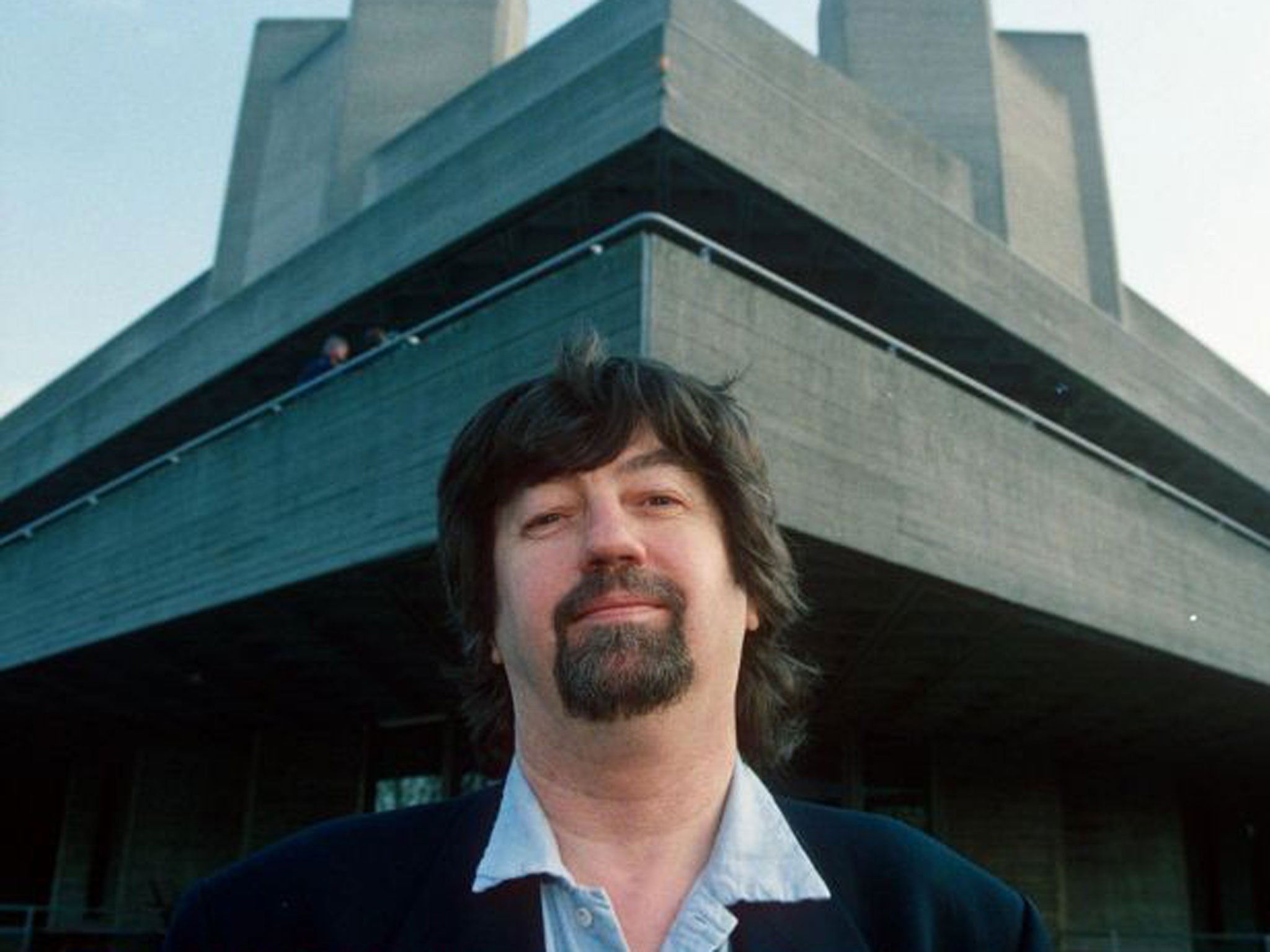

Trevor Nunn: My theatre of dreams

As the National Theatre celebrates its half-centenary, former artistic director Sir Trevor Nunn recounts the company's many achievements and transformations

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I have a letter from George Bernard Shaw. It is framed and hangs in my study, having been presented to me by a grateful board at the end of my period as director of the National Theatre. Shaw says, “The unanimous refusal of the English people to establish an English National Theatre must not discourage them. The Englishman is so modest on his own account that he never believes that anything English deserves to succeed, or can succeed, but he is tremendously credulous as to foreign possibilities.”

At the beginning of my professional theatre career (which is also celebrating its 50th anniversary), I was intensely aware of the establishment, in 1961, of the Royal Shakespeare Company, to perform in both Stratford and London a repertoire of plays ancient, modern and new, indigenous and foreign – not to mention the entire canon of the greatest dramatist who ever lived. The creator of the ensemble, avowedly seeking to achieve the status of the Moscow Art Theatre or the Berliner Ensemble, was the most phenomenal directorial impresario of our age, Peter Hall.

So, I confess, when I first heard talk of the imminent opening of a “National Theatre” to be housed at the Old Vic, I found the idea somewhat superfluous. I mean, we already had one. At that time, the RSC also presented its annual World Theatre Season, during which those aforementioned legendary companies, plus the Comédie-Française, the Greek Art Theatre, and groups from Japan, Africa, Eastern Europe and America showed their revelatory wares. It seemed that all the bases were loaded.

But Laurence Olivier was the most famous actor in the world, so of course it was right and destined that he alone should lead the expedition to find the theatrical Xanadu that Shaw so pined for.

The success of the project was immediate and spectacular, though it should be recorded that Olivier's National owed much to the English Stage Company, which was formed by George Devine at the Royal Court in 1956, and furnished Olivier with wonderful directors such as Lindsay Anderson, William Gaskill and John Dexter. And in terms of selecting repertoire, Kenneth Tynan, the famously pungent theatre critic of The Observer, became the power behind Olivier's glittering throne.

In coded acknowledgement that it was now subsidising two national theatre operations, the Arts Council decreed that the director of the National and the artistic director of the RSC must meet at least once a year to exchange their planning ideas, with strict instructions not to overlap, and never to duplicate.

When the National was still in its infancy (and when many people understandably thought that I was too), I became the artistic director of the RSC, and thus the person who had to negotiate with Olivier. Or should I say with “Larry”, as he insisted I call him? Since he addressed me as “Trev Boy”, the atmosphere was always convivial.

The Old Vic was nowhere near big enough to accommodate the offices and departments of the formidable new National, so temporary accommodation was set up in a Nissen hut in Aquinas Street close by – a surreal location for some pretty surreal conversations.

“You go first,” Larry commanded at our inaugural meeting. I ran through the Shakespeare season I was proposing, and then talked briefly about the new and neglected plays that the RSC was hoping to do at its then London base, the Aldwych Theatre. There was a pause as he looked intently at me and then, with the hint of a twinkle, he said: “You bastard!”

All notions of identity and primacy changed in 1976 with the move of the National from the Old Vic to its present home in Denys Lasdun's mighty three-auditorium complex on the South Bank. I believe that the only person in the country who could have visualised, rationalised and organised the perpetual output of the highest quality in this three ring circus was Peter Hall. The sine qua non. The guv'nor.

Over the ensuing decades, those of us who have run the National, opening up new areas of activity, new complexities of repertoire, and new densities of output, have all drawn on the blueprint so brilliantly invented and bravely accomplished by the first director of the building that we are all so proud of alongside Waterloo Bridge.

There were, as with every theatre company, successes and failures. There was good luck and bad. But the overall enterprise continued to thrive and amaze. The Richard Eyre years (1988-97) witnessed a further great leap forward in the programming's daring and identity. Especially during that time, the National presented searing national enquiries, including David Hare's “State of the Nation” trilogy. The excitement aroused by this new work was palpable. I felt it when I went to the National to direct Tom Stoppard's latest masterpiece Arcadia, and it was a privilege to be part of such a confident and buoyant enterprise.

But then, it was a regime I came to witness at first hand and at close quarters. For much of a year, I shadowed Richard, observing his extraordinary fleetness of foot in situations of every level of sensitivity. I had agreed to become his successor in the full knowledge that he was an impossibly hard act to follow – but I hadn't applied for the job. No secret was made of the fact that the powers that be had hoped either Stephen Daldry or Sam Mendes would baton-change with Richard; but both young candidates had burgeoning careers in Hollywood and had replied to soundings with a polite “maybe later”. So I was urged, as somebody with experience, to hold the fort and be a bridge to the future. I agreed to sign up for five years, but I took on the daunting task, thinking of it partly as an honour, yes, but mainly as a duty. At all events, it was clear that I was not being employed as a new broom.

By the time I was actually doing the job, it was the funding and subsidy issue that loomed largest. Margaret Thatcher's miserable insistence on standstill grants for all arts organizations meant that the Arts Council was disallowed from responding even to the rise in inflation, let alone from considering ambitious creative possibilities. So, in simple terms, it was ticket sales that largely paid for our productions, and therefore we were under pressure (as commercial theatres are) to be popular if we were not to dwindle.

On the wall in my office, I put up a collage by the contemporary artist David Mach, who delights in creating fantasy views of London landmarks, such as a Formula One Grand Prix race around Parliament Square. My Mach was of Lasdun's “Brutalist” National Theatre, but as nobody had ever seen it – all its balconies and terraces crowded with ecstatic partying play-goers, and in front of the river façade, a jostling throng being entertained by everything from fire-eaters to flamingoes. This fantastical image represented to me the unattainable ideal, a National Theatre which could be the entertainment destination of anybody and everybody, its demographic reach ever widening, its range of work fully extended to include the most intellectually demanding texts through to the most joyous ecstatic “events” and everything in between.

Knowing that whatever else I did, I had to keep the operation in the black (which even then involved raising millions of pounds a year in private funding and sponsorship), my attempt to stretch the meaning of a “National Theatre” was unavoidably limited and sporadic. At the end of my agreed time, during which we had won a cabinet full of awards, and knowing that our research had confirmed an appreciable expansion of our audience demographic, I could bear the necessity for caution no longer.

With some enviably energetic young talents at the National, I set up a season called Transformation, for which we reconfigured the Lyttelton to make a space in which we could do “events” created by innovators such as Deborah Warner and Matthew Bourne; and for which we also opened a new small theatre at the top of the building, presenting new plays by young writers, under the control of young directors. It was also a season for which I managed to establish a seat price of £12. It was a gesture, a hope; the building came vividly alive, the festival atmosphere was pervasive … but there were no flamingoes.

By then I had got Nicholas Hytner to come back to do productions at the National, and I was overjoyed when he became the front-runner in the succession race. In the 10 years since Nick took over from me in 2003, the dream has come true: the fire-eaters and the crowds are all there, and Mach's montage looks scarcely fantastical at all. The range of work has been dizzying and explosive and the popularity factor seems to have doubled, with the £10 Seasons, with National shows running triumphantly in the West End and on Broadway; and with the company now televising and filming its work (oh, how I tried), and broadcasting live to cinemas around the world. The National has also won the battle (one that I fought and lost when this brilliant proposal was first made) to be financially responsible for producing its own commercial transfers, ensuring that the profits come back into the National's creative coffers. There is still more than a year to run of Hytner's brilliant period at the helm, and knowing him, yet more fireworks will light up the South Bank.

I was similarly delighted that Rufus Norris, a young director whom I have long admired, has been named as Nick's successor. The current regime has topped all previous phases of the National's history. We often hear the dictum that in this country (and especially in the capital) we have the best theatre in the world. Rufus, I know, will continue to open up the building to all, and to surprise everybody with his vision of what is possible; he will do so in the knowledge that at this moment in time, the accolade of “best theatre in the world” belongs to the National Theatre all by itself. GBS would be speechless.

National treasures: the 20 shows that changed the world

By Paul Taylor, The Independent's chief theatre critic

1. Othello (1964)

Laurence Olivier's prodigious feat of transformation (see cover picture) electrified the majority (“He was the African continent” wrote one critic) and embarrassed others who felt it was an insensitive caricature of blackness. But it was a characteristically unforgettable and intrepid performance by the NT's founding artistic director.

2. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (1967)

Kenneth Tynan, the NT's first literary manager, championed Tom Stoppard's ingenious early play in which Shakespeare's bit players take centre stage as a Beckettian double act. The rest is history – a lot of it occurring at the National.

3. Long Day's Journey Into Night (1971)

It takes an actor of genius to reach right inside the soul of an actor who realises, too late, that he has betrayed his great gifts – as was evident from Olivier's stupendous portrayal of James Tyrone in Michael Blakemore's definitive production of the Eugene O'Neill classic.

4. The Misanthrope (1973)

Tony Harrison shifted the proceedings to 1966, replaced Louis XIV with Charles de Gaulle, and pulled off the rare accomplishment of a genuinely satisfying English version of Molière. Alec McCowen and Diana Rigg relished the dazzling wit and acerbity of the rhyming couplets.

5. No Man's Land (1975)

In Peter Hall's meticulous production of this mysterious, bleak and very funny Harold Pinter play, Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud were a slyly brilliant double act as the moneyed dipsomaniac litterateur and the seedy failed poet who may be one another's alter ego.

6. Guys and Dolls (Olivier, 1982)

This was the first ever staging of a musical at the National, and Richard Eyre's elating production, with Bob Hoskins and Julia McKenzie, confounded the sceptics by being both a critical triumph and a box-office smash.

7. The Mysteries (Cottesloe, 1985)

Bill Bryden's exhilarating promenade production of these medieval plays – a 12-hour journey from the Creation to the Last Judgement – as adapted by Tony Harrison with a wonderfully gritty grasp of their working class origins and communal spirit.

8. A View From the Bridge (Cottesloe, 1987)

Michael Gambon gave a superlative performance – hefty yet full of trapped sensitivity – as the sexually confused Brooklyn longshoreman Eddie Carbone, in a production by Alan Ayckbourn that sounded the tragic depths of Arthur Miller's play.

9. An Inspector Calls (Lyttleton, 1992)

10. Angels in America (Cottesloe, 1993)

Tony Kushner's brilliant two-part “Gay Fantasia on National Themes” threw away the play-writing rule book, and took on the Aids crisis, the resurgence of the right-wing in the US, Mormons and millennial anxieties. Flamboyant and ferociously intelligent.

11. The Hare Trilogy (Olivier, 1993)

David Hare's ambitious and penetrating trilogy – on the church, the law and the Labour Party – was one of the peaks of Richard Eyre's tenure and remains the supreme example of the National Theatre examining the state of the nation.

12. Arcadia (Lyttelton, 1994)

Trevor Nunn's production beautifully brought out the haunting playfulness and poignancy of Stoppard's masterpiece, which ponders the irreversibility of time even as it shuttles ironically between the early 19th and late 20th centuries.

13. Copenhagen (Cottesloe, 1998)

Michael Frayn applied the uncertainty principle to Heisenberg's own inscrutable visit to fellow scientist Niels Bohr in Copenhagen in 1941. Set in an afterlife of never-ending conjecture, the play is a profound meditation on the mysteries of human motivation.

14. Blue/Orange (Cottesloe, 2000)

A young black man with possible schizophrenia is caught between warring psychiatrists in Joe Penhall's taut, challengingly ambiguous three-hander about race and the diagnosis of mental illness. Roger Michell staged this instant classic on a set that resembled a boxing ring.

15. The Far Side of the Moon (Lyttelton, 2001)

The Canadian auteur Robert Lepage rightly won the Evening Standard Best Play Award for this one-man show in which the rivalry between two brothers and the competition between the US and the USSR in the space race became magical, haunting metaphors for each other.

16. Henry V (Olivier, 2003)

Nicholas Hytner kicked off his regime with a searingly sceptical modern-dress Henry V, starring Adrian Lester, which implied an analogy with another leader who went to war on legally dubious grounds. Shakespeare's works have been provocative plays for today during Hytner's tenure.

17. The History Boys (Olivier, 2004)

Richard Griffiths was magnificent as Hector, the maverick teacher who has better things to pass on than exam tips in Alan Bennett's wonderfully funny and wise play about education and its purpose. The boys (including Dominic Cooper and James Corden) went on to fame and fortune.

18. War Horse (Olivier, 2007)

19. The White Guard (Lyttelton, 2010)

Thanks to the director Howard Davies, the National has a proud record with the Russian repertory and nowhere was his mastery of mood and of a teeming ensemble clearer than in his superb staging of Mikhail Bulgakov's great tragicomedy set in the turmoil of the post-Revolutionary civil war.

20. London Road (Cottesloe, 2011; then transferred to the Olivier)

It bodes well for the future of the National that its director-designate Rufus Norris nurtured this genuinely groundbreaking musical which, instead of lyrics, used the verbatim testimony of a community recovering from the murders of local sex-workers. An ear-opening experience.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments