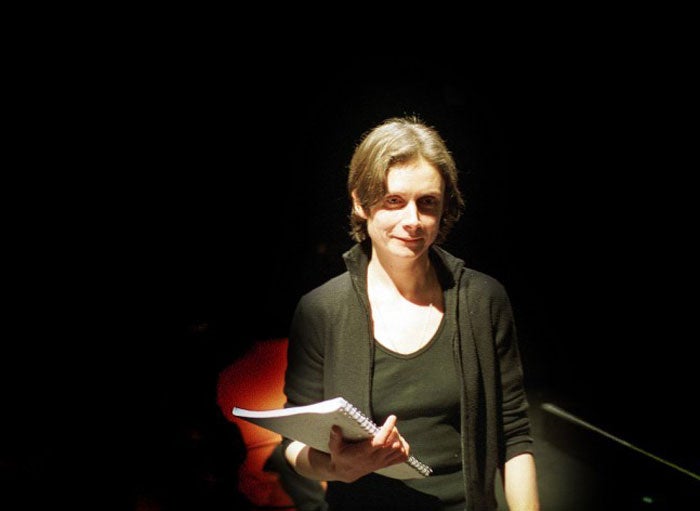

Katie Mitchell: 'I'd hate to hang around making theatre when they're tired of it'

Theatre director Katie Mitchell's work has horrified many critics – but others love her plays. She tells Alice Jones how she thinks her latest venture, 'The City', will be received

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Katie Mitchell is sitting in a draughty church hall in south London rhapsodising about a surprisingly glamorous formative influence. "I used to love watching Come Dancing," she says, starry-eyed, her half-eaten sandwich poised in mid-air. "All those women in amazing frocks with fluffy yellow frills. At its heart, it's such a beautiful metaphor for men and women together." By the time these frills and footwork have undergone the Mitchell treatment, of course, they are largely unrecognisable: think of her coquettish foxtrotting chorus in Iphigenia at Aulis, her mismatched, passionless couples doing the tango in The Seagull and, most recently, her bereft women of Troy dancing a frenetic, desperate quickstep with only the ghost of their partner to guide them.

Depending on where you stand in the Mitchell debate – and she is a director who polarises audiences like no other – her relentlessly innovative approach to theatre either dusts off the classics, bringing them back to the stage with a spring in their step or it trips them up with clumsy rewrites and clashing anachronisms. "It's very curious that people so hate one thing, so like another," she shrugs. "But you can't tell people how to receive your work, can you? That would be consummate arrogance."

Her latest project is directing Martin Crimp's new play The City at the Royal Court. Crimp and Mitchell are an established double act, having collaborated on both his plays (most recently, Attempts on Her Life) and his versions (The Seagull) over the last decade. They make an intense if odd couple – she a diminutive bundle of precisely focused energy, her short, grey-flecked hair scraped back from piercing eyes and cheekbones, he a rake-thin, wraith-like figure, hiding behind a smooth curtain of white hair. They work together "hand in glove", says Mitchell, who even has to have a whispered consultation with the playwright before she allows herself to answer my first, basic, question. "What's it about? Failure of imagination. Sex. And employment." Right.

Crimp is famously protective of his work, refusing to release scripts until opening night and indeed, when I arrive at the rehearsal rooms five minutes early, I am quickly asked to leave and wait outside lest I overhear a precious fragment. So it may or may not be a companion piece to The Country, Crimp's sinister, cryptic three-hander about a married couple who move to the country to escape their demons, which Mitchell directed at the same theatre in 2000.

For The City her long-time designer Vicki Mortimer is on board again as is Hattie Morahan, who played Nina in The Seagull and Iphigenia. The 43-year old director prefers to work with a tried-and-trusted family. "You waste a lot of rehearsal time learning someone and sharing with them how you want to work," says Mitchell. "I'm quite a shy person and I find that stage of getting to know a collaborator quite agonising, like being at some awful cocktail party."

Benedict Cumberbatch and Amanda Hale (a wonderfully nervy Laura in The Glass Menagerie) are both new to the rigorous Mitchell method. Kate Duchene, Hecuba in Women of Troy and a frequent face in the director's casts, recently agonised in an interview that if she became "a Katie Mitchell actor", all other directors would be "scared" of her. It's true that Mitchell is the closest thing the British theatre has to an auteur. "I find it quite hard that I give the impression of such a strong personal signature," she demurs. "That's not my intent."

Though it wasn't much talked about during her Berkshire upbringing – "I don't know why, perhaps it was a class thing" – theatre is in Mitchell's blood. Her great-grandparents met in the music hall. She was a Tiller girl and he worked with Charlie Chaplin and Fred Karno. "He went on the South African tour but then he was forced by my great gran not to go on the American one so he missed all the success and became a bookie instead."

Mitchell directed her first play, aged 16, at Oakham School. In a typically audacious move, she reconceived Harold Pinter's little-known radio play Family Voices for the stage, as well as playing the piano and acting in it. She went on to study English at Magdalen College, Oxford, and threw herself into the university's drama scene as well as gorging on the work of the avant-garde – from Hesitate and Demonstrate to Pina Bausch. Her first job was stage managing and working in the kitchen at the King's Head Theatre Pub in Islington, London, before she became an assistant director at the experimental Paines Plough and the RSC and travelled around eastern Europe, learning from the great theatre practitioners Lev Dodin and Tadeusz Kantor. In the early 1990s, she set up her own company Classics on a Shoestring and was eventually made associate director at the Royal Court and the National.

With such an eclectic background, it's no surprise that her career has always leapt between extremes – from the classics to brand new; from straight ensemble acting on a bare stage lit by candlelight to hi-tech multimedia extravaganzas such as Waves and Attempts on Her Life in which live action is filmed in close-up by the actors and projected on to video screens. Although the latter direction has caused its fair share of huffiness amongst theatre purists, it is Mitchell's bashing around of the classics that has made her name.

"Bash them around is a bit cheeky, isn't it?" she says. "I cut them, let's say, with careful consideration without dismantling the idea structure that is at the heart of the play. People think I might be wilful in some way with the material but no – my aim above all is clarity. They think it's 'oh, let's just throw it all together in this irresponsible, anachronistic fashion and see what happens.'"

She's still smarting from the reaction to The Seagull in 2006 – critics groaned at its inconsistencies and one particularly disgruntled punter posted her a programme with "RUBBISH!" scrawled across it. "It was surprising. In retrospect I can see where I made the errors. But I bet you, even if I had corrected all the things which weren't clear, I'd still have got the same reception for it," she sighs. "I felt that Chekhov had almost been adopted into the family of British theatre. He'd become almost equal to Shakespeare. But it did obviously really offend and I genuinely didn't intend to."

The vociferous reaction rumbled on into last year when Nicholas Hytner, the artistic director of the National, singled out – wrongly – Mitchell's work as the victim of "misogynistic reviews" in his diatribe against "dead white male" theatre critics. "I felt incredibly supported by him but also a little exposed. If anyone were to take the comment amiss, I'd be a natural target for their upset." But where she shrugs off the importance of her gender, she is more forthcoming about the changes that her two-year-old daughter, Edie, has wrought on her work. "It's like someone has removed a layer of skin so you're so much more vulnerable." Has motherhood made her a better director? "I suppose I'm privileged to understand a lot more about human experience. I've watched someone die once – my dear granny – and I've never recovered from that. And I can't recover from having a baby. How you understand the world changes. And I punish myself so much now about how I didn't understand actors who had families and who didn't want to rehearse 24/7."

There's no let-up for Mitchell though. Next is ...some trace of her at the National, a multimedia piece inspired by Dostoevsky's The Idiot starring Ben Whishaw. She has just "boiled it down to 60 pages", a move not likely to endear her to those still smarting from her chopped-about Chekhov. But she is nothing if not ambitious and would love to direct a film, do a musical – "but no one would let me" – and create a children's show for Edie. "But I'd hate to be one of those people who still hangs around making theatre when they're tired of it," she says. "I'd rather go and work in a bookshop."

'The City', 24 April to 7 June, Royal Court Theatre, London SW1 (020-7565 5000)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments