris at the National Theatre in 2007, War Horse and its expressive puppets has been seen by almost three million people in London; seven million around the world. The adaptation of Michael Morpurgo’s novel about a boy and his horse, Joey, in the inferno of the First World War has earned the NT more than £13m.

Yet when he first invited Handspring to make puppets, Morris told Kohler: “This isn’t a commercial show, Adrian.” A worried Nick Hytner (the then director of theatre) demanded cuts. “Suddenly the play leapt into focus,” Jones recalls. Then, Nick Ormerod, of the Cheek by Jowl company, hazarded a prediction, saying “‘I’ve been in theatre 25 years and I may be wrong, but I think you’ve got a massive hit on your hands.’ It was only then that we contemplated for the first time that it was going to be a success.”

Kohler and Jones, respectively the artistic director and executive producer of Handspring, have recently worked on the Chinese production of War Horse in Beijing. There, reports Jones as we talk while the daylight fades over the surf, the Great War may mean little, “but they’re completely in love with a horse and a war – any war”. Chinese audiences shared, adds Kohler, “that plunging of people into a dark and desperate place – and they survive. You are allowed to believe that you understand the horse’s emotions. That’s an unusual experience; theatrically: it gives you something that maybe you haven’t seen before.”

Jones and Kohler have been partners, personal and professional, for more than 40 years. Kohler is the puppeteer of genius and backstage master craftsman; Jones the visionary producer-entrepreneur. They met at art school and, in the early days of Handspring, toured children’s shows around South Africa from a truck with four bunks, until a state of emergency in 1985 turned schoolyards into war zones. In Johannesburg, they lived in a “resistance community”, plunged into the avant-garde theatre scene, joined forces with artist William Kentridge, and began to mount multimedia puppet-shows for grown-ups. In their first adult production, Episodes of an Easter Rising, a black activist takes refuge on a remote farm with two elderly women. We grasp that the women “had to leave town because of their love,” says Jones. “It emotionally fitted with Adrian and I, because that was what we understood as well.”

Three decades on, this marriage – in every sense, legal included – continues to bear fruit. But can they separate dramatic and domestic life? Jones laughs. “We try not to discuss work in bed.” Yet “It is a kind of a passion, an obsession. I say to Adrian: ‘30 years with no weekends! That’s been our lives.’ We do it because we do love it. We are workaholics.” Still, the house is designed so that doors mark thresholds between life and art. The puppets know their place – just about.

As productions multiplied around the world, so the home workshop in Kalk Bay gave way to a factory employing 28 craftspeople on an industrial estate in the nearby township of Capricorn. Now, as War Horse has reached a plateau, they have closed the plant and let it out. “What we miss,” says Jones, “is the camaraderie of the factory. And the tremendous pride of the artisanship that happened there. We saw fantastic development in kids who often were taking their first job out of school, from cane benders to expert constructors.”

In War Horse, argues Jones, “What we’re presenting has never been on stage before… a thinking, feeling animal’s life”. He says that, with Joey, “People are seeing a fully sentient and emotional animal. I think that we are the first company ever to do that… I know it’s hubris, but no one has contradicted me yet.” Beneath the nuanced articulations of their puppets lies the Handspring principle that “Movement is thought. That’s our most provocative assertion.”

This month, in London, British audiences will have the chance to sample one of the 17 productions that made the company’s name before Joey cantered in triumph across the planet. Directed and conceived by Kentridge, and written by Jane Taylor, Ubu and the Truth Commission premiered at the Market Theatre in Johannesburg in 1997, during the stormy springtime of Nelson Mandela’s “rainbow nation”.

The play took shape even as South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was still hearing testimonies from some of the countless thousands who suffered “gross violations of human rights” under the apartheid regime – and appeals for amnesty from a minority of the perpetrators. As puppetry, animation and graphics combine with live performance, Ubu also enlists the grotesquely comic anti-heroes of the French playwright Alfred Jarry. Here, Jarry’s Pa and Ma Ubu – a boorish, trailer-trash version of the Macbeths – become an apartheid-era policeman and his complicit wife. Harrowing accounts of torture, brutality and murder taken from the TRC records counterpoint the Ubus’ farcical and outrageous efforts to excuse their lives and views.

For Kohler, “the absurdist or surreal nature of the Ubu plays was a good way to capture in theatrical terms the absurd quality of the late-apartheid state”. Yet they worried that the victims of that state might think that they aimed to exploit the horrors revealed by the TRC. “How can you use these painful stories if they’re not your stories?” Kohler reflects. “How can you perform them as an actor?” Again, Handspring’s puppetry adds a unique ingredient to the mix on stage. “If the puppets speak the words, perhaps this is sufficiently removed from the actors. The puppet has a kind of neutrality.”

After the commission began its work in 1996, “It suddenly became an enormous opportunity to listen to our own stories in South Africa,” says Jones. “The phenomenon of the TRC here was intense. It was on television every day, and at the end on the week on Sunday there was a summary.” After more than 21,000 depositions, 2,000 public testimonies by victims, and more than 7,000 pleas for amnesty from acknowledged persecutors, torturers or killers, South Africa’s carnival of confession came to end when the chair, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, submitted his report in 1998. “The truth can be, and often is, divisive,” Tutu wrote. He warned that “True reconciliation is not easy, and it is not cheap”.

The TRC left a troublesome legacy. Many victims and their families received little or nothing of the modest restitution money promised. Many state criminals, including those in high places, got off scot-free. Complaints came, and come, from every side. Radical campaigns such as the Khulumani Support Group denounce it as largely a charade and – in every sense – a whitewash. The rich in South Africa stayed rich and the poor– still mostly black – if anything got poorer. From another quarter, vehement critics of the ruling ANC such as historian R W (Bill) Johnson castigate the process as “in every sense deeply flawed”, with a “wrong model” and a “historically indefensible” report.

In South Africa today, it can seem as if no one has a good word to say for the TRC. When I talk to another Kalk Bay resident, writer Mark Gevisser, he argues that “There’s unfinished business to the Truth Commission, and that is rearing its head in all sorts of very uncomfortable ways right now.” The movement to discredit “the Mandela reconciliation project” works on two fronts, he says. On the one hand, a “radical poor people’s position” says that “things are as bad if not worse”, 21 years after liberation. On the other, some young black intellectuals – vocal in the campus-based campaign Rhodes Must Fall – maintain that “Mandela was actually a sell-out. And that a deal was done in the mid-1990s which meant that everything stays the way it is for whites. There’s some truth to that. But both those positions are somewhat ahistorical, because they don’t grapple with what was clearly at stake in the early 1990s, and how close this country was to absolutely ruinous civil war – to real, blood-on-the-streets civil war. The deal that was made was to prevent that.”

In the inner-city Cape Town district of Salt River, I meet the anti-corruption and freedom-of-information researcher Hennie van Vuuren. His Open Secrets campaign nestles within a warren of radical NGOs in Community House – hallowed ground for anti-apartheid activists, as a focus of trade-union resistance during the struggles now commemorated in vivid murals on its walls. Van Vuuren lays stress on the “economic crimes” of apartheid – especially corrupt defence procurement in sanctions-busting deals with overseas corporations. The TRC “asked questions about this, but it never fully investigated how the money was spent, who the weapons were bought from, who were the international network of people who assisted the apartheid network and – importantly – who profited from the process.” Many fat cats strolled, unchallenged, between racist junta and rainbow nation. “It’s understandable that there must be accommodation for elites within the new system,” says Vuuren, but not “when it comes at the expense of truth, and at the expense of justice”.

Jones accepts that “almost a majority of South Africans these days” would say that the Commission was “a waste of time or a failure. I deeply and sincerely don’t believe that.” For him, anyone who dismisses the TRC “doesn’t understand what a precious trove of stories, good and bad, came out of it… Yes, ours was a very imperfect event. But it had wonderful leadership, with Desmond Tutu.” As for the four metre-long shelf of testimonies –purgatorial, cathartic, redemptive – “They are there forever: it’s so precious.” China, Handspring’s most recent conquest, had no such reckoning with the crimes and tragedies of its Cultural Revolution. It needs one, he believes.

Ubu and the Truth Commission arrives in London at a moment when the outside world, which during the Mandela era only paid attention to the bright side of the new South Africa, now tends to focus on the dark alone. With some reason: last week, the latest crime figures grabbed headlines, with 17,805 murders in 2014/15 (49 per day) – a homicide rate more than six times the global average.

Jones always thought, when liberation came, that “We would have bumpy ride for a century and we shouldn’t be surprised that we have big highs and big lows.” Kohler reflects that “We miss the euphoria of the Mandela years but also know in hindsight that it was a little too good to be true. You cannot change 300 years of oppression and expect it to be right overnight.”

The master puppeteers do make a difference. Their Handspring Trust nurtures theatre skills both in townships and in the rural community of Barrydale. There, in the Little Karoo east of Cape Town, many people can trace their ancestry to the Khoisan – South Africa’s aboriginal people. Every year, Kohler and Jones support a parade on the “Day of Reconciliation” in December, when a pair of their own giant puppets leads a pageant of symbolic unity. “Although apartheid ended 20 years ago,” reports Kohler, “these towns are still divided.” This time, their sixth year, a new grandstand will accommodate spectators – paid for through War Horse-inspired prints. Joey still has a spring in his step.

At the University of the Western Cape, Professor Premesh Lalu is both a Handspring board member and a long-standing champion of its work. The company, he thinks, has through productions such as Ubu shifted the terms of the debate about democratic transformation in South Africa away from law and politics alone and into the arts. “The TRC was a courageous project,” Professor Lalu says, “but at the same time it got stuck in the narrative of ‘transitional justice’. Now it must be reopened for new audiences.” Handspring has helped to achieve exactly that. “It’s not only reassessing the past. It’s asking us to think about the future.”

It turns out, though, that the puppeteers may be plotting more than revivals of their backlist. Much as he enjoys working in his Kalk Bay studio again, Kohler admits that “We miss the excitement, the terror, and – dare one say it – the love” of a show-in-progress. Just now, Jones reveals, “We might have to expand again. There is a project brewing.” He confides that “It’s still under wraps, but we are able to say that it’s something that would start in China, and we would hope to work with some of the puppeteers we met in Beijing.” So look east for the next Handspring epic. “When we’re building a new show, and the juices are really cooking, that’s when life feels best,” says Kohler. “If the politics are going askew in the country, you don’t have to think about it.”

The Print Room presents ‘Ubu and the Truth Commission’ at the Coronet, Notting Hill Gate, London W11, from tomorrow until 7 November. Box Office: 020 3642 660

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments