A Streetcar Named Desire at 75: Blanche, Stanley, and the Tennessee Williams play that still haunts us

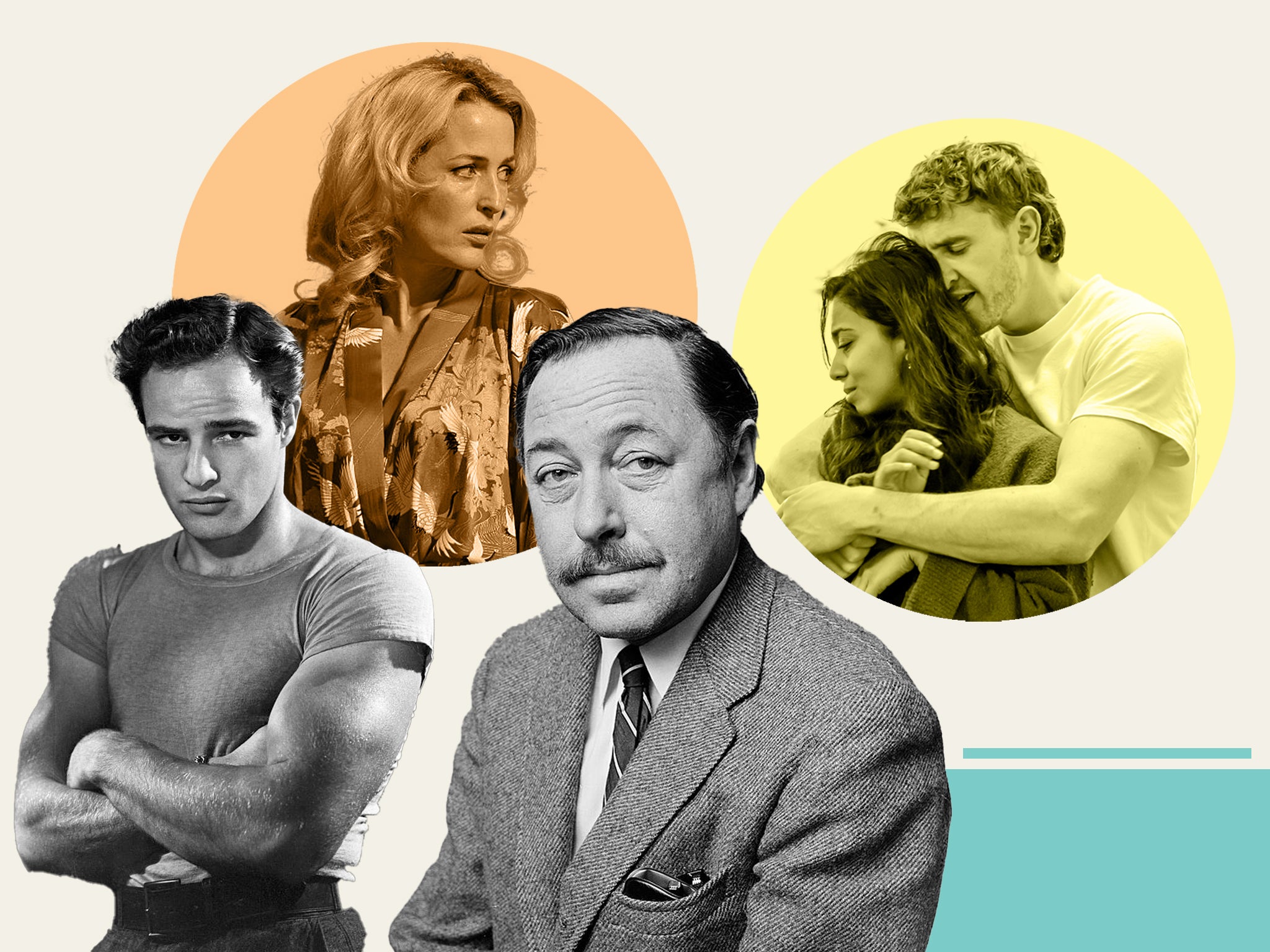

As Paul Mescal takes on the role first made famous by Marlon Brando, Holly Williams looks at the star-studded history of ‘Streetcar’, a play full of parts coveted by big name actors

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.To star in Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire is a dream for many actors – but the play comes at a price. “It tipped me into madness,” admitted Vivien Leigh. She had been doggedly determined to play the part of the self-deluding, fading Southern belle Blanche DuBois, but her own struggles with bipolar disorder were exacerbated when she took on the role in 1949, directed on stage by husband Laurence Olivier. Legend has it that she could even be found wandering London’s red-light district alone at night after shows, talking to prostitutes, finding an affinity between them and Blanche’s own “more pathetic promiscuity”.

Williams’s play – which is celebrating its 75th anniversary this month – follows Blanche’s unravelling. But it is not just her story: Streetcar contains a triangle of complex characters, whose failure to be honest with one another gives the play its tragic momentum. Having lost her family home, Blanche travels to New Orleans to stay with her sister, Stella, who lives in a shabby apartment with her brutish but charismatic husband Stanley Kowalski. While the snobbish Blanche weaves glamorous stories about her life, Stanley sees straight through her. Blanche and Stanley are both attracted to and repulsed by each other, and he becomes determined to break her, exposing her sexually promiscuous past – and leaving the pregnant Stella torn between her sister and her husband.

Leigh is not the only actress to have been deeply affected by the part of Blanche. When Gillian Anderson played her in 2014, she said that she “felt like all the layers of my skin had come off. You need to immerse yourself in a mental state to make the character truthful on stage ... There were moments when I felt I was hanging on to reality by a thread.” In Anderson’s Olivier-nominated performance at the Young Vic, this vulnerability poured off the stage as we watched Blanche’s harrowing descent from seemingly polished glamour to near-total collapse.

Streetcar first opened on Broadway in December 1947, and 75 years on, it is still showing no sign of fading in its appeal. Indeed, it’s about to get a birthday outing, with a new production opening at the Almeida this month, starring Normal People’s Paul Mescal as Stanley. The part of Blanche, due to be played by Lydia Wilson until health issues forced her to quit the show, will be taken up by last-minute stand-in Patsy Ferran – who won an Olivier for her performance in Summer and Smoke, another Tennessee Williams play also directed by Rebecca Frecknall. Bafta nominee Anjana Vasan is Frecknall’s Stella.

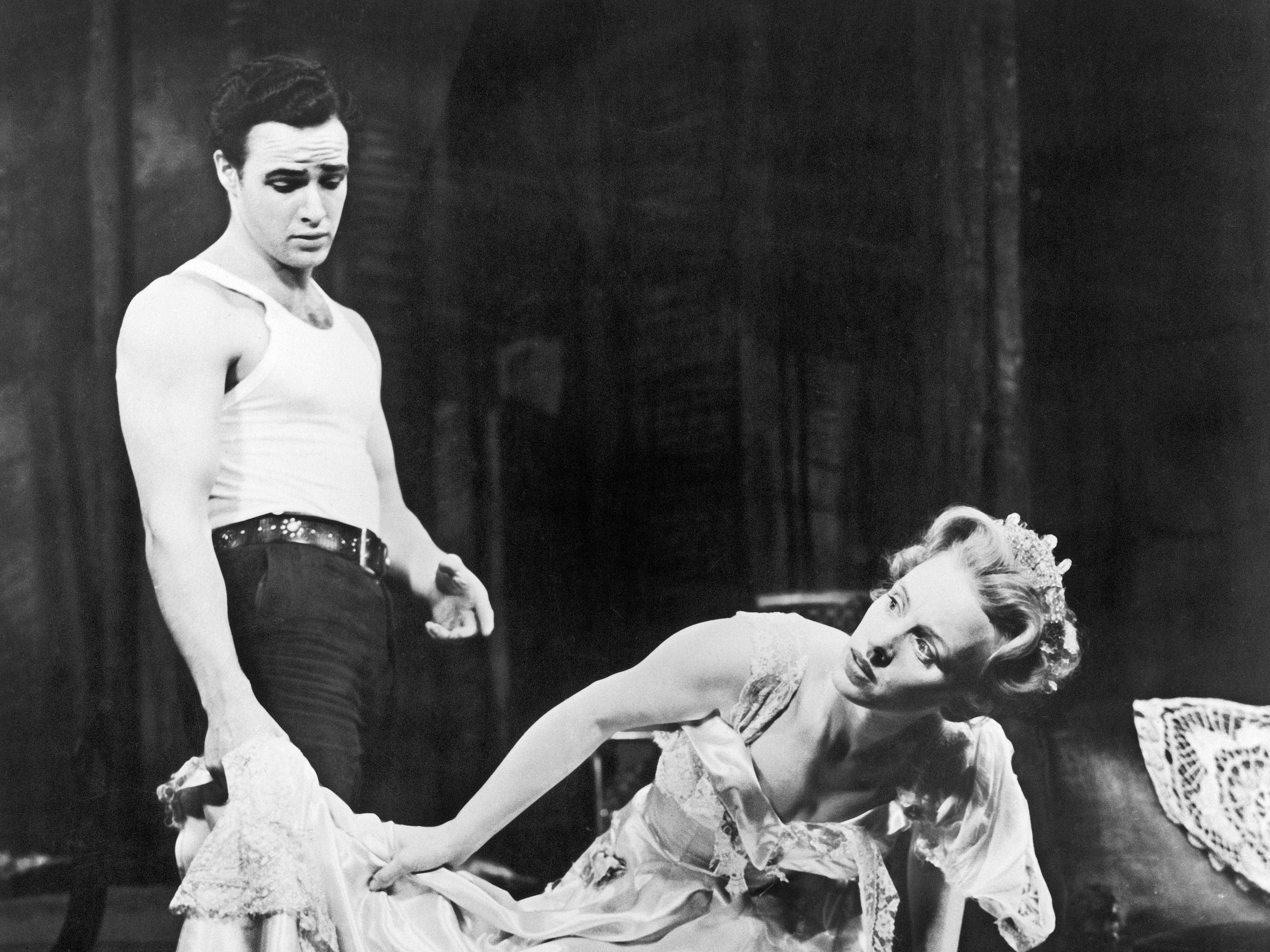

Throughout its celebrated history, Streetcar has attracted the biggest of names and brightest of talents, including Glenn Close and Cate Blanchett as Blanche, Alec Baldwin and John C Reilly as Stanley, and Ruth Wilson and Vanessa Kirby as Stella. Yet when the original Broadway production opened at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre in 1947, it was a little-known actor who was catapulted into one of the plum parts. Marlon Brando’s performance as a bruising, bellowing Stanley was the making of him – and, having been immortalised on celluloid in 1951, remains the interpretation that still hangs over actors today. Arthur Miller described Brando as “a tiger on the loose, a sexual terrorist ... a brute who bore the truth”, while Gore Vidal went as far as to say that, as Stanley, he “changed the concept of sex in America. Before him, no male was considered erotic.”

Even Brando’s audition is the stuff of legend: Elia Kazan, the play’s director, gave the 23-year-old $20 to travel to Williams’s home to try out for the part. Brando pocketed the money and hitchhiked instead – arriving a week late. Yet in some ways, his timing couldn’t have been better. According to Isaac Butler’s book The Method, “Williams and his friends were sitting in the dark, occasionally getting up to pee in the woods. A fuse had blown, the toilet was broken, and the house was full of artists who had no idea how to fix either. Marlon quickly repaired both toilet and fuse, wowing the assembled guests.”

His looks and his reading of the part wowed them too – and the part of Stanley was his. Not that this casting was without its problems: Brando was an instinctive, unpredictable actor, who drove his co-stars mad. Jessica Tandy – the original, Tony-winning Blanche – fell out with him, going so far as to call him “an impossible, psychopathic bastard”.

Such unpredictability undoubtedly suited the role, however. Stanley was probably based on both Williams’s harsh, hard-drinking father and the playwright’s lover, “Pancho” Rodriguez y Gonzalez. Williams’s relationship with the latter was tempestuous; he was even accused of provoking Pancho to fits of rage in order to study his reaction for the play.

So, if Stanley was Pancho, then Blanche must be Williams – an idea given credence within Kazan’s own memoirs. “Wasn’t [Williams] attracted to the Stanleys of the world? Sailors? Rough trade? Danger itself? Wasn’t Pancho a Stanley? Yes, and wilder.”

But Williams also drew on the women in his life, to write a role that has a rare, layered complexity (Ferran will really have her work cut out for her, discovering Blanche with such little rehearsal time). Blanche is both the personification of Southern refinement, and a woman with a messy past; both vulnerable and manipulative; a snooty snob and a panicking, homeless stray.

There are traces of Williams’s own mother and sister in Blanche; both of them were highly strung, providing the model for Blanche’s hysteria and fluttering feminine fragility. (Shockingly, his sister Rose – who also inspired the character of Laura in Williams’s The Glass Menagerie– was lobotomised in 1943 after a life of mental health troubles.)

By all accounts, Tandy originated a fine first Blanche – The New York Times focused on her “superb” performance, calling it “almost incredibly true”. And audiences agreed: the show opened to a seven-minute standing ovation, and ran for 855 performances. And the play itself had instant, global appeal. Productions opened in Brazil, Cuba and Mexico as soon as 1948, while various European premieres make for a ridiculous list of mid-century talent: in Rome, it was directed by Luchino Visconti. In Gothenburg, by Ingmar Bergman. In London, by Laurence Olivier, and in Paris, by Jean Cocteau.

But arguably, what gave Streetcar lasting fame was the 1951 film. Also directed by Kazan, it retained the original cast – with the cruel exception of Tandy, replaced by a wide-eyed Leigh. As well as having fought to play Blanche in London, she had a box-office appeal following her performance as Scarlett O’Hara in Gone With the Wind. Despite Kazan’s misgivings, Warner Brothers were clear: they wanted Leigh.

But casting wasn’t the only obstacle – Hollywood censors were not likely to let Williams’s script make it to the silver screen intact. Objections were raised to some of the play’s dark content, and most problematic was the pivotal, penultimate scene where Stanley rapes Blanche, a crucial moment that Williams and Kazan fought to keep in. A compromise was agreed upon: Stanley would at least be punished for his actions. In Williams’s original script, Stanley and Stella remain together; in the film, she leaves him.

The movie was another massive success, receiving 12 Oscar nominations and four wins, including Best Actress and two Best Supporting gongs, although Brando lost out to Humphrey Bogart for Best Actor. It cemented Streetcar’s status as a cultural touchstone, with Blanche’s line “I have always relied on the kindness of strangers” and Stanley’s cry of “Stella!” still often gloriously parodied today. (Think of the Simpsons’s episode, “A Streetcar Named Marge”).

Streetcar has also inspired an opera (by André Previn, no less) and several ballets; indeed, Scottish Ballet will revive their staging of it for a tour next year. And the play is rarely away from our main stages for long – the last major UK production was in 2016, with Maxine Peake at Manchester Royal Exchange giving a compellingly contradictory performance that saw critic Matt Trueman describe her as “a mix of Margaret Thatcher and Marilyn Monroe – the Iron Lady and the ingénue”.

While usually – though not exclusively – presented as a period piece, Williams’s play continues to endure precisely because its characters are richly complicated and contradictory. “Someone once defined tragedy as being when both sides are wrong. And I would say that’s absolutely true in this case,” Rachel Weisz said when starring in Streetcar at the Donmar in 2009. “Williams’s understanding of humanity, and how messed up and monstrous and vulnerable and nasty and sweet and idiotic – just his sense of all the things a human being can be – is unbelievable.”

The play also really digs into some of the most fraught fundamentals of being human: it’s about sex, and class, and power, and violence, and the repression of desires we in fact cannot name. A story of opposites attracting and repelling; Blanche and Stanley battle it out as symbols of masculinity and femininity, of authenticity and gentility, of toughness and delicacy. Some of these might today seem like out-of-date binaries, but we aren’t exactly free of them in society yet – and Williams starkly reveals how much harm clinging to these archetypes can do.

No wonder, then, that his writing appeals to actors; Oscar winner Frances McDormand has even done the play twice, as a much-praised Stella in 1988 before a roundly dismissed Blanche a decade later. The latter was a role she was “pure and simply miscast” in, according to Variety. It’s a common complaint for a part that holds tremendous allure but very high expectations. After Close had success as the equally deluded Norma Desmond in Sunset Boulevard, Blanche probably felt like an obvious role. But The Independent’s Paul Taylor suggested in a review of the 2002 production at the National that “she comes across as a tough cookie who is engaged in an arch impersonation of Blanche ... a figure who, at moments, could be rechristened Cruella DuBois”.

And while Close’s performance winkingly acknowledged that she was a little mature for the part, other star-spangled productions have been criticised for casting actors that were too young and beautiful to convince. Ben Brantley in The New York Times described Natasha Richardson as “pretty, dewy and healthy as a newly ripened, unbruised peach” in a 2005 Broadway production. And when Weisz was Blanche, some also found her almost too alluring to make sense of Blanche’s insecurities.

For others, Weisz formed a welcome reminder that this “old maid” is only actually meant to be 30 (gulp). And, from Anderson and Peake to Blanchett in 2009, Blanche has become the preserve of, if not quite theatrical grande dames, certainly our more established female actors. While they weren’t playing against unknowns exactly – Joel Edgerton was Stanley to Blanchett’s Blanche – such high-wattage leading ladies have meant that, almost since Brando, the play has been primarily defined by who plays Blanche, rather than who plays Stanley.

The Almeida version is about to tip the balance. Ferran is a sensational stage actress and an Olivier winner to boot, but she’s not a household name. Mescal became an overnight star – and a universal crush – during lockdown, and his name will have some serious box-office power. It will be interesting to see if that dynamic affects the show – or perhaps just the make-up of the audience.

Indeed, the play only really works when both performances are brilliant. Blanche and Stanley spiral down together, horribly and inevitably. “We’ve had this date with each other from the beginning,” Stanley says grimly, before brutally forcing himself on her. His actions are unconscionable, yet the genius of Williams’s play is that it kicks around your sympathies for these troubled characters, moment by moment. Blanche can be maddening but is also hugely pitiable; Stella can be both strong and weak, and Stanley both magnetic and abhorrent. It’s what makes them all fantastic parts – and what makes the play a true tragedy.

Or as Williams put it himself, in a letter to Kazan: “There are no ‘good’ or ‘bad’ people. Some are a little better or a little worse, but all are activated more by misunderstanding than malice. A blindness to what is going on in each other’s hearts.”

‘A Streetcar Named Desire’ is at the Almeida, 17 December to 4 February; almeida.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments