The world's first Samuel Beckett festival: Well worth waiting for

The festival unexpectedly revealed the playwright's lighter side

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In Enniskillen, Northern Ireland, last Bank Holiday weekend, you could have yourself a "Beckett" haircut, buy an Endgame sandwich (ham-and-clove filling), watch a game of rugby contesting the Samuel Beckett Muckball Cup – the playwright's desiccated Krapp calls the Earth "a muckball" – and hear Antonia Fraser talk about one of the handsomest men she ever met.

The occasion was the first Enniskillen International Beckett Festival in the town where the young budding writer and outstanding sportsman went to school in the early 1920s – the same school, Portora Royal, as Oscar Wilde attended 50 years earlier.

This obsession with sport, which Beckett maintained all his life, certainly explains the athleticism paradoxically required to perform his notoriously static and downbeat plays.

"Bend it like Beckett" was indeed the weekend's theme as games were played all over town – except, unfortunately, the Didi and Gogo cricket match between artists and critics ("sewer rat, cretin, critic" exclaim the insult-trading tramps in Waiting for Godot), which was cancelled due to a waterlogged pitch – and festival-goers rushed like blue-arsed flies between venues for scraps of pith and pessimism.

In Portora's school hall, a woman's mouth, that of the actress Lisa Dwan, jabbered elastically and unforgettably for 10 minutes in Not I. Later, on the other side of town, avant-garde director Robert Wilson delivered a beautifully stylish and balletic Krapp's Last Tape, peeling his banana with studied intensity and gawping at his own past like a shock-haired amalgam of Buster Keaton and Dr Caligari.

For it was the brilliant and original notion of the Happy Days weekend ("Oh, this is going to be another happy day," witters Winnie, buried to her waist in rubble) that Beckett, whose characters rage against the dying of the light in a monochrome vacuum, or hellhole, should be revealed as an artist tinged with myriad lighter touches, a playful humourist ("the greatest Irish humourist since Swift" proclaimed Beckett biographer James Knowlson), music-lover, serial polygamist, an unrivalled ace punster, influential visual and technical innovator.

People turned out in droves to hear Will Self, face like a concave loofah, say that he was far more influenced by Joyce than by Beckett; and Lady Antonia define the happiest of marriages (that of Harold Pinter and herself) as one containing the jolliest of disagreements. Edna O'Brien, who gave an elegant and revealing introductory talk, floated fragrantly through the events accompanied by her son, the distinguished writer and film-maker Carlo Gebler, who lives locally.

In some ways, this was an anti-festival, just as Beckett's highly theatrical plays are anti-plays, his limpid, Modernist writing also anti-Modernist. How surprising was it that David Soul, of all people, should suddenly appear, virtually unannounced, in the chapel at Portora School to read the prose piece, "Fizzle 2", confessing that, while the rest of his body closed down, he was still throwing the javelin at 40, striking Usain Bolt's victory sign of a sculptured trajectory?

And in a darkened square room behind the Catholic cathedral (which is right across the road from the Protestant church), the audience sat in rocking chairs listening to the radio play All That Fall, one of Beckett's funniest pieces, and one of the few specifically located around Dublin.

This play, which concerns a trip to the local station and the discovery of a child's body on the line, was first broadcast by the BBC in the same year, 1957, as the railway was discontinued to Enniskillen, an example of the weird serendipity behind so much of the festival.

Its founder and artistic director, Seán Doran, a Derry man who has produced major festivals in Australia, resigned from running the English National Opera in London 10 years ago when the board insisted he should produce Kismet (which turned out disastrously) instead of Merce Cunningham dancing in Morton Feldman's one-act opera Neither – with a text by Samuel Beckett.

It's a cliché to say that Beckett is the ultimate writer of light and dark, but I'd never experienced the truth of this so intensely before as in this All That Fall (a play soon to be staged with visible actors – Eileen Atkins and Michael Gambon – in London); or indeed as at a remarkable installation by the conceptual artist Joseph Kosuth, Texts (Waiting for–) for Nothing, in which long strips of illuminated words can only be read at a certain distance and which, close up, look like braille in darkened relief against a black wall.

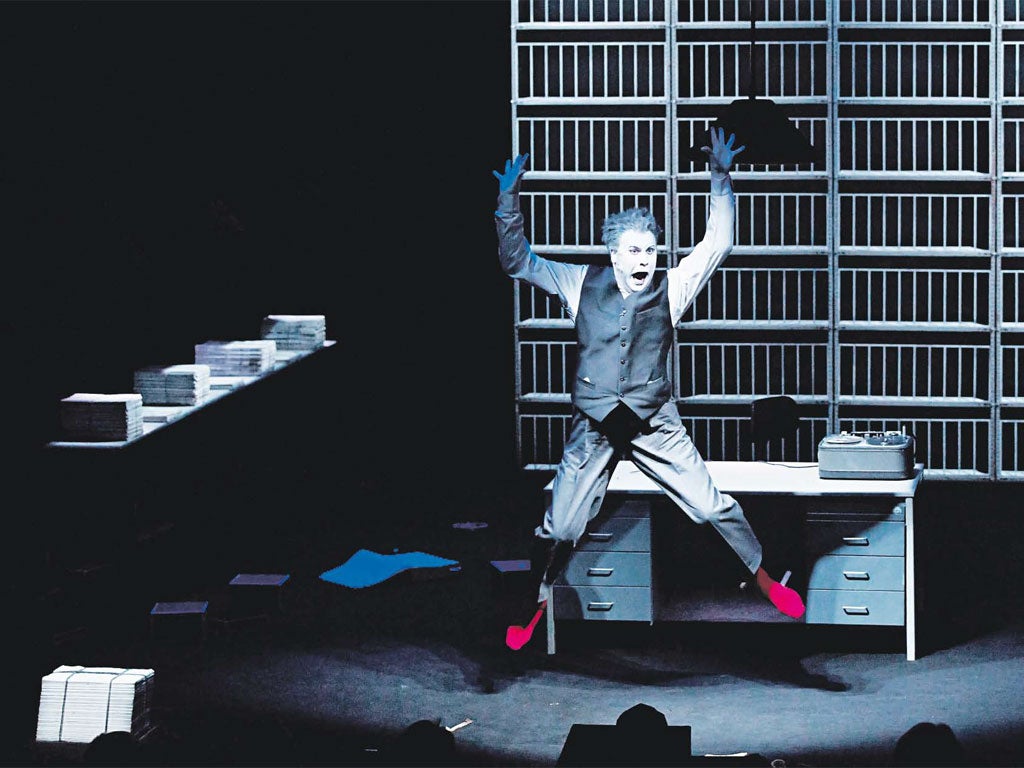

Robert Wilson's Krapp's Last Tape, in its European premiere, was entirely conceived in black and white and grey. It opened with the most tremendous thunder clap, an explosion, followed by a torrential rain burst indicated by fluvial stair rods running down the white spines of a virtual library.

One of the most haunting of conventional Krapps, John Hurt, could be discerned on video in a forest of 35mm travelling celluloid in film-maker Atom Egoyan's Steenbeckett (2002), an outrageous variation, while, across the corridor, Krapp's office gathered dust and memorabilia, and an overpowering sense of loneliness and desolation.

Beckett's working title for Krapp's Last Tape was "The Magee Monologue" in honour of the legendary Irish actor for whom he was writing it, Patrick Magee, so it was only just, in a witty piece of programming, that one of the country's greatest folk fiddlers, Tommy Peoples, should tell us about his life and his music while listening to his old recordings in a show called The Peoples Monologue.

Back in the school hall, the issue of whether Beckett was a French or Irish writer was deliciously skipped by a French puppeteer performing the wordless Act without Words I.

Out of town on the Castle Coole estate, the servants' quarters were invaded by Beckettian ghosts, the strained voices of actors Barry McGovern and Natasha Parry emerging from pots and pans while a bizarre mash-up of extracts from the novel Molloy and The Pirates of Penzance emanated from a phonograph in the hallway.

In the grand yard at Coole stood a gleaming stainless steel tree by Antony Gormley, which will be weathered in the notoriously wet Enniskillen climate before returning in 2014 as the scenic totem in an Aboriginal Australian-Irish co-production of Beckett's most famous play, Waiting for Godot. Sounds like more kangaroo sport, sport.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments