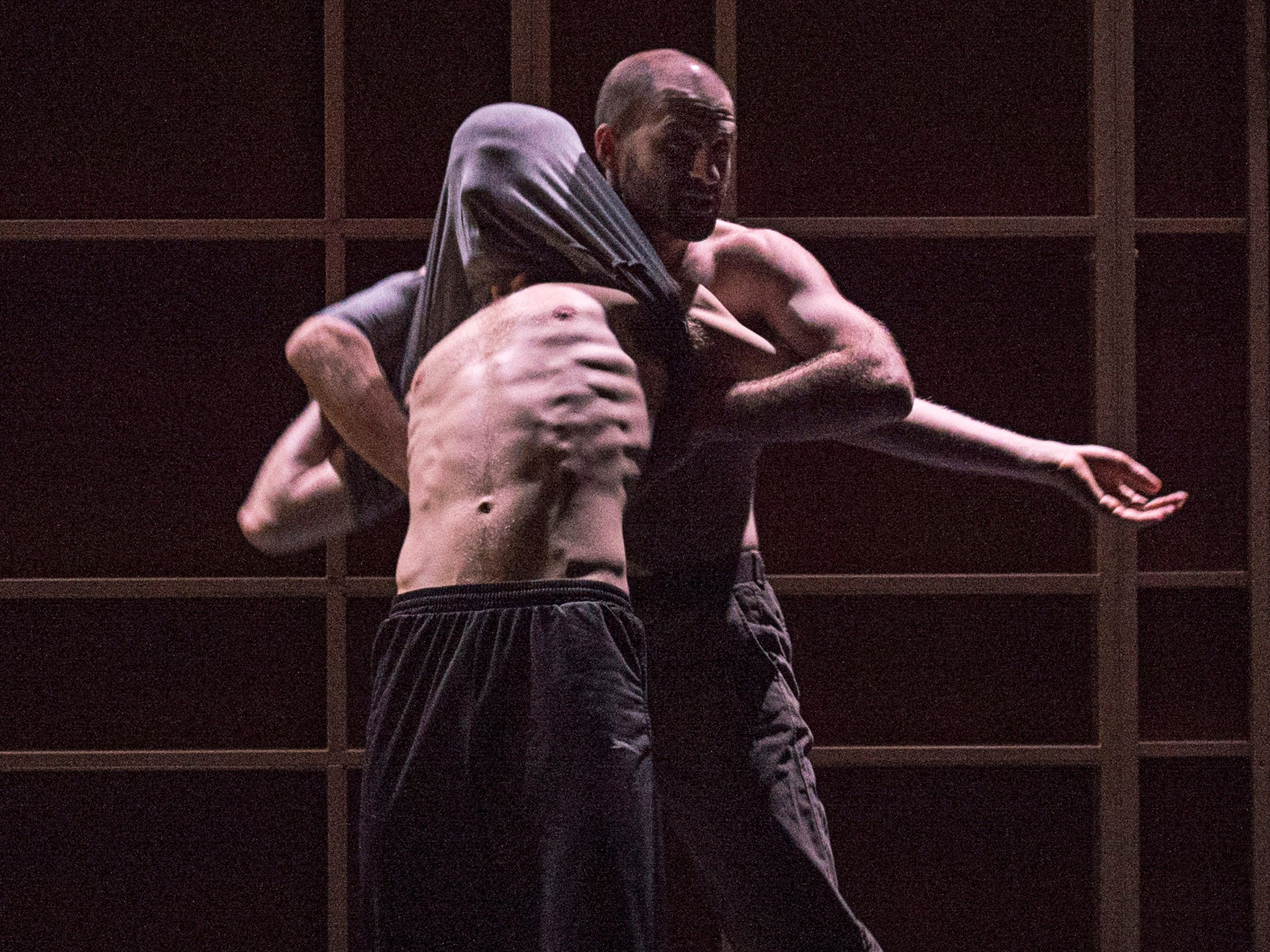

DV8: Three decades of the provocative dance-theatre company

Ahead of the premiere of their new work ‘John’, director Lloyd Newson talks busting taboos and giving movement meaning

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In a rehearsal studio in east London, I have met Lloyd Newson, the pioneering artistic director of dance-theatre company DV8, to discuss his latest piece John, opening at the National next week.

But wherever the conversation turns, it keeps straying back to his previous work, Can We Talk About This? There is, clearly, still lots to talk about concerning the searing 2012 production which addressed what Newson perceived as Britain’s liberal blind spot with regard to radical Islam.

It was certainly one of the more contentious theatrical experiences of recent memory; critical commentary ranged from “extraordinarily brave” to “a Melanie Phillips column turned into a dance performance”, while Newson lost friends in the making of it. But with the recent Rotherham abuse and “Trojan Horse” schools scandals, Newson feels vindicated in his thesis. “What we raised in [that piece] has only been proven to be correct,” he says. “In the past two years we have seen [the effects] of turning blind eyes to certain cultural/religious practices. It has not helped social cohesion, which is what we all want … in fact, ironically, politicians have created the very problems they were trying to avoid,” he says.

One thing’s for sure: from its title onwards, Can We Talk About This? encapsulated the frankness that has made the Australian-born choreographer and theatre-maker, and DV8, such scintillating creative forces over the past 28 years. “The things people say we cannot look at and talk about, I say ‘why not?’,” as he puts it. Such candour has been both physical – in the fierce, fearless action of the company’s early movement-centred works – and verbal, as his pieces have become increasingly text-based.

John sounds less obviously controversial than his last two, polemical works, Can We Talk About This? and To Be Straight With You, but, you suspect, it will be no less hard-hitting. Like those shows, it is a verbatim theatre piece: the starting point was a desire to explore men’s relationship with love and sexuality, which Newson did by interviewing a range of men who went to gay saunas. It was a locale he chose for its potent ambiguity, he says. “It felt like a very fertile ground [from which] to say to people: what is the relationship between love and sex [for you] … why do you come here? Is it only about sex? Maybe it’s about something else, maybe it’s really for love, [or] maybe it’s about neither of those things.”

But the piece came into focus as soon as one particular man, the eponymous protagonist, entered the interview room. John, 52, was a man seeking to reconfigure his life, in more ways than one. A working-class Northerner, son of an abusive father, his life thus far had been a catalogue of criminality, drug addiction and homelessness. Five weeks out of jail at the point Newson met him, he was living in a probation hostel and seeking to reform – “at one point he said to me I want to be ‘normal’ the way you middle-class people define ‘normal’” – while at the same time searching for his first proper relationship with a man, having had girlfriends all his life. “Will [John] change? Can you change? Do we trust people to change? Does he trust himself? ... there are all those questions,” says Newson.

While Newson classifies the piece as personal rather than political, it’s clear that such a narrative has resonance at a time when social mobility is going disastrously backwards. And as he speaks of John’s “honesty”, the kind that rubs up against the middle-class “code of behaviour where you don’t always say what you think”, it’s also clear that Newson, a miner’s son who has always disregarded arts-world niceties, strongly identifies with John in this respect. Newson may have an OBE and be embraced by the National Theatre these days, but don’t use the E-word: “Talk with anybody who deals with me and [they’ll say] I’m so anti-Establishment,” he protests

Nevertheless, meeting Newson, you feel the “provocateur” tag short-changes him; rather, he is as judicious in speech as he is opinionated, and extremely sensitive to nuance. He asks me to refrain from describing one particular detail of the production, lest it come across in print as sensationalist. And he is extremely wary of John being ghettoised as “a gay piece”. After all, “there are all sorts of questions which come up that have nothing to do with being gay”, he says, and not all gay men will be happy with it, in any case, he expects, because its treatment of gay sexuality doesn’t fit with the new, romantic, “white wedding” narrative. “A friend of mine asked me is it really time to be doing this piece? [But] that’s what people said when I did a piece on Islam and free speech.”

As for the movement, well, expect it to be as arresting as ever. This is a man who has talked of dance as “the Prozac of the artforms”, for what he sees as its vacuous, anaesthetising beauty; he sums up his own approach as “if people don’t understand what’s being said physically, I’m not interested”. It is this rigorous attitude to meaning that has led him to centre his work on verbatim speech in recent years – and in turn, working with ever more dense and naturalistic text has made him a better choreographer, he says. “It forces you try to find a movement that will match what is being said, and the array and combinations of words is endless, so it’s made me more particular – and of course there are no pirouettes or arabesques because they’re absolutely meaningless.”

Beyond John, meanwhile, expect Newson to keep up the taboo-busting. One idea he has is for a piece about death and assisted suicide. “I think it’s extraordinary that when the Government’s telling you to be in control of your life, the one thing they won’t let you control is your death,” he says. “There might be something interesting in the fact that there are people who are now going to Dignitas because they are ‘life tired’. Are we ready as a society yet to acknowledge that some people have the right to end their life even if they don’t have a terminal illness?”

Given his zeal, would he ever engage in politics directly, I wonder? “Oh no, politics is hid-e-ous,” he says, wincing. “I think I’ve been much more honest as an artist than I ever could be as a politician.”

‘John’ is at the NT’s Lyttelton Theatre from 30 Oct to 13 Jan, then tours until 13 Mar. It will be broadcast to cinemas worldwide as part of NT Live from 9 Dec

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments