Rape on stage: Hard to stomach, but the brutality of its depiction might help us as a society to wake up to rape culture

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

“He lifted me off the floor, pulled up my knickers. He spent some time rearranging me I remember. He smoothed my hair back off my face. Be our little secret, baby Leah yeah?”

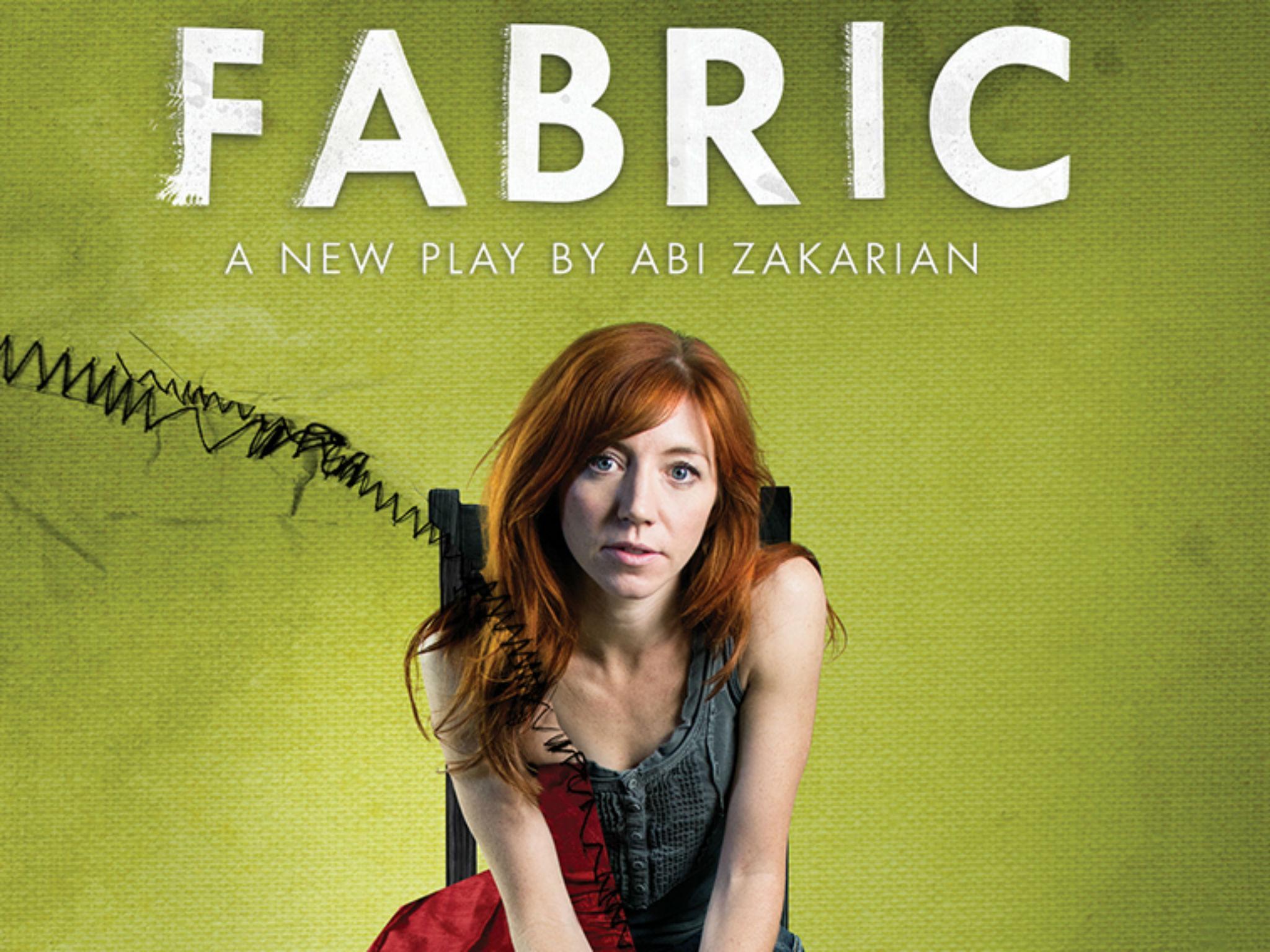

So concludes an eye-wateringly brutal rape scene in a new play by Abi Zakarian. The one-woman show, Fabric, is a searing look at the contradicting expectations of women in modern society, the roles we play and the ones pushed upon us, making the point that non-consensual sex is the best way to break, subjugate and undermine our gender.

We’re used to rape in theatre. You can’t go and see West Side Story or most Greek tragedies without a hint, suggestion or full-on depiction of sexual violence. But recently there has been a trend for overt rapes onstage that have left audiences reeling.

Edward Bond’s Dea, a loose retelling of Medea, which recently premiered at the Secombe Theatre in Sutton, features two horrifying acts of sexual violence, one of which involves necrophilia and the other a mother molesting her son. OK, so the clue that it wasn’t going to be cosy might have been in its classical roots, but Bond has a surprising explanation for these scenes, claiming in the play’s programme: “I write of the rape of a corpse with a beer bottle to bring back dignity to our theatre.”

Earlier this year newspapers went into overdrive at reports of audience members keeling over at a National Theatre production of Sarah Kane’s Cleansed. The play, which opens with heroin being injected into a man’s eye, and is premised on the idea of two couples being tortured to prove their love, is no picnic. And, like the playwright’s famously controversial Blasted, it features precisely described acts of sexual violence and places them centre stage. Kane’s work has always provoked walk-outs, but at least five people were reported to have fainted in response to Cleansed despite the cinema-style warning that it contained “graphic scenes of physical and sexual violence” before curtain-up.

Audiences were similarly overcome at a 2014 Shakespeare’s Globe production of Titus Andronicus (one of those who fainted was The Independent’s theatre critic). The goriest of Shakespeare’s folio features the rape of Lavinia whose tongue is cut out and her hands severed so she can't speak or write of the crime made against her. It is notoriously difficult to stage, and those at the front of Globe’s “groundlings” area (people standing at the very front) needed umbrellas to keep the fake blood off their clothes.

And last year the Royal Opera House sparked a sea of headlines and walk-outs with Italian director Damiano Michieletto's new take on Rossini’s Guillaume Tell which replaced a Swiss folk dance scene with a choreographed gang rape. On its opening night audiences reportedly booed and heckled and the ROH was forced to issue warnings. But, and interestingly, Kasper Holten, the opera director at the ROH, sent a joint statement to ticket-holders at the time stating: “It has never been our intention to offend members of the audience, but for the scene to prompt reflection on the consequences of such terrible crimes on their victims.”

George RR Martin said something similar when the rape of Sansa Stark in season five of Game of Thrones sparked global outcry. Speaking to Entertainment Weekly, the 67-year-old author said: “Rape, unfortunately, is still a part of war today. It’s not a strong testament to the human race, but I don’t think we should pretend it doesn’t exist.”

That’s the point, really, because while we might live in a “rape culture”, where victims are named and shamed on social media and described with words such as “whore”, their clothes and behaviour used as mitigating evidence in court, we still find it hard to look directly at the issue of rape. We see it all the time through televisions, on film and in pornography. It is joked about and spoken about in knowing whispers. But when it is put onstage in front of us it makes us feel ill.

There’s a good reason for that. Because it is reprehensible and revolting. But rape happens every day and theatre has a duty not to ignore it. Sure, it is sensationalised on stage. Everybody knows sex sells. And similarly you could say rape provokes controversy, media coverage and ultimately curiosity amounting to ticket sales. That was one of the main criticisms levied at Guillaume Tell – although it is far from the first opera to have gone down this road.

But what Fabric, which is on tour from 22 June, can lay claim to is giving voice to the victim and their experience – something none of the other productions mentioned here do. It is a one-woman show so doesn’t allow for brutal realism but instead the central character Leah (Nancy Sullivan) describes what happened to her, how she felt physically, the smell, the sink repeatedly digging into her stomach, as she is raped in the toilet by a friend of her husband’s on a night out.

Playwright Zakarian says: “I wanted it very much to be her [Leah] telling it. Using her words. You have this thing in the reporting of rape cases where, quite rightly, the survivor remains anonymous. They are rape victim one, or Jane Doe, and it dehumanises them. So this was an opportunity to say this could be your sister, your mother, your friend.”

The play deals more generally with Leah’s life up until the rape, when: “She takes herself back to where it happened to her. She goes back into that moment and slowly starts reliving it in her head,” Sullivan explains. “And it becomes this vomit, really, of words. The feel of it, the sensations, a subconscious stream that seems a very present recollection of the trauma.”

This approach might not sound groundbreaking, but it is. Rapes often happen offstage or are referred to in conversation in drama. But an unflinching description of every element of a sexual attack is hard to listen to and it will be interesting to see how audiences react when it arrives in theatres. There is no fake blood, no knickers around her ankles and the attacker is as faceless as the victim normally is in media coverage. But in a world where mobile phone footage of actual rape surfaces regularly on the dark web we need to as a society look at it squarely in the face to see what we're dealing with. And Fabric is a good start.

Tour dates: 22 – 25 June, EM Forster Theatre, Tonbridge; 2 July, Theatre Royal, Margate; 5 July Old Fire Station, Oxford; 6 – 7 July, Mercury Theatre, Colchester; 8 – 9 July, The Cryer, Carshalton; 11 – 14 July, New Wimbledon Studio, London; 20 July, The Hawth, Crawley; and 21 – 22 July, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury. Udderbelly at Edinburgh Fringe in August

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments