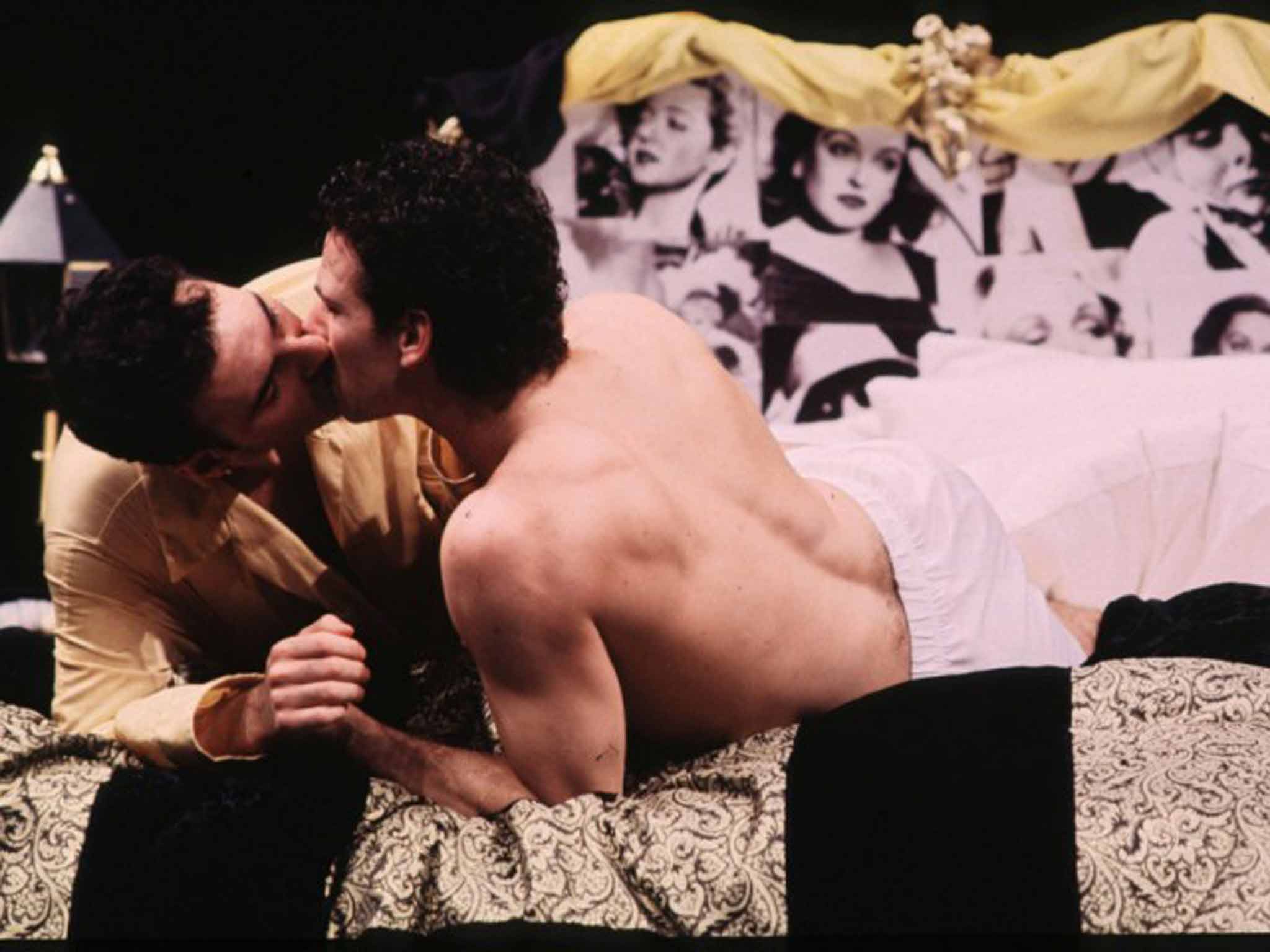

'My Night with Reg': No 'pink play' stereotypes

The Donmar's revival of Kevin Elyot's 1994 tale of gay friends, 'My Night with Reg', is given added poignancy by being staged only a month after its creator's death. The director, Robert Hastie, talks to John Nathan about its humanity

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Kevin Elyot's My Night with Reg opens at the Donmar Warehouse next week it will be a revival that is more than tinged with sadness. Just six weeks ago the playwright died. The show's director Robert Hastie had been in regular contact with Elyot who was giving his full attention to every aspect of the production, from possible (minor) changes to the text, to what Guy (Jonathan Broadbent) should have on the walls of his flat where the play is set.

Although Elyot had been suffering from a long illness, his death at the age of 62 was still a shock. He first became ill not long before My Night with Reg received its world premiere at the Royal Court in 1994, and he once wrote that much of the strength he needed to get well again was drawn from the knowledge that Reg was about to be staged for the first time.

"It was clear that he was still tremendously looking forward to his play being here," says Hastie of the show, which stars Julian Ovenden and is the first London revival since the Royal Court production.

"And in the last conversation I had with him a week before he died, he said he was still very excited." Last conversations are a recurring theme in the play. "Sometimes the poignancy is almost unbearable," says Hastie.

Although written in the early Nineties, Reg is set in the mid-Eighties. Guy's friends are visiting partly out of nostalgia for their university days but also as a kind of emotional refuge from the tyranny of HIV. Most have slept with (the unseen) Reg who, it emerges, had the virus at the time.

Hastie and I are sitting on a three-seater pink sofa shot through with gold thread, which will take centre stage in the production. "I'm not sure that it will look like this on opening night," says Hastie of the sofa. I say that it is hard to imagine a more appropriate piece of furniture. And although Hastie laughs generously, something tells me that by equating pink furniture to Elyot's characters, I've deployed a glib trope about gay people – the kind of cliché that probably drove Elyot nuts and which good directors prefer to avoid.

"It has the drawing-room comedy in its DNA," says Hastie focusing on the play's antecedents. "It knows it's coming from Coward, Rattigan, Wilde. But it's also Chekhovian in the sense that almost everything that happens, happens outside of the play."

Hastie could have just easily pointed to a Chekhovian sense of longing and the Chekhovian theme of unrequited love that informs the work. In that sense the gayness of Reg is its least interesting quality.

"The notion of Kevin being a 'gay playwright' instead of just a 'playwright' would have annoyed him," says Hastie. "What is striking about the play is that it isn't about being gay and it is isn't about Aids."

Still, around the time it transferred to the West End, My Night with Reg would have been exactly the kind of play the Evening Standard critic Milton Shulman wanted to see less of when he wrote an article in 1994 with the headline "Stop the Plague of Pink Plays". At that time the word "plague" was the preferred tabloid term for HIV. So to link plays that featured gay men with an epidemic that was killing gay men – implying that both the plays and plague were a comparable scourge – was, at best, crassly insensitive. It would be a little like complaining about Holocaust plays "goose-stepping" into the West End.

For playwright Martin Sherman whose Holocaust play Bent (1979) revealed the particular treatment meted out to gay men by Nazis, even the term "gay play" can grate. "I'm far more upset if a play like Bent is called a gay play than if I'm called a gay playwright," he says speaking from his Holland Park home. "Because I am a gay playwright. But Bent is more than gay. So is My Night with Reg."

These were plays that were written against the background of, as Jonathan Harvey puts it, "Laws that discourage you from being gay." Harvey, whose play Beautiful Thing was one of those attacked by Shulman, acknowledges that there was a campaigning impetus to plays that featured gay people. "I was writing with homophobes in mind as well as homosexuals," he says. In the age of gay marriage and divested of their campaigning impetus, the most compelling reason to revive the best of the "gay plays" of that period is not their gayness, but their humanity.

Yet when you think that in 1966, almost three decades before Shulman's article, the New York Times critic Stanley Kauffmann called for gay life to be "as freely dramatised as [is] heterosexual life", the integration of plays depicting openly gay characters on to the mainstream stage has been less than smooth. Two years after Kauffmann's call – and a year before America's Stonewall riots – Mart Crowley's off-Broadway play The Boys in the Band made the breakthrough. However, Kauffmann appears to have argued from the premise that gay playwrights such as Tennessee Williams had hitherto concealed gay sexuality in their work – a premise with which Tony Kushner disagrees.

"The Glass Menagerie is very close to being an openly gay play," says Kushner, author of Angels in America, which has the subtitle A Gay Fantasia on National Themes. The work is considered to be the greatest contemporary play depicting gay life. As with Reg, HIV is hugely present, albeit within a sprawling, highly political epic, as opposed to the contained one-room set of Elyot's play.

"No one has seen The Glass Menagerie and not had the sense that here is homoeroticism," adds the twice Oscar-nominated screenwriter of Munich and Lincoln. "And of course Streetcar is a play about many things, one of which is that Blanche has married a gay man."

Harvey says that Angels, which he saw at the National not long before Beautiful Thing received its premiere at the Bush in 1993, had a huge impact. "Overnight, I started to think about my own mortality. There is a moment in Angels where two men dance together. It was the most moving thing I'd ever seen in theatre. And I suppose that's what inspired the end of Beautiful Thing when the two lads dance."

The moment Kushner first understood the potential of plays with openly gay characters to affect attitudes happened outside the theatre.

"I was in high school and my father went to see the film of Terrence McNally's play The Ritz. He [Kushner's father] and I struggled a lot about my homosexuality. This was a time when he knew I was gay and really wanted me to make every effort I could to change it – by therapy, by dating women. And I was co-operating. But he came back from the movie and he volunteered to my mother that he had just seen 'a plea for tolerance for homosexuals and it's very moving'. That was stunning."

With lunch break over, rehearsals at the Donmar are about to resume. Carpenters are knocking together the French doors that feature in Elyot's post-drawing-room play. Hastie rises and looks back at the set.

"I think when we open, the sofa will be blue," he says.

'My Night with Reg', Donmar Warehouse, London WC2 (0844 871 7624; donmarwarehouse.com) 31 July to 27 September

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments