Rambert: Britain's oldest dance company still thriving on reinvention as it approaches its 90th birthday

Rambert has transformed itself from a ballet troupe into the UK’s flagship contemporary company

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Britain’s oldest dance company is no stranger to change. Rambert, which turns 90 this year, has discovered many of Britain’s leading choreographers, taken a long journey from the notoriously tiny Mercury Theatre to shiny new premises on London’s South Bank, and transformed itself from a ballet troupe into the UK’s flagship contemporary company. It’s a story that moves from the 1920s avant-garde to wartime dancing for munitions workers, 1960s radicalism and more.

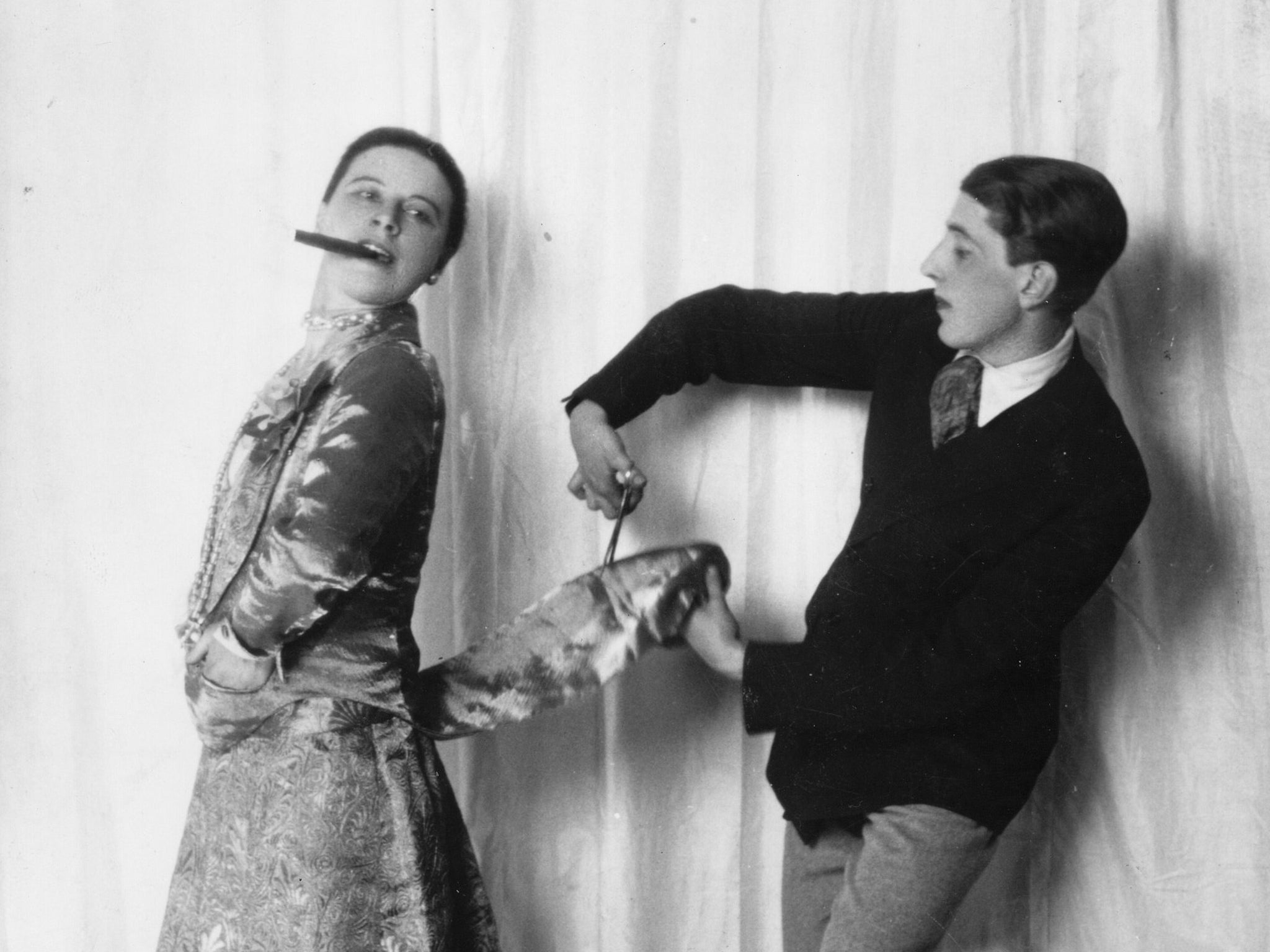

The company was founded by the Polish dancer and teacher Marie Rambert, a woman of huge energy and an eye for talent. By the time she came to London at the outbreak of the First World War, she had already weathered plenty of artistic storms. She came to ballet when Sergei Diaghilev, impresario of Ballets Russes, hired her to help with the creation of The Rite of Spring, believing that his star dancer and choreographer, Vaslav Nijinsky, needed help with the complex rhythms of Stravinsky’s score. In 1913, Rambert danced in the ballet’s premiere, when the Paris audience rioted in response to the shattering music and angular choreography.

After leaving the Ballets Russes, and settling in London, Rambert established herself as a ballet teacher with theatrical flair and a host of artistic contacts. At a time when British dancers would hide behind Russianised stage names, Rambert’s students didn’t pretend to be exotic: they danced as themselves, and danced with confidence. She drew out their personalities as well as working on their techniques – and often discovered extra talents. Her students would include the choreographers Frederick Ashton, Antony Tudor and Agnes de Mille, who all went on to international careers. Throughout the company’s history, its dancers would be an important source of new works: the current season features works by past dancers Mark Baldwin, Christopher Bruce, Didy Veldman and Alexander Whitley.

The company dates its beginning from 1926, when Ashton created his first ballet, A Tragedy of Fashion, performed by Rambert’s dancers. Ashton, ambitious but impractical, liked the idea of costumes by Chanel. “Nonsense,” said Rambert. “We haven’t the money”. Instead, she introduced him to the painter Sophie Fedorovitch, who would become one of Ashton’s closest friends and collaborators. A Tragedy of Fashion was chic and witty, becoming its own fashionable success; it hasn’t survived, but it launched a number of careers, and a company that had a sense of style and theatre despite its shoestring budget.

Ballet Rambert, as it became in 1935, found its first home at the Mercury Theatre, a tiny space in London’s Notting Hill. The stage was no more than 18ft square: hardly space to swing a cat, let alone a ballerina. You can see a glimpse of it in the 1948 Powell and Pressburger movie The Red Shoes: there’s only just room for the corps de ballet to get on and off stage. (Rambert herself appears in the film, wincing at a mistake in turning the record over – no room for an orchestra, either.) The intimacy may have helped some of the works created at the Mercury, such as Jardin aux Lilas, Tudor’s 1936 drama of repressed love; he sprayed the auditorium with lilac perfume on opening night. Jardin aux lilas went on to be a hit in much bigger theatres and last year, American Ballet Theatre danced it in the 3,800-seat Metropolitan Opera House in New York.

Though Rambert had a gift for spotting and encouraging talent, she was less good at forward planning. The choreographers she discovered would move on to bigger companies and wider opportunities: Ashton went to Sadler’s Wells, the company that would become The Royal Ballet, while Tudor left for America.

When the Second World War broke out, the intimate repertory proved useful. Touring to entertain munitions factory workers, they could perform in canteens and improvised performance spaces, to audiences snatching some art along with their sandwiches. Ballet while you eat was popular with civilian audiences, too: back in London, Rambert’s was one of two companies offering short daytime performances, with lunchtime ballet swiftly followed by “tea ballet” and even the irresistibly named “sherry ballet” for early evenings. Wartime audiences were hungry for dance – something that The Royal Ballet’s empire-building founder, Ninette de Valois, used to boost her company to national status. Rambert was less canny. Similarly, she did less well out of the post-war ballet boom. While the Sadler’s Wells company achieved international celebrity and stronger financial footing with tours of North America, Ballet Rambert’s visit to Australia and New Zealand was hugely popular but financially disastrous.

The company was turned around by a drastic change of direction. Norman Morrice, another choreographer discovered by Rambert, was fascinated by the versatility of American dancers and wanted to introduce new kinds of training. But the real change came from the dancers, explains Rambert archivist Arike Oke. “There was a schism among the dancers themselves,” she says. “It didn’t all come from above: the dancers went to Marie Rambert as a group, saying, ‘We don’t want to do classical repertoire any more, we want to be moving forward.’ They thought they were being left behind by some of their American counterparts, all of the experiments happening over there. One of the dancers, Joe Scoglio, told me that the dancers were prepared to leave, to form their own company. Rambert said, ‘Oh, no, darlings, you are the company!’”

The new-style Rambert, launched in 1966, was experimental but still tentative, with dances created by company members. In 1967, Morrice brought in American choreographer Glen Tetley. Staging his Pierrot Lunaire for Rambert, he looked right through the company for a dancer to play the moonstruck clown. In the back row, he spotted Christopher Bruce – Rambert’s next star dancer. Bruce would also prove to be its next star choreographer, making dances with an eye for character and drama, and later still one of its artistic directors.

When the company made its switch to contemporary dance, it was eager to tap into the 1960s zeitgeist, taking risks with style and content. Several dancers made apocalyptic works, inspired by fear of nuclear war. For Tetley’s 1967 work Ziggurat, the performers were asked to crochet their own costumes. “The costumes haven’t survived,” Oke explains, “but when you look at photographs, there wasn’t much to them. They look like fisherman’s netting, and you can see Y-fronts underneath it. It’s amazing how much that was embraced by the public – what we would see as quite dark, intellectual works might not be accessible these days, but the public really loved it.”

Over time, the pendulum swung back, as the company’s audiences and choreographers wanted to explore stories again, or to experiment with pure dance imagery. Several of the company’s artistic directors, including Richard Alston and current director Mark Baldwin, have had fine art as well as dance backgrounds; they’ve brought in painters, including Howard Hodgkin and Gerhard Richter, to work with the company.

Though Rambert became a contemporary company in 1966 and became Rambert Dance Company in 1987, its dancers still come from classical as well as contemporary backgrounds. Current director Mark Baldwin, says he’s looking for diversity. “When people come and do class, one of the first questions I ask is, ‘Do we already have someone like that? Am I just doubling up?’ It’s the variety – in terms of experience, of technique, what they offer to the whole group. And they feed each other, choreographically.”

After decades of cramped conditions, from the Mercury to two former homes in Chiswick, Rambert now has a RIBA award-winning building, home to studios, a fine archive and a base for the company’s outreach programmes in schools and in the community. And it has changed its name again, simplifying it to just “Rambert”. “It’s because the work we do is so much more than the tour, so much more than the performances,” Oke says. “The name has to encompass everything we do.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments