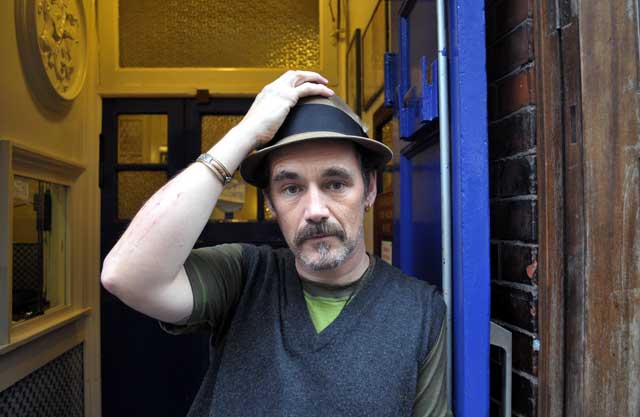

Mark Rylance: 'I'll play another woman'

This week's Olivier Award confirms him as the best stage actor of his generation – and he's got plenty more surprises up his sleeve

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I'm sure," says Mark Rylance, "that another actor will play that part and will play it wonderfully and differently and I would hope that the part will seem as natural to that actor as it seems to me." He's referring to the role of Johnny "Rooster" Byron, the vodka-swilling, drug-dispensing, ex-stuntman in Jez Butterworth's Jerusalem. Last Sunday, Rylance won the Olivier Award for Best Actor for the role of Byron. In his battle with the council over his right stay put in his caravan, this cross between Falstaff, Pistol and the Pied Piper represents a challenge to everything in our nannying, amnesiac culture that wants to pave over the past and chain us in nappies to focus-group-fostered conformities.

It may be some considerable time, though, before another actor steps into this already legendary stage-character's shoes. This is not just because Rylance is now indelibly associated with the part, but because he effectively co-created it. The Rylance spirit not only informs his terrific performance but also helped bring Johnny to birth. Rylance is the man who once took his own production of The Tempest on a rain-swept tour of ancient sites on ley lines. He's the figure who, as first artistic director of the Shakespeare Globe, renewed traditional practices that he felt had needed a fresh lease of life. That same principled caution about the idea that "progress" is necessarily a boon will characterise an evening of poetry and prose (on 18th April at the Apollo Theatre, featuring Michael Gambon, Kevin Spacey and Sinéad Cusack) that he has organised in aid of Survival International, a charity that campaigns for the rights of indigenous peoples.

Last Sunday's Olivier Awards administered some sharp sharp shocks. Jerusalem, thought to be a shoo-in in the Best Play category, lost out to an American drama about Martin Luther King. By general consent of the cognoscenti, however, this upset paled in significance compared to another complete inversion of expectation. Accepting the Best Actor award for his terrific performance as Johnny, Mark Rylance gave, for once, a largely conventional acceptance speech. He normally likes to ruffle the smooth, air-kissing self-congratulation of these occasions either through wacky mischief or through pointed political protest, as when, after receiving a Special Evening Standard Award for the collective achievement of the Globe in 2003, he brandished a copy of the previous day's paper and managed both to castigate his hosts and inveigh against the arms trade.

But then he's a committed political animal. As talented on screen as on stage, he conveyed in his Bafta-winning portrayal of Dr David Kelly in The Government Inspector a microscopic sense of the hunted and the haunted beneath the mask of containment. And it's said that he fell out with the chairman of the Globe's board because of his voluble opposition to the war in Iraq and the theatre's Season of Regime Change that coincided with the start of the hostilities.

Born in 1960, he is the son of English teachers who moved the family to the United States. Because his father taught at the University School of Milwaukee, Rylance got a precocious early grounding in all of the theatre arts (from set construction to lighting design) and was able to have his initial stab as Hamlet in a production in which his father was the First Gravedigger. So he has always known his mind and distrusted institutional orthodoxy. Matthew Warchus remembers that they had a "turbulent relationship" on Much Ado About Nothing until the director convinced him that he saw his own role as being "the hub of the wheel rather than the top of the ladder". A stabilising and professionally enriching force in his life is his long, happy marriage (since 1992) to the composer/musician Claire van Kampen with whom he has reared two stepdaughters, one of whom, Juliet, has been playing Miranda to Stephen Dillane's Prospero in Sam Mendes's Bridge Project Tempest.

I first interviewed Rylance in 1994 and over the years this slight, gently voiced, quietly visionary figure has often struck me as being almost like a visitor from another planet where they are more human than we humans. His acting, whether in the Bard or in other modes of drama, bears out, in its uncanny openness to the ways in which seriousness and absurdity stalk each other, the truth of what Dr Johnson said about Shakespeare, "His tragedy seems to be skill, his comedy to be instinct". And in his approach to experience, Rylance is the very embodiment of Peter Brook's belief that the point of life is to be like "a child but with experience". It seems never to have occurred to Rylance to stop asking the kind of deep philosophical questions that children instinctively pose or to permit suffering to sour his sense of wonder.

His next West End project will be a revival of La Bête, a neo-Molière rhyming-couplet comedy about the battle between high and low art (in which he will star with Joanna Lumley and former Frasier star David Hyde Pierce). We also discussed when we can expect him back playing in Shakespeare – whose authorship of the plays he fervently disputes – at his old kingdom, the Globe.

At a preview of the West End transfer of Jerusalem, I noticed that, at the fourth curtain call, Rylance jumped in the air. Was this, as it looked, for joy? In the play, Johnny is last seen soaked in blood from a vicious reprisal and beating a drum to summon giants who are not going to be able to save him from being lynched. "If it goes to a fourth curtain call, I do jump for joy because, by then, there is a such a sense of liberation that we have survived the dark place that we have all of us – actors and audience – just explored. I think there is a sense of birth at the end of a good tragedy." He likens his jump to the traditional jigs he revived to round off tragedies at the Globe: "The pounding of the floor was like the smack that awakens a baby, a way of bringing people back to this world and a completion not a contradiction of the play you'd just seen."

Every night before the show, he and the whole company, including the technicians, meet in the stalls of the Apollo Theatre (which are conveniently divided with a central aisle) in order to play a fast game of volleyball. "It's sport but it absolutely wakes up what you need on stage – a reminder that this is not television or the movies and that people are paying for us to be live. They don't want yesterday's performance. They want now."

Ian Rickson, the director of Jerusalem, says that, with Rylance, "there is always something very special in terms of rhythm. He's able to give his inner life so fully to the world of the play that, when you watch, something strange seems to happen to your sense of time, as though he has suspended it. There's also that male/female balance that you get in great artists such as Fiona Shaw and Frances de la Tour". Or – a parallel that has struck me – Johnny Depp.

When I asked Dominic Dromgoole, Rylance's successor at the Globe, how he'd describe Rylance as an actor, Depp was one of the other performers he invoked: "There are very few actors who can combine complete clownishness with leading-man charisma and they are the icons of the modern acting era – Johnny Depp, Daniel Day-Lewis, Jim Carrey and Mark".

Another dichotomy pointed out by Warchus who will direct him in the forthcoming La Bête (a regular collaborator since he directed his brilliantly left-field Ulster-accented Benedick in an early-Nineties Much Ado) is the conflict between outsider and insider. That's one of the themes explored in La Bête, in which Rylance will play a vain, endlessly digressive (one of his speeches lasts 25 minutes) but vividly vibrant troubadour who is forced, by royal edict, on the official court troupe.

Talking to Rylance, you feel the quiet force of his authority-questioning personality, whether it be on the Shakespeare authorship controversy, say, or on moral matters outside of the theatre. On the former, his views are of a piece with his sense of theatre as an inherently collaborative medium and tie in with what he tells me about the creation of Jerusalem. "If you hadn't asked me, I wouldn't have spoken about it today and I want you to write that," he insists. "It's not a subject that I harangue people on." He recoils from "the idea of the single, solitary genius because it's very damaging to the confidence of young playwrights today". And it fails to accord with his personal experience on plays such as Jerusalem. As Ian Rickson confirms, Rylance's impact on the Butterworth hit was crucial. The actor was initially attracted to an early draft on account of its title St George's Day and his interest in the St George legend. This in turn inspired Jez Butterworth who seems to have absorbed Rylance to the point of being able to "channel" him.

Rylance explains something of the subsequent working method: "Ian would say to me that 'at a certain moment, I am going to ask you to go off text and then I want you to just improvise and go wherever it takes you'. And at the end, Jez would say 'I understand it now'. He wouldn't write what we had improvised but the scene would be different because of this very raw style of collaboration."

Rylance's own collaborative play I Am Shakespeare was anything but a po-faced piece of proselytising. He was on hilarious form in it as a nerdy obsessive who ran a daily webcam show in his garage, which, after a freak lightning storm, was invaded by Shakespeare and the rival contenders – Bacon, the Earl of Oxford and the Countess of Pembroke. In so far as the play can be said to agree at all with Contested Will, James Shapiro's new, respectfully sceptical book about the psycho-biographies of the anti-Stratfordians, that, as he puts it, "in searching for the author, you end up actually revealing a lot about yourself".

The irony, as Warchus (who directed the show) remarks, is that Rylance is pretty much how most people would like the Stratford man to have been. That's one of the reasons why we need him back on the Globe stage. He's vowed not to do the Bard anywhere else and Dominic Dromgoole is ready and waiting. There's a distinct possibility that he may return to play Richard III. The man who has already portrayed a theatrically skittish Cleopatra and gliding geisha-like Olivia also confesses that "I would like to play another woman". I would love to see him as the contradictory Paulina (half severe goad to penitence, half warmly caring protector) in The Winter's Tale. That would be piquant indeed.

Jerusalem, to 24 April, Apollo Theatre, London; La Bete, 28 June to 28 August, Comedy Theatre, London

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments