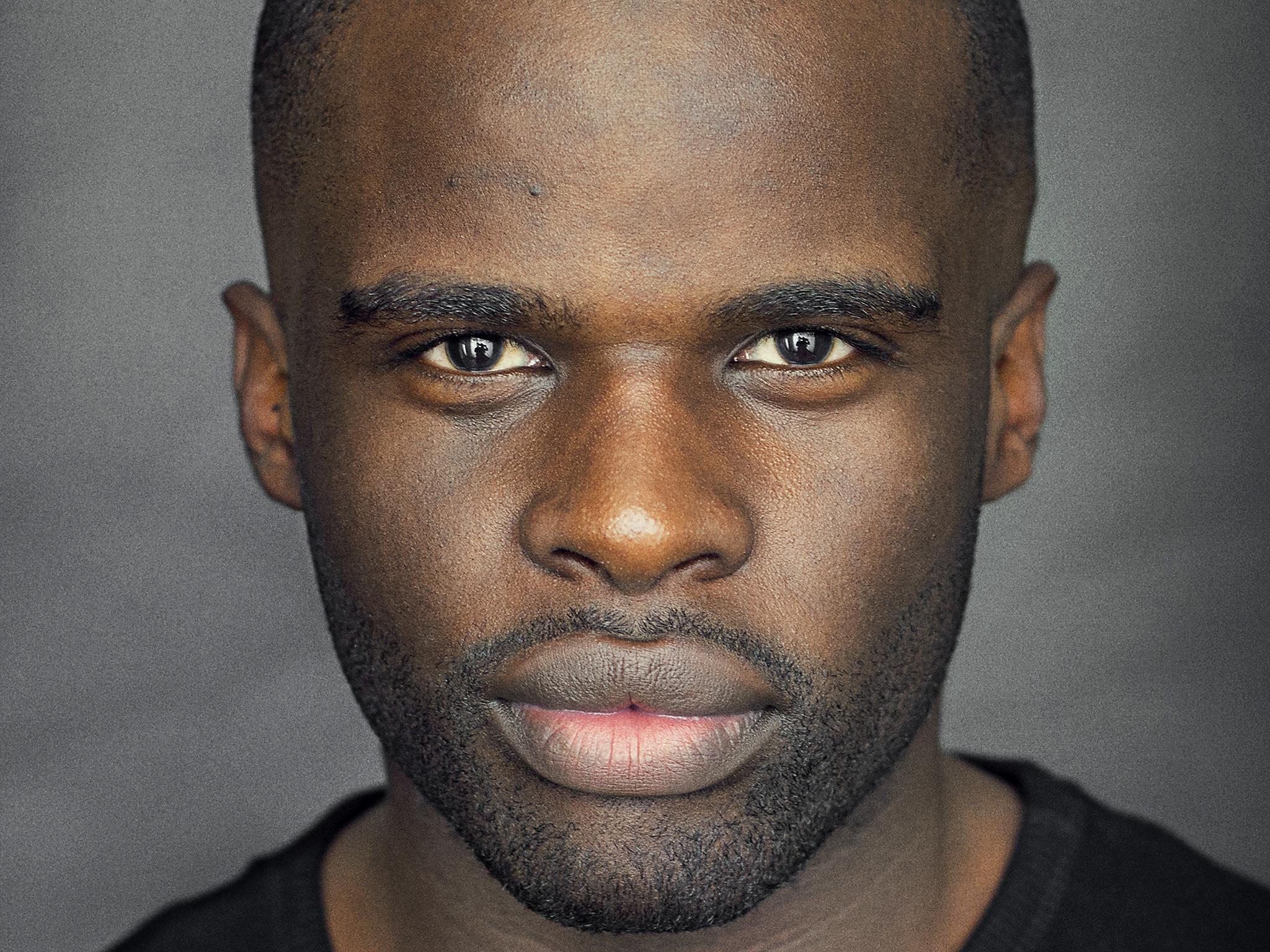

Urbain Hayo talks about black deaths in British police custody in his play: 'People think it’s an American issue but it’s not. We just don’t want to talk about it'

The actor, who goes under the stage name of Urban Wolf, has created 'Custody' based on real-life cases of police brutality and black deaths

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Urbain Hayo was 14 when he first got stopped and searched by the police. When the London riots exploded in 2011, following the police shooting of Mark Duggan, he wasn’t surprised.

“As a black kid from south London, I totally understood why they were rioting – it was because of the complexity of the relationships with the police,” he says. Now an actor going by the stage name Urban Wolf, the 25-year-old has just created his first play, Custody – alongside writer Tom Wainwright – looking at police brutality and black deaths in custody.

The play, which opens at Ovalhouse, tells a fictional story of a family struggling in the aftermath of the death of their son due to police force, and a subsequent cover-up by the police, a farcical investigation by the Independent Police Complaints Commission, and a failure to prosecute any of the officers involved.

Custody is based on research Hayo conducted into real-life cases, working with the charity Inquest and interviewing bereaved families. He’s passionate that this is a story that needs to be told – that while we are becoming used to hearing about racially-motivated police brutality in the US, and witnessing the swelling of the Black Lives Matter campaign, in the UK we bury our heads and pretend it just doesn’t happen here.

The initial spur for the show, however, was a desire to communicate his own fraught relationship, as a young black man, with the police. Hayo was a studious teenager, well-spoken and well-behaved: “I got good grades, I was a prefect at school, and I thought that would affect how people treated me – but with the police that obviously wasn’t the case.”

The first time he got stopped and searched, aged of 14, was traumatic. “The way [the police officers] went about it was very aggressive, they put their hands all over my body and I honestly felt violated. I felt so powerless, they didn’t treat with me respect and it ended up getting violent. Knowing that what it comes to the police, they already have a certain perception of me and what I am – that was devastating to me.”

Noticing that a lot of handwringing about the riots came from the political and middle classes professing not to understand the rage that bubbled over that summer, Hayo’s initial aim was to create a play offering an insight into the dialogue that black men have with the police. “You just won’t know what it’s like ’til someone has touched your body or treated you a certain way because of your colour, and your power is completely taken away.”

But during his research he watched a documentary, Injustice, made by activists Migrant Media in 2001. The incendiary film documents the struggles for justice of the families of victims who have died in police custody. The film – and, in particular, its suggestion of a deliberate cover-up by the establishment – shocked Hayo, and moved the focus of his own project to police custody deaths.

Some 147 black, Asian and ethnic minority (BAME) individuals have died in police custody in England and Wales since 1990, according to Inquest. As a disproportionate number of total deaths, the campaigning charity suggest that institutional racism has been a “contributory factor”. In that time, although nine unlawful killing verdicts have been returned at inquests into deaths involving the police, and one at a public inquiry, no police officers have been successfully prosecuted. In the last 30 years, there has not been a single prosecution for homicide for a death in custody.

“All these black people have died, but no-one speaks about it, the public doesn’t know,” suggests Hayo. “No police officer has been prosecuted ever, even when the evidence or the pathology has shown that brutal force was used. Black bodies, they don’t have value. I wanted to make theatre that tells those stories, to give those people a voice.”

One of the inspirations behind the wholly fictionalised story Custody tells was the case of Sean Rigg, who died in custody in Brixton police station in 2008. Suffering from schizophrenia, he was held in a prone restraint position by police before being arrested, and transported handcuffed and face-down to the station. Unwell when he was put into a cage there, he later died of heart failure. An initial IPCC investigation found no evidence of wrongdoing but, after dogged campaigns by his family, an inquest in 2012 concluded “unsuitable” force had contributed to his death.

A damning independent review of the IPCC revealed a catalogue of errors including failure to secure the crime scene, properly examine CCTV or carry out a robust analysis. Yet this September, the Crown Prosecution Service ruled out prosecuting any officers in relation to Rigg’s death.

For Hayo, the fact that, even in cases such as Rigg’s, the police have never been prosecuted is indicative of a “deep, deep rooted institutional racism” in this country.

He says: “Everyone is complicit, because if we don’t talk about it, how is it ever going to get changed?”

In telling an archetypal narrative of a family’s fight for justice, Hayo wants to not only stage black lives and give a voice to people not heard enough in British theatre, but also to get this story in front of white, middle class audiences.

“I do feel like there’s a reluctance in theatre in general to do these kinds of stories and I hope this will challenge that,” he says. “But I was also aware that I didn’t want to create a story that was alienating to white people. That’s why I wanted to work with a white writer, to make a story that draws everyone in.”

Hayo collaborated with Tom Wainwright for Custody. Hayo developed characters and scenarios, and Wainwright penned the final script. The hope is that Custody ends up being a piece of truth-speaking story-telling that audiences both black and white, personally familiar or seemingly untouched by issues of police brutality, can connect to.

“If we can work together, and he can come into my head to tell that story, then it becomes something that everyone can understand,” suggests Hayo. “I could have chosen to work with someone who has gone through that experience, but I wanted to choose somebody middle class and so far away from it, to push them to write from my experience in a genuine way. Hopefully that means other people for his background will be able to [relate to it] too.”

As the Black Lives Matter campaign in the US goes from strength to strength, the issue of police violence has certainly gained attention. But Hayo believes that, in the UK, we’re in denial about our own problems. “People think it’s an American issue but it’s not. We have a very polite culture – whatever makes us look ugly, we have to cover it up, we just don’t want to talk about it. People need to stop and look – there are things we’re ignoring and people are dying on a regular basis.”

While Hayo’s story goes far beyond his own experience, the show is rooted in his own personal anxiety in the face of the frankly shameful levels of racism that still exist within our society: “I don’t drive because I’m scared to be stopped by the police. I have to be careful how I walk. I have to be cautious, because I might die [if arrested]. As a black person living in 2017, that’s the reality of my life.”

'Custody' is at Ovalhouse theatre until 8 April

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments