Mark Gatiss on summoning the ghost of John Gielgud in The Motive and the Cue: ‘It’s the best part I’ll ever get’

Mark Gatiss gave one of the performances of the year as John Gielgud in ‘The Motive and the Cue’, which took audiences back to his infamous 1964 Richard Burton ‘Hamlet’. He talks to Sarah Crompton about Gielgud and Olivier’s rivalry, great actors and alcoholism, why he no longer watches the news, and the possibility of a return to ‘Doctor Who’

Mark Gatiss sits in his dressing room at the Noel Coward Theatre and looks around. “He possibly sat here. It’s quite strange,” he says, with a look of wonder, as if he is feeling the presence of a ghost.

He is talking about John Gielgud, one of the great knights of 20th-century British acting, and who Gatiss is about to play for the second time. Many felt he truly summoned Gielgud’s ghost in his performance. Having opened to rave reviews at the National Theatre in the spring, Jack Thorne’s The Motive and the Cue now transfers to the West End – and to the playhouse originally known as the New Theatre where, from 1933, Gielgud was manager. In November 1934, he played Hamlet here, in his second go at the role. It ran for 155 performances.

In The Motive and the Cue, though, Gielgud is not playing Hamlet but directing it. Thorne takes audiences inside the 1964 rehearsal room for his infamous Broadway production starring Richard Burton, just after Burton had married Elizabeth Taylor (played here by Johnny Flynn and Tuppence Middleton). The show became the stuff of legend, generating a frenzy of excitement that led to a record-breaking run.

Directed by Sam Mendes, Motive explores a combustible mixture of fame, bruised egos, and different generations of acting style and talent. At its heart is Gielgud, whom Gatiss plays with a tender sensitivity. “I think it’s the best part I’ll ever get,” he tells me, simply. “There’s something interesting about that in terms of what on earth I do next.”

But for now, the Sherlock and League of Gentlemen star is enjoying the experience. “I really love him, and I love the fact that there is so much affection for him and so many stories – most of them probably apocryphal. The other day, someone wrote to tell me one I’d never heard, about Gielgud trying to jump on a bus. It started to go when he wasn’t quite on and he shouted at the driver, ‘Don’t you know you’re killing a genius?’”

He laughs with pleasure at the story and admits that some of Gielgud’s mannerisms have sneaked into his daily life; his impersonation of his voice, with its descending falls, is uncanny. “I’ve been quite glad of a break from playing him, because although people go on about taking parts home with them, some of it is inevitable because it’s a rhythm.”

He now shaves his head every day to look more like Gielgud, but he admits he has been taking off that voice ever since he was a kid, impressed with the great man’s performance in films such as The Elephant Man and Murder on the Orient Express. He quotes chunks, in those melodious tones.

“I never saw him on stage, alas, but I was very aware of him growing up as part of that triumvirate of greats – along with Laurence Olivier and Ralph Richardson. I’ve found out a tremendous amount doing this play, which I didn’t know. Mostly around the fact that although Richardson and Gielgud were great friends, Gielgud and Olivier really didn’t get on. I knew there was rivalry, but it’s not very nice actually and Olivier doesn’t come out of it very well.

“Eventually what lasts is kindness and people remember Gielgud very fondly for all kinds of reasons. He was very funny, very mischievous and very kind. Whereas Olivier was ruthless and long after he was gone it leaves a different taste.”

Gatiss talks about watching a documentary in which Trevor Nunn interviewed actors about their different versions of Hamlet, filmed near the end of Olivier’s life. “Olivier is not well but even though he is fragile he is still having a go at Gielgud about his singsong voice, and you think, god it’s still there, this strange sort of enmity. But then again, when they were rehearsing Othello, Gielgud said to Peggy Ashcroft” – he slips into the voice again – “‘I’ve never felt jealousy, I don’t know how to play it.’ Then he added: ‘Oh I remember. When Larry got good notices for his Hamlet, I wept for three days’.”

Gielgud and Olivier really didn’t get on. I knew there was rivalry, but it’s not very nice actually

The anecdote, burnished with the impersonation, reveals Gatiss’s deep love of theatre history. The play has proved a perfect vehicle for his interests, with people who knew Burton and Gielgud popping in with stories and memories. They include Richard L Sterne, the actor who played a gentleman when he was just 20 and whose record of the production provided part of the inspiration for the play. “He’s seen it three times,” Gatiss declares. “It’s been very special for him. In the play, another character says, ‘I just want to be part of something that will live for all time.’ And the extraordinary thing for Richard is that he was.”

Brian Cox, who was in Gielgud’s Julius Caesar, and Sian Phillips are among other actors who have come to see the show. “It’s brilliant and interesting to have that kind of blessing.” Ian McKellen asked why Gatiss’s Gielgud doesn’t smoke, when in life Gielgud was a chain smoker. “In a funny way, making Burton [played by Johnny Flynn] the booze and fags man made me more ascetic,” Gatiss explains. “There’s a scene where Burton brings in drinks for the whole cast; in fact, it would have been no means unusual for people to have a drink when rehearsing but we can’t present that now because we have to look at it in a different way. It’s a play. It’s a story organised in a way that real life isn’t.”

On which subject, McKellen also remembered giving Gielgud a lift home – and having to wind down the windows of his Mini afterwards because his halitosis was so bad. Burton, for all his glamour, drank and smoked so much he must have smelt. Gatiss remembers reading a book called Hellraisers about Burton, Peter O’Toole, Richard Harris, and Oliver Reed, all legendary drinkers and roisterers.

“If you read individual anecdotes, it’s so funny but collectively it is so depressing. There’s an anecdote about Burton going for an X-ray on his back and it was like a Christmas tree because his spine was covered in crystallised alcohol, like a fir tree. The surgeon told him he would be dead in 10 years if he didn’t stop drinking. He was dead in 12.”

The fact of Burton’s early death at the age of 58 prompts a gasp at the end of The Motive and the Cue. It is a tribute to the play that it has managed to appeal to audiences who aren’t obsessed with theatrical history as well as those who are. “What they get, I guess, is these two titanic figures having a battle of wills and then finding this moment when they come together. It’s very moving even if you don’t know the details. It transcends the facts.”

Is there, in any case, a danger of romanticising the actors of the past? Gatiss thinks for a moment. “It’s the myth of the golden age,” he says, thoughtfully. “There’s always been great people, there’s always been terrible people. Those actors have an amazing legacy. Gielgud says in our play: ‘Theatre for me has been a life.’ That’s a commitment. It’s not just popping in and out.

“He just did so much. There is something genuinely magical about the fact that they just used to put a show on for three and a half weeks and then another one. There is something brilliant about that white heat of industry which means that in among it all of course they produced great art but maybe that wasn’t their intention. They were just doing stuff.”

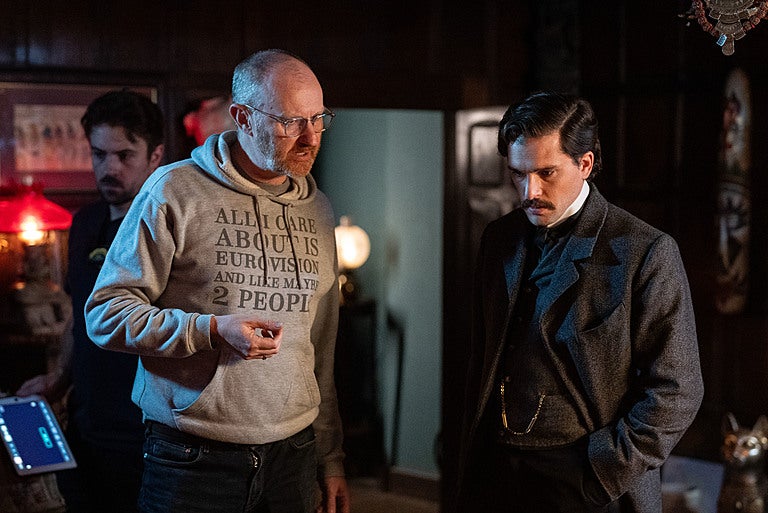

Gatiss himself is currently embroiled in the white heat of industry. He has written a version of A Christmas Carol, which has just opened starring Keith Allen at Alexandra Palace. On BBC on Christmas Eve there will be what is now becoming his traditional – “it’s my sixth” – Ghost Story for Christmas in the shape of Lot No. 249, an adaptation of Conan Doyle’s short story about a mummy’s vengeance, starring Kit Harrington, Freddie Fox and Colin Ryan. “I think it might be my favourite one,” Gatiss says, with a grin.

“Ghosts are my favourite thing and I’ve always loved Christmas too, and the two go together like chocolate and orange. At the end of the year, you are looking backwards and forwards, and I’ve always thought that if anyone is going to come back, it would be at Christmas. There’s something about the thinness of the end of the year, when a lot of those things feel more possible.”

But the major “insanity” of additional work, is that at the same time he is on stage in The Motive and the Cue, he is also directing The Unfriend, a riotous comedy about an unwelcome guest, by his real friend Stephen Moffatt, which is about to transfer to Wyndham’s. This is literally the theatre next door and connected by a passageway across an alley, so technically speaking, Gatiss can run from one to the other without anyone seeing him. But since both shows are on stage at the same time, after rehearsals have ended, he will only be able to see it at its first matinee.

My partner said that the house was looking very tidy. I pointed out that was because we were not in it

“I would like someone to find out if it has happened before in adjacent theatres,” he says, with another quick laugh. “I’m not physically tired. Gielgud did this. Lots of people did – direct a play in the day and then do a show in the evening. I am not knackered. But there are just not enough hours in the day, and all kinds of little things get away from me. My partner is doing panto, so we meet at night in the dark essentially to have a brief chat. He said today that the house was looking very tidy. I pointed out that was because we were not in it.”

Mention of his husband Ian Hallard draws attention to the way things have changed since Gielgud’s day. Gielgud was gay at a time when homosexuality was illegal, and was convicted and fined for cottaging – an incident briefly referenced in one of the most moving scenes in The Motive and the Cue. He lived most of his life hiding his sexuality. Gatiss, on the other hand, proposed to Ian on the afternoon they met.

“It is a long time ago and in a different world but it is also very close,” he says thoughtfully. “These rights are massively under threat. I was watching a video about a raid in Russia and Putin’s new laws making LGBT+ groups extremists. It’s 500 miles away and it’s happening now. It’s both a long time ago and very much not.”

The harshness of today’s world is one reason Gatiss finds he cannot any longer listen to the news. He shuts politics out. “I’m afraid so. I just can’t bear it. As a child, I used to listen to the Today programme through my parents’ bedroom wall and I remember when my dad retired, he stopped listening. I totally understand that now.

“I cannot watch the news or Question Time. It saddens me because I used to love the cut and thrust of politics. But there are no rules anymore and it’s frightening. You can’t take any pleasure in a Tory leadership contest when there have been five in five minutes. It’s frightening because all those certainties, and the idea that there were people who knew what they were doing have gone. I can’t look across the Atlantic, because it’s too terrifying to contemplate.”

I used to love the cut and thrust of politics. But there are no rules anymore and it’s frightening

He has, however, found time to watch the most recent instalments of Doctor Who, a series with which he has been closely associated as a writer and actor. “I absolutely loved it. I think Russell [T Davies] has got such an unerring grasp on the show as a popular hit. It was an absolute masterstroke to bring David Tennant back because he is the Tom Baker for a whole generation. So for the anniversary year, it refocuses it through three wonderful specials and here’s the new guy and off we go.”

Would he be part of it once more, I wonder? He tells the most wonderful story that has echoes of the moment in Sunset Boulevard when the fading star Norma Desmond is contacted by the film studio. She thinks it is because they want her to make her comeback. In fact, they are after her car.

Gatiss received a telephone call the other week. “It makes me howl with laughter,” he says. “I thought maybe a script had fallen through and it would be ‘you’re the only man who can save us’. Then the script editor asked if they could borrow Jon Pertwee’s smoking jacket which I own.” He laughs again, and then adds, in a deliberate parody of Norma’s most famous line, “I told Russell: I am big; it’s the Tardis that got small.”

The Motive and the Cue is at the Noel Coward Theatre until 23 March, 2024

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments