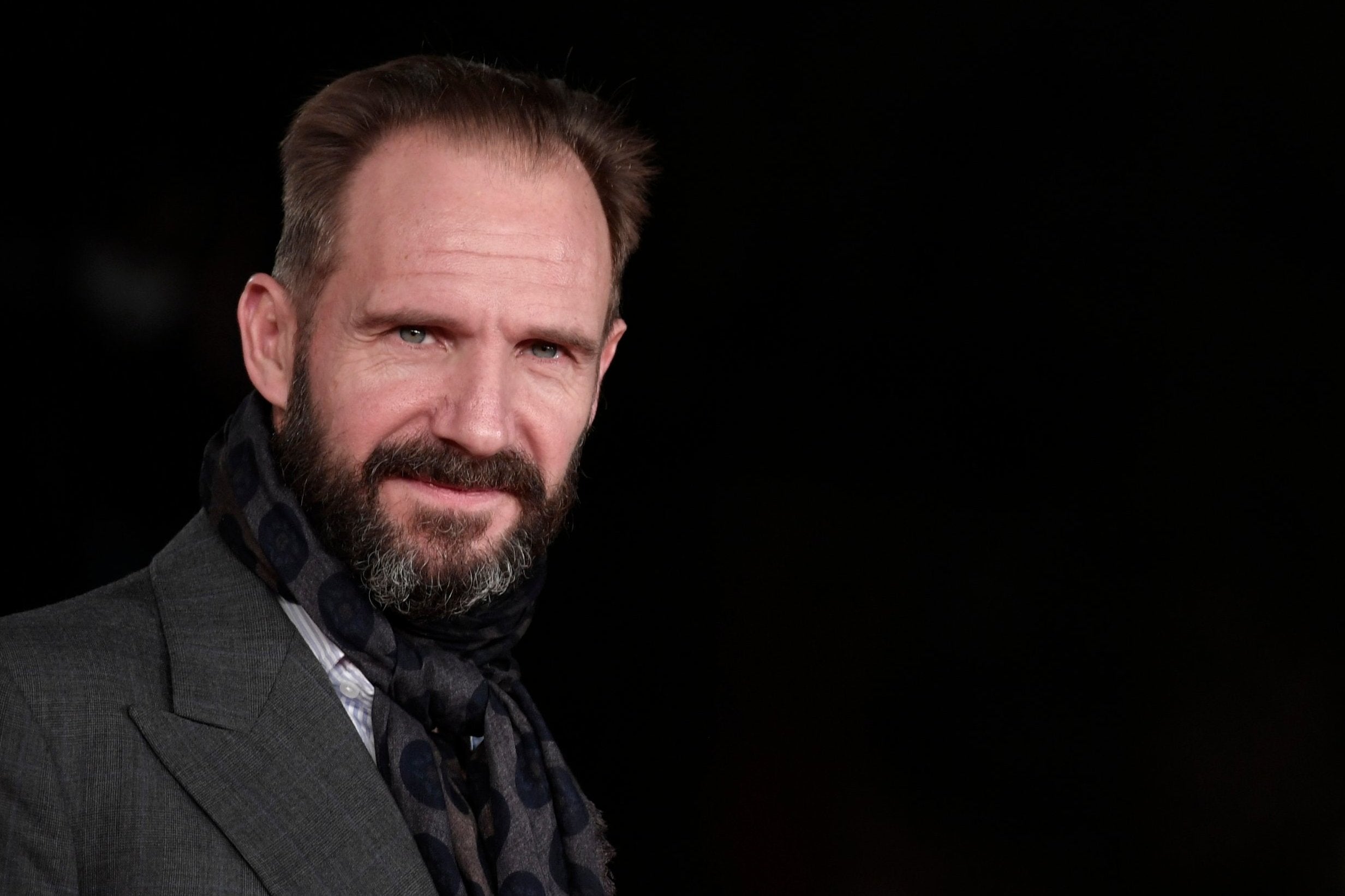

Ralph Fiennes interview: 'The film world is too horrendous'

The actor on his latest role in the National Theatre's 'Antony and Cleopatra' and its themes of ageing, power and masculinity, his love of Shakespeare, and not always being typecast as a 'twisted English intellectual anxious type'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Ralph Fiennes is playing a man on the downward spiral of his life. From tomorrow, he will bestride the stage of London’s National Theatre as Antony in Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra.

“I think it is brilliant about a certain age,” he says, with a quick laugh, “where he is aware of the youth coming up behind him and of being on a descending slope; where you can see the body is changing and things are different. I feel he articulates that. His sense of being challenged by youth and his anxiety about his own potency.”

At 55, Fiennes clearly has some sympathy with Antony’s concerns, but in many ways his career is thriving as never before, exhibiting a healthy and impressive variety that ranges from playing a demented East End villain in Martin McDonagh’s In Bruges, to a prissy concierge in Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel, to a dance teacher Alexander Pushkin in The White Crow (in Russian), a film about the dancer Rudolf Nureyev, which he also directed. Not to mention the incarnation of evil, Lord Voldemort in the Harry Potter movies.

“It’s been a wonderful pleasure, delight and a thrill that I haven’t always been cast as a twisted English intellectual anxious type,” he says. “I have been happily surprised by the parts people have asked me to play. And I have chosen by gut feeling. Whenever I have chosen with my head, thinking it might be a good career move, then it’s always been an analytical choice and it’s never felt right.

“But when it’s a gut feeling – that’s a good part, that director is great, that script feels good – it doesn’t matter if they have been successes or not but I haven’t regretted them because the choice to do them has been a feeling in here” – he indicates his stomach – “rather than there” – and he gently touches his head.

He signed up to play Antony, directed by Simon Godwin, after enjoying considerable success in partnership with the same director in George Bernard Shaw’s Man and Superman in 2015. It was another quick decision. They sat down to discuss what they might do together next, and Antony soon came up.

“I think it’s a part that’s huge but has been a bit overlooked,” Godwin says. “He’d seen the Judi Dench and Anthony Hopkins version and been very affected by it.” They both went to see Sophie Okonedo in her devastating performance in Edward Albee’s The Goat, or Who Is Sylvia? and immediately invited her to play Cleopatra.

We meet just before opening night, in the slim space between a rehearsal and a preview. Fiennes, in a crisp blue shirt, open at the neck and the waist, looks relaxed and tanned as he settles on a battered grey sofa to talk. Godwin settles in next to him, and the complicity between them is obvious.

“Simon is very tolerant,” says Fiennes. “I make observations that most actors wouldn’t. I step into his territory, but I can’t help seeing things.” Godwin smiles benignly. “That’s why I like working with Ralph because a partnership between actor and director is about much more than blocking where everyone is standing. It is about some kind of conception of a world and of a character.”

Fiennes grins back, with a look of slight mischief. “Simon is unusual in his continual openness to what actors bring. Actors are like children. We want to be allowed to play but we want the parental boundaries as well to give us confidence. It’s a funny dynamic.”

He is so deeply immersed in Shakespeare, so recently out of rehearsal, that he quotes huge chunks. The words seem to envelop him. His portrayal of Antony is not his first Shakespeare’s hero: he has given us Hamlet, Richard II, Richard III and others, all played onstage with conspicuous success. In his directorial debut on film, he played another Roman leader, Coriolanus, making the tragedy visceral and contemporary.

“The Roman plays and the histories are full of questions about power, what it means to hold power and the nature of the individual holding power. This play is brilliant about the man who has had power and is losing it.” Godwin chips in: “And about masculinity as well.”

It is the balance between the worlds of Antony and Cleopatra, and Antony’s constant tug between the demands of duty and power and the relaxation of love and luxury that creates the tension in the play – and precipitates the tragedy.

“He is very released at the beginning into the erotic territory of Cleopatra and union with her. But he knows in terms of his political life it’s not good,” Fiennes muses. “He’s this really divided man.”

Godwin adds: “The play is asking what are the conditions in which men can age happily? In the present political structure, we are thinking of these men who are of a certain age reacting in a certain way. Antony endlessly has two choices.”

Fiennes is enjoying playing opposite Okonedo, sharing the load of the play with such a strong woman. “The part of Antony is not as big as Hamlet, Richard III or Coriolanus in terms of words or time on stage, but it has a tragic arc as big as theirs, and it feels like a very big part.

But that tragic arc is in tandem with Cleopatra’s: you carry it together. The energy is shared and you can only inhabit the journey of Antony if you are in synch with Cleopatra: the two spirits define each other all the time. That’s the big difference.”

But what he is enjoying most is simply being back with Shakespeare, whose words have run like a thread through his diverse and rich career. “As I get older, Shakespeare really speaks, perhaps because you have more perspective on life and its complications and choices,” he says, thoughtfully. “I was introduced to him when I was very young, and I’ve always felt at home with the language. It’s a challenge, but I’ve always loved it – reading Shakespeare, playing it, seeing it. I just think his overview of humanity is unsurpassed and the language – it’s extraordinary.

“There is a profound spirit in Shakespeare that we can’t really put into words, but audiences keep coming and actors keep wanting to play it. We get excited when we hear that there is such and such a production because there must be some magical insight into who we are that is continually arousing to us.”

The play feels like a particular joy because he is at the National off the back of finishing directing – and acting in – The White Crow, written by David Hare, which is due to be released next year, after a run at the London Film Festival.

He is proud of the film, which was his idea, but appeared on screen against his will. “It was something I didn’t want to do but I was made to feel my participation as an actor would help to finance the film. The whole thing was just stress. The film world is too horrendous. Finance, money, everything about it hinging on what the distributors feel they want. I’ve been very lucky. I’ve been allowed to make three films creatively unimpeded, but it has been very difficult and the stress and anxiety level is tough.”

He’d like to direct on stage one day. But in the meantime he is relishing the freedom of acting. In the end his approach is to aim for simplicity. “The thing about playing Shakespeare is if you say the lines, you are the character. I was talking to Ian McKellen the other night and he said Shakespeare wouldn’t have had a concept of playing characters. If you say Hamlet’s lines as yourself, you are Hamlet.

“Essentially it is quite simple. You just have to be in the moment of what you are saying because the language carries so much. You are saying those thoughts as I am speaking to you now, in the present moment, trying to be as clear as I am.” He smiles, briefly again. Then suddenly he is off, ready to add another Shakespeare hero to the Fiennes pantheon.

Antony and Cleopatra plays at the National Theatre from tomorrow until 19 January: nationaltheatre.org.uk. Broadcast live as part of NT Live to cinemas worldwide on 6 December

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments