Theatre's love affair with ménages à trois

As Noël Coward’s Design for Living returns to the stage in a landmark production, Paul Taylor explores the simmering tensions of the ménage à trois and its irresistible allure for dramatists

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Groucho Marx came up with one of the best gags about ménages à trois. In Animal Crackers, he ogles a couple of starlets and quips: "We three would make an ideal couple. Pardon me while I have a strange interlude". He was referring to the epic 1928 drama Strange Interlude by Eugene O'Neill, in which the heroine is protractedly torn between two men. The joke, though, would work even better as a comment on Design for Living, the Noël Coward comedy which premiered in New York five years later, starring the same actress, Lynn Fontanne.

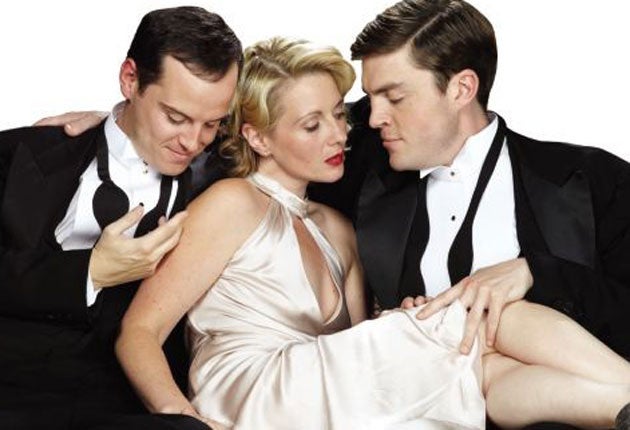

Coward's arty MMF trio (a painter, dramatist, and interior decorator) love one another equally and, after exhausting the various à deux permutations, wind up in what Gilda's ousted husband denounces as "a disgusting three-sided erotic hotch-potch". With a major revival, directed by Anthony Page, now in previews at the Old Vic, it's a good time to take stock of the sheer audacity of Coward's comedy and its geometric, unashamedly logical solution to the problems of jealousy, coupling, and bisexual passion.

A successful ménage à trois could be seen as both anti-social and anti-dramatic – a symbol of defiant self-sufficiency that defuses external threat by bisexually incorporating it. It's as though at the end of The Merchant of Venice, Portia were to neutralise any lingering challenge from Antonio, the man who risked his life for love of her new husband, by inviting him to share their marital bed at Belmont. So it follows that playwrights have tended to find more creative potential in triangles where the bisexuality simmers unconsummated, expressed through a shared surrogate, or where it's the fantasy of an imagination haunted by the potential torture of double exclusion.

Harold Pinter is a master of this territory. In his reverse-winding play Betrayal, it becomes increasingly clear that adultery augmented the bond between the cuckold and cuckolder. The last scene reveals that the seven-year affair began with the husband's vertiginous choice of turning a blind eye when he catches his best friend making a drunken pass at his wife in the marital bedroom. By electing to let the moment pass, Robert betrays all three of them, establishing a triangle in which he and Jerry seem often to be more concerned with one another than with Emma. In Old Times, the film-maker Deeley is threatened by the advent of the seductive Kate, who once shared a flat with his wife, Anna. As he and the guest swap competitive, unreliable accounts of their intimacy with her, the play becomes a devastating, dream-like study of the husband's retrospective jealousy and of his abject need to insinuate himself into a past where, to invoke the title of the film that becomes a bone of contention, he fears he may have been the Odd Man Out.

A key influence on these plays was James Joyce's Exiles (completed in 1915), which Pinter directed in a revelatory revival in 1970. "You are so strong that you attract me through her," the journalist Robert tells his boyhood best friend, Richard Rowan, a writer who, after nine years in Rome, has returned to Dublin with Bertha, his common-law spouse. A wishful authorial self-projection, Richard resolves to take radical measures against his masochistic, Joyce-like compulsion both to encourage his wife's admirers and endure torments of vindictive resentment. Refusing to guide, support or dissuade Bertha through Robert's attempted seduction of her (though expecting her to give him a blow-by-blow account), he claims that "It is not in the darkness of belief that I desire you, but in restless, living, wounding doubt." Part of the fascination of the play, though, lies in the elusiveness of Richard's motives for this creepy, cat-and-mouse experiment in marital freedom. In a way that prefigures the latent bisexuality in later 20th-century drama, it's insinuated that Bertha is partly a proxy for the mutual attraction of the two males.

"The actual facts are so simple," declares Leo to Gilda in Design for Living. "I love you. You love me. You love Otto. I love Otto. Otto loves you. Otto loves me. There now! Start to unravel from there." There's a hilariously crude variant of this in Pinter's 1993 play Moonlight, where the civil servant protagonist marvels, on his death-bed, at the rum symmetry whereby his mistress became his wife's lover. "Think of the wonder of it," he barks at his better half, "I betrayed you with your girlfriend, she betrayed you with your husband and she betrayed her own husband – and me – with you. She broke every record in sight. She was a genius and a great fuck."

Both these statements have the amusing and rare virtue of suggesting that bisexuality, on which ménages à trois depend, can be viewed as a positive asset, a handy knack like double-jointedness or ambidexterity. Often, in triangular drama, it comes across as the non-choice of narcissistic evasion – brilliantly so in the case of Mike Bartlett's Cock (2009), where the Ben Whishaw character, who has discovered his straight side during a break from his long-term gay relationship, torments his rival partners with a protracted display of introspective shilly-shallying, which makes Hamlet look like a demon of headlong decisiveness. Alternatively, bisexuality can find itself presented as inherently duplicitous as in the portrait of the eponymous, cockily AC/DC thug in Entertaining Mr Sloane. Joe Orton arranges a blackly comic comeuppance for the amoral youth when Kath and Ed, the gruesome siblings whose father he has kicked to death, blackmail him into taking turns at being their sex-slave in six-month shifts. Like a perverted twist on the myth of Proserpina, this fate (and the grotesque triangle it creates) is a pointed, mocking punishment for the desire to have it both ways at once.

Coward's three-cornered solution in Design for Living is notable, by contrast, for its shameless impunity and defiance. This extends to the title, though its manifesto-like ring is evidently ironic, intended to apply only to these bohemian butterflies and not to mankind in general. Coward wrote the play as a vehicle for himself and his friends, Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne. In his autobiography, he reveals that early on in their careers the three had made a pact that once all of them were "stars of sufficient magnitude... then, poised upon that enviable plane of achievement, we would meet and act triumphantly." The journey to the creation of Design for Living thus intriguingly mirrors the route of Gilda, Otto and Leo in the establishment of their ménage à trois, since, though they are ambivalent about success, it's not until they have gone off and separately achieved it that they can unite in a fully-fledged threesome.

Like any modern revival of the piece, Page's production, which stars Tom Burke, Lisa Dillon and Andrew Scott, will have had to decide how explicit to make the sexual and homoerotic subtext. Abandoned by Rachel Weisz's sizzling Gilda, Paul Rhys and Clive Owen ended their drunk scene by falling hungrily into one another's arms rather than (as the text suggests) "sobbing hopelessly on each other's shoulders" when they appeared in Sean Mathias's steamy version at the Donmar 15 years ago. Purists were even more incensed by Joe Mantello's 2001 Broadway production, complaining that Alan Cumming had turned Otto into an unambiguously screaming queen.

And how ambivalent should we feel about the central trio? To what degree do we laugh at them as well as with them? There's a famous photograph from the first production of Coward and his co-stars intertwined on a sofa and abandoned in gleeful mirth at the climactic exit of Gilda's affronted art-dealer husband, the aptly named Ernest. Coward, who had his reproving, Puritan side, tried to hedge his bets a bit here, arguing that he preferred to think that they were principally laughing at themselves. Given that the author's stage directions require Ernest to fall over a package of canvases during his huffy departure, this is disingenuous. No, that celebrated image suggests an exclusive, irresponsible trinity closing ranks against respectable bourgeois convention in an eroticised mutual admiration society. If Groucho Marx's gag had the measure of Strange Interlude, Bert Lahr and Ray Bolger captured the snobbery of Design for Living in a song from a contemporary skit: "We're living in the smart upper sets/ Let other lovers sing their duets/ Duets are made by the bourgeoisie – oh/ But only God can make a trio". The blithe triumph of Coward's triangular menage stems from the fact that it is also, manifestly, an égoisme à trois.

' Design for Living', Old Vic, London SE1 ( Oldvictheatre.com), to 27 November

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments