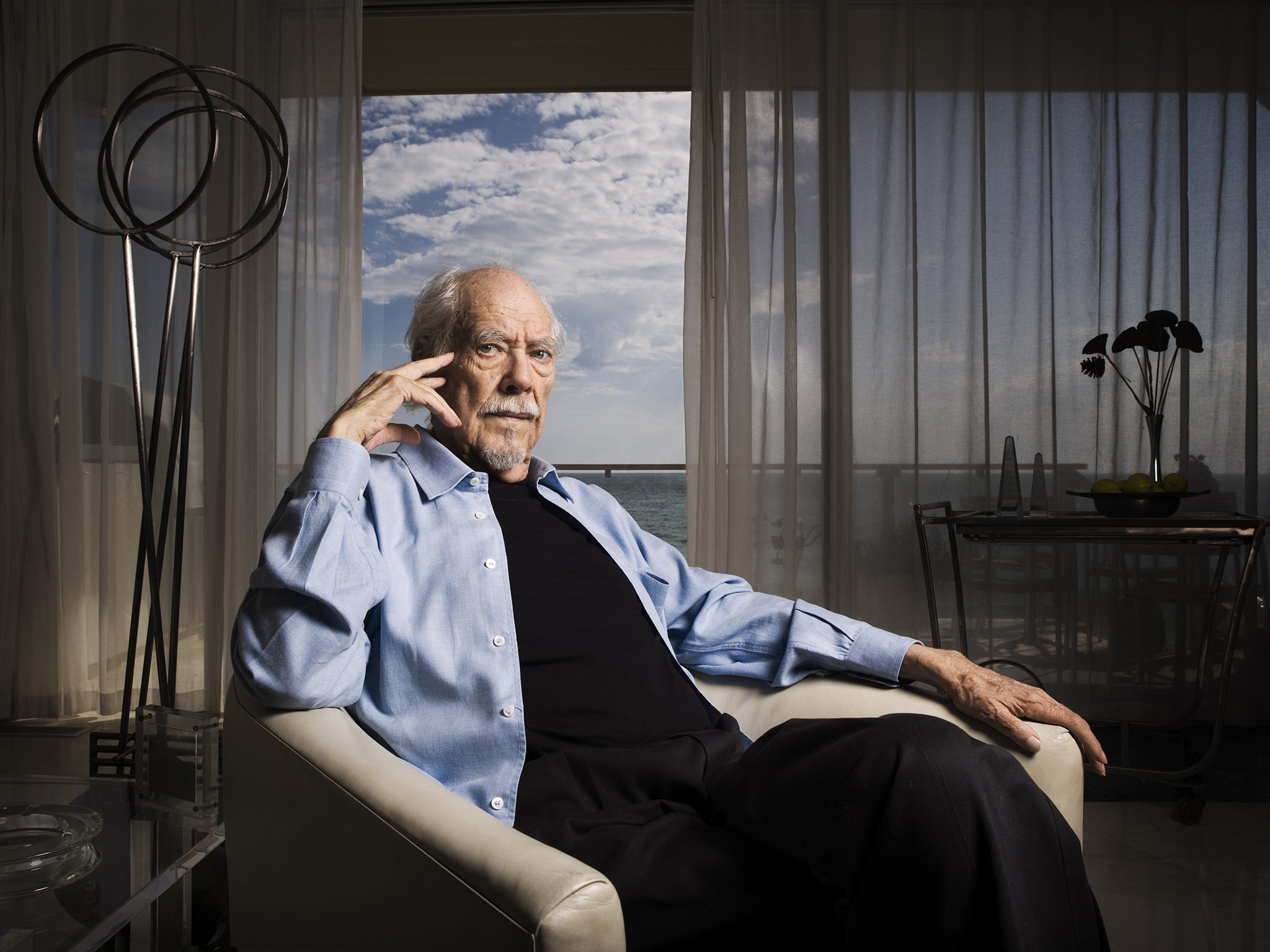

Robert Altman's wife Kathryn Reed on why she can't forgive 'impossible' Kevin Spacey

As a documentary about the legendary filmmaker is released, his widow opens up about his disastrous last play at the Old Vic

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There is an awkward moment when Kathryn Reed Altman enters a room in the Mayfair Hotel. I’d just been telling Ron Mann, who has made Altman, a documentary on her husband of 47 years, that I’d wasted my money seeing Robert Altman’s appalling adaptation of the Arthur Miller play Resurrection Blues at the Old Vic just a few months before his death in 2006.

There is no mention of the play in the film and Mann tells me the person to ask about the experience is his widow. Indeed, while Mann has his name on the directing credit, it becomes abundantly clear that it’s Reed calling the shots.

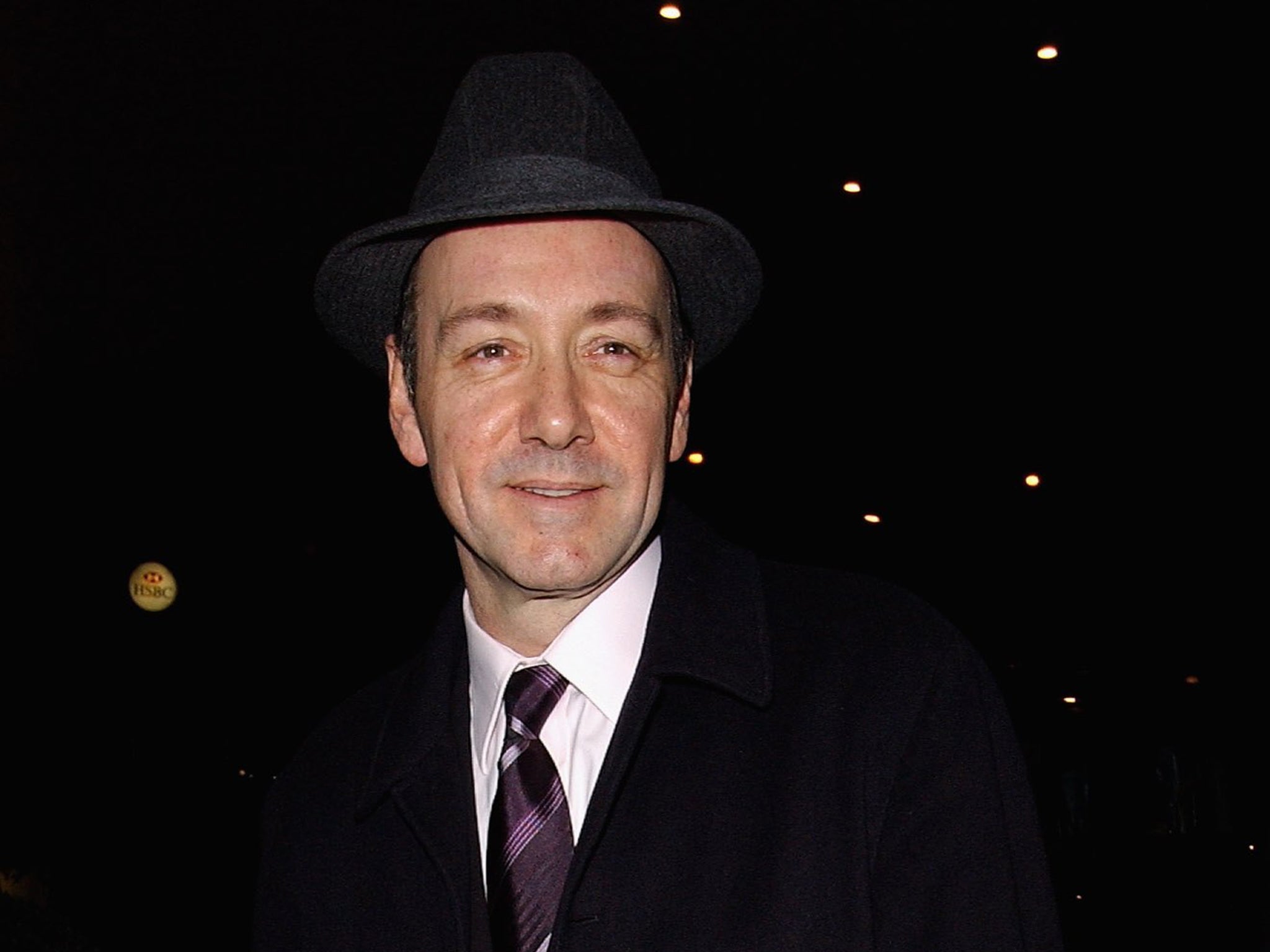

Abandoning her walking cane, Reed may look frail, but she has the will of a bull. When I mention the play to her, Reed doesn’t try to defend it. The actress Jane Adams reportedly stormed out of the play, although it was said that she left the production by mutual consent, and it closed early after a critical mauling and performing to half-empty auditoria. She says that the play’s weakness had nothing to do with the directing, nor the cast, and lays the blame on Kevin Spacey, the artistic director of the Old Vic.

“The behaviour of Kevin Spacey was really unacceptable,” says Reed. When I counter that the popular rumour is that the cast didn’t know their lines and were unprepared, Reed asserts: “That is untrue. That is not the case at all. There was nothing wrong with that. It was just a tough play and it was hard to get it together enough for the audience and it was a gamble.”

So why the ire with Spacey? “Kevin Spacey is impossible and he was the director of the Old Vic at the time. Bob handled it very well, there were no open arguments or fist fights, there should have been, and that’s my answer.” And with that she draws a line in the sand.

Mann needed Reed’s approval to make Altman, which is crammed full of home movies, family photos, behind-the-scenes footage, clips from his feature films and unreleased short films. One, called Pot au Feu, is a celebration about smoking marijuana and another, The Party, highlights his love of throwing big soirees. The story is told using interviews given by Altman, and when there are gaps, Kathryn Reed steps in, and, less often, we hear the tones of his sons Robert and Stephen, who both worked on the crew of numerous Altman productions.

Covering such a huge body of work in 90 minutes ensures that the movie is more an introduction to Altman than any profound analysis. His life as a theatre director is dealt with cursorily as it concentrates on his independent film career. The interviewees, ranging from Bruce Willis to Paul Thomas Anderson, are only asked to describe what they think “Altmanesque” means.

The filmmakers have already given their own interpretation by starting the film with a dictionary-type entry of “Altmanesque”, which gives the following meanings: “characterised by naturalism, social criticism, subversion of genre; not conforming to predictable norms; indestructible”.

The documentary takes us from Altman’s birth, in Kansas City in 1925, to fighting as a pilot in the Second World War, to his nascent career as a Kansas City industrial-film maker at breakneck speed.

His first two marriages are dealt with by showing two photographs of his ex-wives, LaVonne Elmer and Lotus Corelli, with Reed in voiceover stating, “he had already been married twice but those marriages didn’t last very long”. They were for five years and three years respectively.

There is greater insight into the partying ways of Altman when she says that, when they met on the set of TV show Whirlybirds, Altman didn’t say hello – “He asked: ‘How are your morals?’ I said: ‘A little shaky.’” As Reed puts it, after their first date, she never had to work again.

Altman forged his career in television, where his desire for realism often got him into trouble. When working on the TV show Combat! in 1963 he wanted to use his own wartime experience to show a shell-shocked soldier struggling with the trauma of war, but when the dailies came in, he was fired from the production – though after he was sacked the editor would sneakily ask him how he wanted it cut. The show won an Emmy. He quit working on television altogether when he wasn’t allowed to cast a black actor in an episode of Kraft Suspense Theatre.

The documentary is not scared about talking about the rollercoaster nature of Altman’s career, the highs of MASH and Gosford Park, the lows of Images and Popeye.

Reed says that Altman was rather sanguine about the critical reaction to some of his films. “Yeah, he was disappointed when the audience didn’t get it, he just didn’t dwell on it. He just went to the next one. He didn’t get into deep depression or climb the walls. I don’t know if ‘rational’ is the word I would use, he stood by his own choices, the bad reviews took their toll but he didn’t dwell on them.

“What I like about what Ron did is that he got the balance of the highs and lows right, and doesn’t dwell on the renegade and maverick side of him, which I’m not saying wasn’t there, it was nice the way Ron got into the real man.”

Indeed the film is best when it delves into Atman’s life away from set, his partying, the heart transplant he kept secret for a number of years. Reed pinpoints two innovations that have ensured that the director is lauded as one of the greatest of all time: first the recording of sound on radio mikes so that he could overlap and play with the dialogue in the edit and, second, the freewheeling camera work.

In The Long Goodbye the camera never sits still, and the opening for The Player is the clear template for this year’s Oscar best picture winner Birdman. His innovations changed cinema and perhaps the greatest tribute that could be paid is that they have now become movie standards.

Mann made his own discoveries spending time with Reed and the six children she raised with Altman, three from his previous marriages, one from her previous marriage, one they had together and one adopted: “If you want to know where overlapping sounds come from, just go to the Altmans’ for dinner.”

Altman’s son Stephen says Altman put films before his family. “Steve has taken a lot of heat for that line, he can’t take it back, it was a little out of proportion,” says Reed. “We have a very unconventional life, there is 20 years from the oldest to the youngest and it didn’t work that way, every location and every film was different.”

‘Altman’ is released on 3 April

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments