What do the scholars of the Shakespeare Institute actually do?

Nobody lives and breathes the Bard quite like the scholars of the Shakespeare Institute in Stratford-upon-Avon. Thea Lenarduzzi pays them a visit

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A hush descends on the room as it awaits the results of a hotly anticipated ballot; and a middle-aged man in a black shirt and grey trousers steps up to the lectern to address the hundred or so people gathered in front of him. He clears his throat. Someone drops a notepad. A shoe squeaks against the polished parquet floor. Beneath the hall's dark oak gables, the tension mounts.

Let America keep its gaudy primaries; this is Stratford-upon-Avon, and Dr Martin Wiggins, senior lecturer and fellow of the University of Birmingham's Shakespeare Institute, is about to reveal the names of five people who will each take a place in the Bard's birthday procession around the town next month.

Wiggins, who is 55, is joined at the front by an "ultra-glamorous assistant", Professor Ewan Fernie, one of the institute's newer recruits, headhunted in 2011 ("Though 'headhunted' might sound unusually contemporary in the context," he concedes). Every inch the modern Shakespearean, in leather jacket, jeans, and a Renaissance-inspired goatee, Fernie, who is 44, plucks pieces of paper from glass bowls and reads names aloud to the accompaniment of whoops and cheers, conjuring images of FA Cup draws and small-town tombolas.

The audience – a hotchpotch of scholars and members of the public – is right to be excited. This year's celebration will be the grandest yet, marking 400 years since the playwright's death in the parish on 23 April (also his estimated date of birth, in 1564). There will be concerts at the Barbican, a new poem by the Poet Laureate, and the first performance in more than 200 years of David Garrick's > all-singing, all-dancing Ode to Shakespeare, with readings by the actor Samuel West broadcast live on Radio 3.

And the Shakespeare Institute is at the heart of it all, feeding an eclectic, hydra-like body of events, including a major art exhibition (at Compton Verney gallery in Warwickshire); the British Film Institute's Indian Shakespeare on Screen season (featuring director Vishal Bhardwaj, "the Indian Spielberg"); and the long-awaited unveiling, just down the road, of The Other Place, a 200-seat studio theatre, that originally opened in 1974 and has been undergoing renovation.

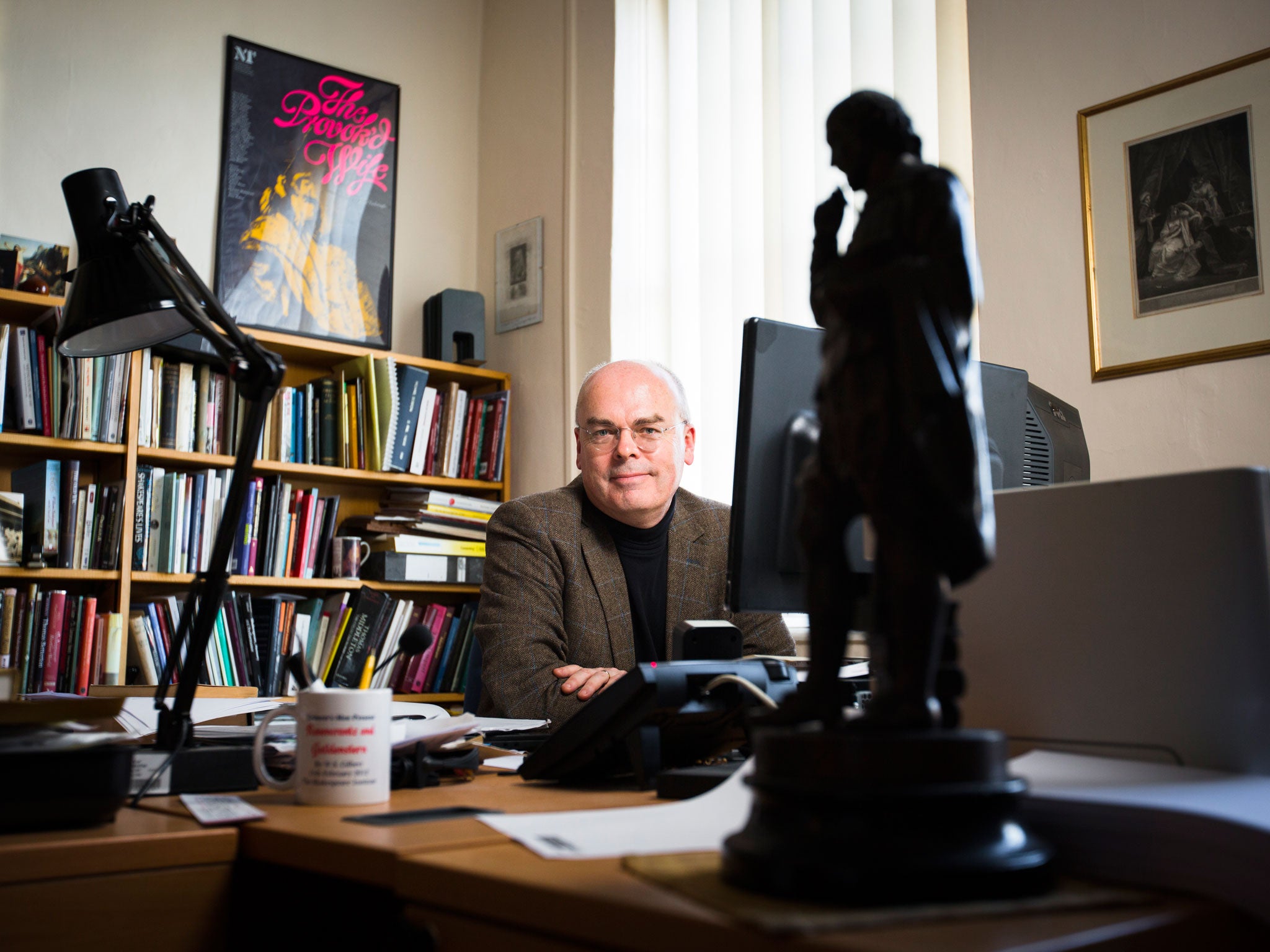

Not to mention the World Shakespeare Congress in July – a week-long programme split between Stratford and London – which, as Professor Michael Dobson, director of the institute (or, in his words, "theatre-goer and failed actor"), explains, presents the "wonderful logistical challenge of getting 800 academics on buses, on time". It's a real worry, he half jokes, in his sun-drenched office at Mason Croft, the 18th-century townhouse where the institute is headquartered. "But that's one of the great things about my job: I'm perpetually doing things for which I am absolutely not trained. I get the most extraordinary emails. Just the other day I was asked how one might go about setting the sonnets to Brazilian drumming."

Dobson, who's 55, leans forward holding up his hands in a gesture somewhere between that of a saintly supplicant and one carrying a loaded tea tray: "People see the word Shakespeare by your name and presume you must have the answer." Which is fair enough, really, because – between the institute's seven professors and fellows, two full-time librarians, associated academics and honorary fellows – every trust with the word Shakespeare in it can be traced to this unimposing terrace on Church Street, about halfway between the house where the Bard was born and the church where he is buried.

No other body in the world represents quite such a concentration of Shakespeare thinking as this institute. Nowhere else will you find a group of people who live and breathe Shakespeare to such an all-consuming extent. Former directors include esteemed academics such as Professors Kate McLuskie and Russell Jackson (among other things, textual adviser to Kenneth Branagh, who is an honorary fellow), and Professor Stanley Wells, who retired in 1998, but stayed nearby, becoming president and then honorary president of the Birthplace Trust (Shakespeare's first home, where three of his earliest printed texts are held).

Now 86, Wells shows no signs of swapping the stage for the stalls. "He still has an office at the trust, in which he can be found writing most of the time when he isn't lecturing somewhere," says Dobson. For many, Wells embodies the kind of generous and benevolent elder statesman who might have made all the difference in one of Shakespeare's tragedies – one might compare him to the grey-haired Lafeu in All's Well That Ends Well, an unwavering proponent of honour and charity. He still gives at least one guest class every academic year and is often consulted by the institute's students about their research projects.

The Shakespeare Institute was founded 65 years ago by the theatre historian Allardyce Nicoll, with the intention of creating a "Shakespeare university" for students and the public, which would draw together the resources of the local Royal Shakespeare Company theatre and the libraries at the University of Birmingham and the Birthplace Trust. Thankfully, Mason Croft had already been bequeathed to the townspeople in 1924, "for the promotion of science, literature and music" by resident eccentric Marie Corelli, a popular novelist and failed performer. (The latter may have something to do with her caveat that "all persons connected with the stage" be excluded, a condition happily not met today.) Nicoll secured finance from a local businessman, an heir to the McVitie's biscuit empire – because the institute, then as now, received no direct government funding.

"Since the beginning it's been a question of public campaigning," says Dobson. "I spend a lot of time worrying over budgets rather than texts," he adds, absentmindedly stroking a statuette just in reach ("sold to my father as Shakespeare, although it turned out to be the Italian poet Tasso – who's got better hair"). The institute is part of the University of Birmingham, he explains, so it doesn't have trustees or an independent budget. "I get wheeled out to show potential donors to the university how valuable and expensive the institute is, but if they do cough up, their donations go into a central university fund."

A purpose-built research library came in 1996, the result of a campaign led by Judi Dench, who cut the ribbon. The modern building juts out of the back of the old house into a garden now carpeted with lilac crocuses. They do well to seize their chance – in the summer, these lawns will be trampled by the Institute Players, whose outdoor performances of the works of Shakespeare, as well as other Renaissance playwrights, never fail to draw crowds.

The library now holds a collection of about 60,000 volumes (including 3,000 early 17th-century printed and rare books), newspaper clippings, manuscripts and recordings. "When you add our library to those at the university and the Birthplace Trust," explains Karin Brown, who has managed the library for 10 years, "we're the second biggest Shakespeare library in the world." (The Folger in Washington DC comes top – "because they've got money!" she says.)

For Brown, who's 45, with brown curls falling around her shoulders, the performance archive is "one of our greatest treasures". In a cramped attic room are box after box of annotated film scripts, assistant directors' prompt books, and notebooks. "We have an early draft of Baz Luhrmann's Romeo + Juliet, and scripts from Michael Powell's never- realised film of The Tempest." That project dates from the 1970s, and would have starred James Mason.

You might also browse – members of the public are granted access, too – scripts and storyboards for Branagh's 1996 film of Hamlet, which you could contrast with Samuel West's 2001 notebooks and theatre scripts for the same role. Between the unassuming covers of West's notebook are pasted cartoon clippings of Batman's Joker ("Don't get ee-ee-even, get mad!"), while his script is criss-crossed with insights. In Act 3, just before "To be, or not to be, that is the question", West has jotted in heavy pencil: "Answer the question! NEED" and "I can't carry on the play until I sort this out". There are plenty of expletives, too. "He uses the word 'fuck' a lot, which," says Brown with a wry smile, "shows the, um, passionate nature of his Hamlet."

"I want this to be the IMDB equivalent for performance," Brown explains, "with the whole thing digitised so that everyone can share it." But funding is scarce. And donations of a non-monetary sort remain essential. West and the actor Jasper Britton are "our great living contributors". Often, she adds, actors don't feel comfortable sharing the sort of soul-searching that goes into a role. "Normally we have to wait until they're dead to get that kind of access."

"We're all part of a community," Wiggins emphasises, sitting in an attic study lined with books. (A cake knife sits on top of a copy of Thomas Middleton in Context, "still waiting to be claimed" after his Christmas dinner with students). "There's a certain amount of…" Incubation? "Yes, but it's not a hothouse, and certainly not a sweat shop. This is the place where knowledge is made. That is our 'product'," he explains with the mischievous air of one all too aware of the increasing encroachment of business into academia.

Shakespeare, who rose to the top of London's thriving and potentially lucrative theatre scene, would surely have empathised. In those days, though, the "product" was drama, and there was a lot of it about. "It's simply not a case of one majestic river surrounded by mud," says Wiggins, whose research is concerned with the period from the Reformation to the Revolution – "about 110 years, which produced around 2,800 known plays, of which Shakespeare's work represents less than 2 per cent. A very rewarding 2 per cent, but 2 per cent nonetheless."

So how will Wiggins be marking Shakespeare's 400th? "Every year we perform the entire corpus of one person, and this year" – he pauses briefly – "we're doing Thomas Dekker," a lesser-known contemporary of Shakespeare, most of whose work has been lost. "Four hundred… it's just a number."

It's a sentiment that Dobson echoes – to a degree. "The 400 is important because of what it enables" – in short, a network of "gigs" around the world. "Weirdly, Shakespeare doesn't count as foreign in other countries. He was the writer you couldn't be seen to ban – so he belongs to everybody." And how does that shape the institute's remit? "We're an ideas lab, a database," and long- distance learning is an ever greater part of the day-to-day. Seminars are now live-streamed so that registered students can take part wherever they are.

Rather different, then, to the place that Wells found when he arrived as a student in 1958 – "the whole place was just crammed with books!" (To be fair, it still is.) It was during Wells's 10-year reign as director that the new library came about, as well as the creation of the chair of Shakespeare studies position.

Today, Wells and Dobson sit like bookends to the institute's work, past and present – the one clean-shaven, the other grizzly-bearded; both fans of the polo-neck, in black and off-white, respectively. As Wiggins says of the institute's own evolution, "different and yet the same".

Wells had popped in for the Thursday seminar, "the thrilling highlight of our week", announces Dobson. But now, back in the main hall, applause dispels any hint of irony. Ego, too, is left at the door and, as Fernie transitions from assistant ballotist to leading man ("Please help yourselves to the most off-putting handout ever produced"), esteemed former directors and high-flying scholars sit alongside students with pink hair and pensioners with blue rinses. In a lecture replete with quips, pop-culture references and even a tongue-twister ("Hegel-Garrick-Herrick"), Fernie extols the radical, inclusive "freshness" of the Bard's politics, celebrating his characters as proof of "the power in ourselves to be used". There is, after all, he adds, an established bond between Shakespeare and democratic revolutionaries; just down the road, at their Stratford HQ, the Suffragettes once hung a banner above the entrance reading "To Be or Not to Be" – what else?

And it does feel decidedly democratic, as we move on to questions from the audience (many being lecturers in their own right), and, finally, drift out for refreshments in Corelli's once-verdant winter-garden, now a simple common room. There's a cake sale to raise funds, one flapjack at a time, for the Players' summer performances. "I did say we were built on baked goods, didn't I?" says Dobson. It's democracy with a sweet slice of free-market capitalism, then. "Through efforts to high things", goes the institute's motto, and you could add to that Friar Laurence's advice to the young upstart Romeo: "Wisely and slow. They stumble that run fast."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments