Shakespeare's 400th anniversary: Celebrating heroism, debauchery and unsparing human truths

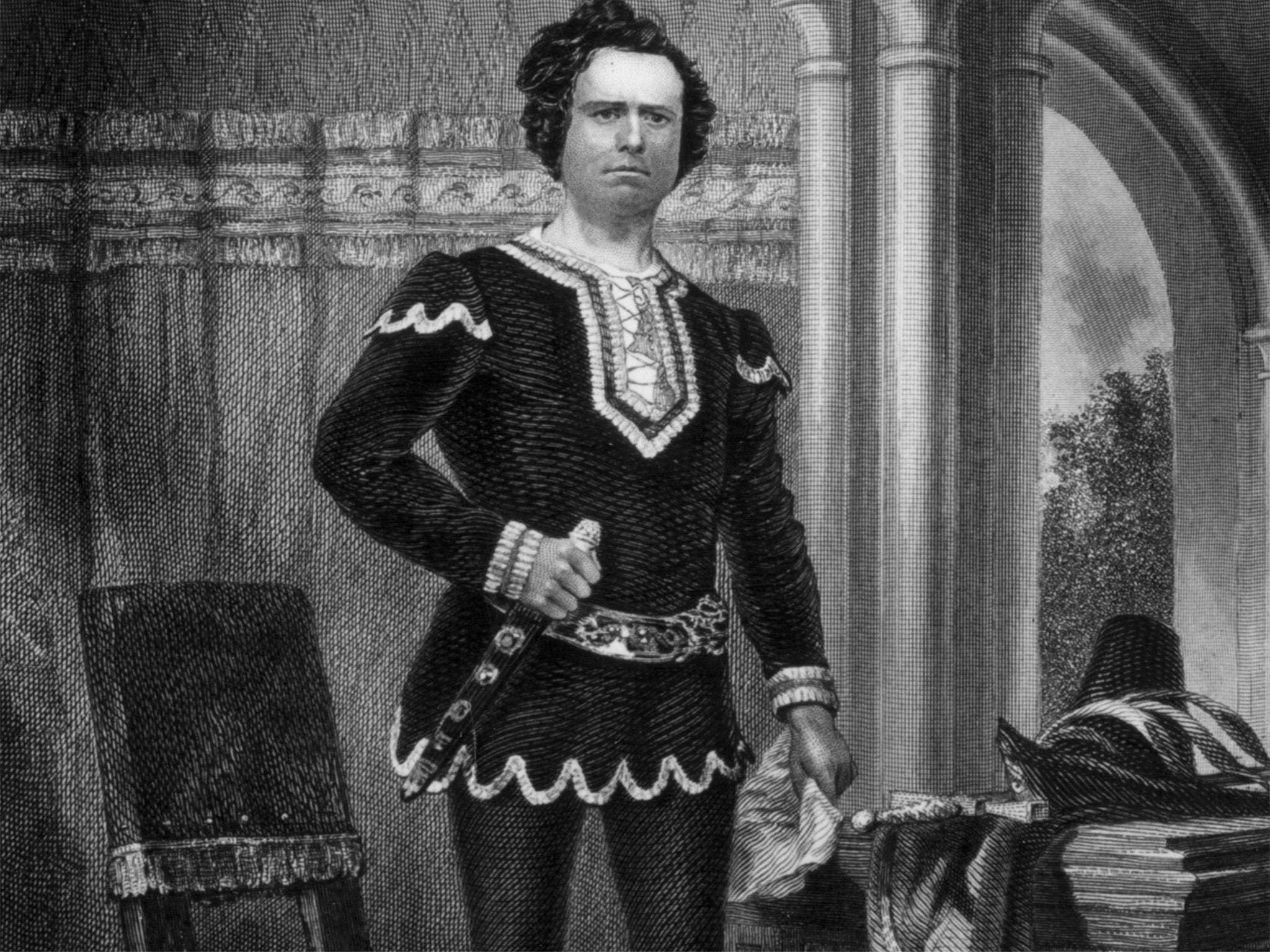

In the fourth part of our series marking the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, Antony Sher celebrates a pair of extraordinarily rich history plays

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.People often ask me which is my favourite Shakespeare play. I always answer the same way: it’s whichever one I’m doing at the moment.

So it’s Henry IV, Parts One and Two for me, with RSC productions, currently on an international tour.

What I love about the twin plays is their giant, panoramic view of England, from the passionate political arguments in the court of King Henry IV to the riotous nights and hungover mornings in the Boar’s Head Tavern in Eastcheap, and everything else in between: whether the chaotic violence of the Battle of Shrewsbury or the peace and silliness of Justice Shallow’s country estate in Gloucestershire.

And what a gallery of characters people this England! The king himself, who, as Bolingbroke, has usurped Richard II’s throne, and is now sick, fuming with anger and guilt. Prince Hal, who journeys from a recklessly wild youth to the sober, weighty responsibility of kingship. The battle-hungry Hotspur, leader of the rebels. The red-nosed Bardolph, the explosive Pistol, the Beckettian double-act of Shallow and Silence. And the women: Lady Percy, a fiery match for her husband, Hotspur; the tavern’s hostess, Mistress Quickly, who argues and adores with the same scatter-brained energy; the young prostitute Doll Tearsheet, who has a surprisingly tender affair with the fat old knight, Sir John Falstaff…

Falstaff is the part I’m playing, so he holds my attention in a special way. The renowned American Shakespeare scholar Harold Bloom has said that Falstaff and Hamlet are the Bard’s greatest creations. Falstaff is an astonishing Lord of Misrule. He shocks us even now, so what must he have been like to Shakespeare’s audience? A man who, while people are fighting and dying on the battlefield, says that honour is worthless (“I’ll none of it”); that he’s exhausted (“I am as hot as molten lead”); and that it’s best to play dead (“Time to counterfeit”).

Falstaff is a lying, cheating thief and highwayman. He’s an obese and alcoholic bullshitter. He’s a completely untrustworthy friend: the minute a character leaves the stage, Falstaff turns out front, and rubbishes them (he does this with Hal, Poins, Shallow, and others).

And yet we love him. We, the audience, love him. Why? Because it’s one of Shakespeare’s gifts, or, you might say, one of his tricks. In his ceaseless quest to make us see ourselves, he shows our reflections good and bad. And so, amazingly, we end up enjoying the moments when, say, Richard III or Iago confide in us, outlining their terrible plans. In real life, we’d run a mile from these characters. But in the strange safety of the theatre, with an invisible yet invincible curtain between us and them, we can license their immorality, and even rejoice in it. It’s us recognising our other selves, it’s our secret appetite to be both Jekyll and Hyde.

Falstaff isn’t nearly as lethal as Richard III or Iago, but he’s something of a monster too, and, as someone who’s played all three parts, I can testify that they’re a treat to put in front of an audience. But Falstaff’s outrageousness isn’t enough for Shakespeare. He gives the fat knight a cruel and lonely end. Part One begins with Falstaff and Hal as the best of buddies, Part Two finishes with Hal (now Henry V) rejecting Falstaff: “I know thee not, old man.”

The rejection scene is, I think, a perfect example of Shakespeare’s genius, because it demonstrates his unsparing truth about human behaviour. Hal must reject Falstaff. Hal is king now. And as England’s new ruler, there’s no more place for the Lord of Misrule.

‘Henry IV Parts I and II’ are part of the RSC’s King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings which played at the Barbican earlier this year and are currently touring to China, Hong Kong and New York

Shakespeare at a glance: Henry IV Parts 1 and 2

Plot

Three men named Henry – the king, the prince and Hotspur – all disagree in one way or another. The prince’s drunken debauchery aggravates the king, who refuses to pay ransom for the imprisoned brother of Hotspur, who plots to depose the troubled monarch. The bloody battle of Shrewsbury brings the death of the rebellious Hotspur, whose armies are quashed by the loyalist forces. Prince Henry drives off the rest of the rabble, takes the throne when his father dies – and disowns his dissolute ways and friends.

Themes

Loyalty (personal vs public); rebellion; fathers and sons; responsibility; perseverance.

Background

Both parts were written in the late 1590s, with a break in the middle of the second for Shakespeare to knock out The Merry Wives of Windsor. Sir John Falstaff was originally called Oldcastle – the same name as the Lollard martyr John Oldcastle. Political pressure is thought to have persuaded the playwright to change the name. A BBC production of the two plays earned Simon Russell Beale a Bafta for his portrayal of Falstaff.

Key characters

Henry, Prince of Wales: the wastrel Prince Hal who drives off the fearsome Hotspur in Part 1, then shrugs off the dissolute Falstaff in Part 2.

Henry “Hotspur” Percy: young, ferociously heroic star of the rebellion in Part 1.

Sir John Falstaff: the corrupt, manipulative yet charismatic friend of the young prince.

Famous lines

“By heaven, methinks, it were an easy leap, To pluck bright honour from the pale-fac’d moon” – Hotspur sums up his martial spirit, Part 1, Act I, Scene 3.

“The better part of valour is discretion” – Falstaff’s fighting code, Part 1, Act 5, Scene 4

“There live not three good men unhanged in England; and one of them is fat and grows old” – Falstaff’s lament, Part 1, Act 2, Scene 4

“Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown” – King Henry IV reflects on royalty and insomnia, Part 2, Act 3, Scene 1

“I know thee not, old man; fall to thy prayers” – the new Henry V (formerly Prince Hal) rejects Falstaff, Part 2, Act 5, Scene 5

Echoes

Gus Van Sant’s My Own Private Idaho (1991) is loosely based on Henry IV, Parts 1 and 2.

King Henry’s “Uneasy lies the head …” quote appears in the opening frame of Stephen Frears’ The Queen (2006).

Luke Barber

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments