Why are stories by or about queer women ghettoised as 'lesbian' or 'feminist'?

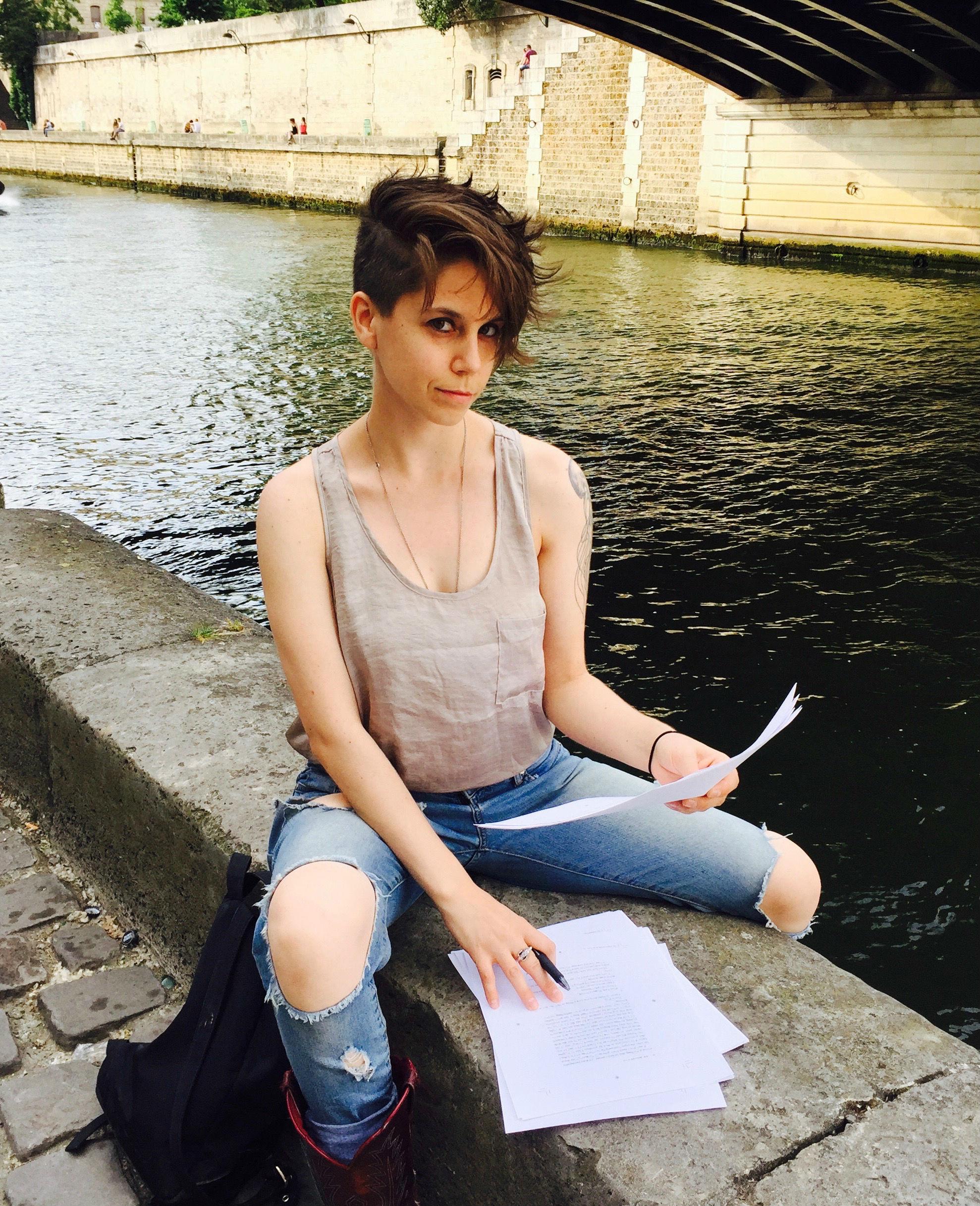

As the award-winning American playwright Jen Silverman’s unapologetically queer and female play 'Collective Rage: A Play in Five Betties' arrives in the UK, she looks at how gay women aren't reflected in the arts, but must place themselves inside work that was not made about them

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Let’s start with the title. My play is called: Collective Rage: A Play In 5 Betties; In Essence A Queer And Occasionally Hazardous Exploration; Do You Remember When You Were In Middle School And You Read About Shackleton And How He Explored The Antarctic?; Imagine The Antarctic As A Pussy And It’s Sort Of Like That.

Oh God, you say, what’s that about? (Or, if you’re my mother, maybe you say, “Do you have to use that word?”)

The play is about five women, all named Betty. Betty 1 is straight and upper-class, she’s always followed the rules yet finds herself furiously dissatisfied. Betty 2 is a sexually suppressed misfit, who longs for friends. Betty 3 is vibrant and bisexual, someone whose creative impulses aren’t fulfilled by her job at Sephora. Betty 4 is working-class butch, a loner afraid of change and too scared to tell Betty 3 that she loves her. Betty 5 is genderqueer, guarded, someone who uses sexual charisma to mask vulnerability.

All five women collide with each other, and as their view of each other shifts and fractures, so too does the way in which they see themselves. Eventually, through a series of escalating events (including a community theatre production of the Rude Mechanicals bits from Midsummer Night’s Dream) all five reimagine the world they want to live in, and the people they want to be. The play is an invitation to exercise a braver, more vital imagination about who we are and what we’re capable of; it’s a comedy based in desperate dissatisfaction.

I wrote the first draft of Collective Rage during a sweltering New York summer. When I walked home from the subway at night, men cat-called me. During the days, I found myself in liberal settings, where educated men talked over me. I kept wondering what these men saw when they looked at me that permitted them to dismiss my agency in such different but tangible ways? I could feel myself internalising this dismissal – dressing to ward off the cat-calls, or silencing myself before I could be interrupted.

Over the summer, the question shifted from: What are you seeing when you look at me? to: How can I unlearn this gaze? Maybe even: How can I destroy the shape I am becoming, beneath this gaze? From this, Collective Rage was born.

The title alone has made for self-selecting but passionate champions, as the play travels from American premiere, to publication, to UK premiere. It has also made for the opposite. And it has also encountered men who haven’t made it past the title. If it isn’t about men, how can it be for them?

This isn’t an essay about how queer women are underrepresented in literature and media, although the lack of queer protagonists and protagonists of colour is indeed a glaring problem in the US. (Diep Tran is one of the bright stars of American theatre journalism on this topic and others.) While I think it’s high time for us to see ourselves reflected in the cultural narrative – while I have argued elsewhere that, without seeing ourselves depicted, we are deprived of an entire language of identity – this is about what it means to locate yourself inside art that was not made about you.

I have spent the past year obsessively reading the novels of Richard Yates. Each is a slightly different angle on the same man: a depressed American searching inside himself for exceptionalism but not finding it, reconciling himself to his mediocrity in a country whose most pervasive self-myth is that everyone is capable of greatness. As a kid, I attended a small-town high school, where the intellectual templates laid out for my consumption were predominantly male and straight. I was swept away by Tim O’Brien’s story-collection The Things They Carried, despite the fact that the narrator was a soldier in Vietnam and I was a queer teenager in a conservative milieu. We were both trying to figure out how to name raw and unspeakable feelings, how to know ourselves with any certainty in unstable environments. Whether Richard Yates or Tim O’Brien, the TV show Mad Men or the paintings of Edvard Munch, I’ve found a deep and real identification with work that contains an urgent self-questioning, an interrogation of the cost of individual happiness. I see myself in work that doesn’t hold my reflection.

Women have been trained from the earliest ages to find ourselves in stories that were not written about us. We’ve had to do this, because otherwise we would have no stories at all. There is a particular muscle of empathy, of identification with others, that we exercise from childhood. I would argue that locating one’s self in the universality of stories that do not directly feature us, is a practice that makes for better artists, even better humans. Radical empathy enriches, it doesn’t impoverish. But here’s the sticky question: why are stories about straight white men seen as “universal”, and all other stories labelled “niche”?

Stories by or about queer women are ghettoised as “lesbian” at worst, “feminist” at best – narratives that have no bearing on the lives of men. Likewise, stories by or about people of colour are marked “ethnic” – the subtext for white audiences being, “Learn something exotic!” and not, “See yourself in this.” There is a deeply embedded if unspoken belief, in the US anyway, that straight white men cannot be expected to care about stories in which the characters don’t look like them. This strikes me as unbearably condescending, an ideology that robs them of the kind of radical empathy that the rest of us have (by necessity) spent our lives practising.

Let’s say you’re an artistic director, who prides yourself on programming new work. You have a “slot” for a female playwright so that your audience can see Woman Things. And you have a “slot” for a playwright of colour, so that your audience can see Ethnic Things. And the other three or four slots in your season are meant to be about universal human stories, and so that is where you put your Chekov, your Arthur Miller, your emerging white male playwright. You mean well, you really do. But why is this the dominating ideology, and why do we accept it, when it is reductive and culturally impoverishing for us all?

So now you know the title and the provenance of my play – and you know, or have guessed, that it is fiercely, unapologetically, joyfully queer and female.

Here’s something else you should know: if you are a straight man reading this and thinking, “This is not for me,” then you’re wrong.

I can’t promise that you’ll like Collective Rage. But I can promise: It is also for you.

This play is for you, because if you are human, then you know what it’s like to have someone see you in a way that limits you. It’s for you because, if you are awake in the world today, then you know what it’s like to want to imagine a different one. It’s for you because, if you’ve survived your teens, you know what it’s like to fall in love with someone in a way that shatters your ideas about yourself. It’s for you because, no matter who you are, it’s hard to know how to be happy in a world that is chaotic, contradictory, and unpredictable, and you have probably spent time wondering what might make you happier than you currently are. It’s for you because even if you’re a perfect Kinsey 0 of a man, you might also be a Betty.

I don’t believe in niche. The human experience is not niche.

This is a queer feminist play, and it is universal, and you are (whoever you are) welcome.

‘Collective Rage: A Play in Five Betties’ is on at Southwark Playhouse until 17 February (southwarkplayhouse.co.uk)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments