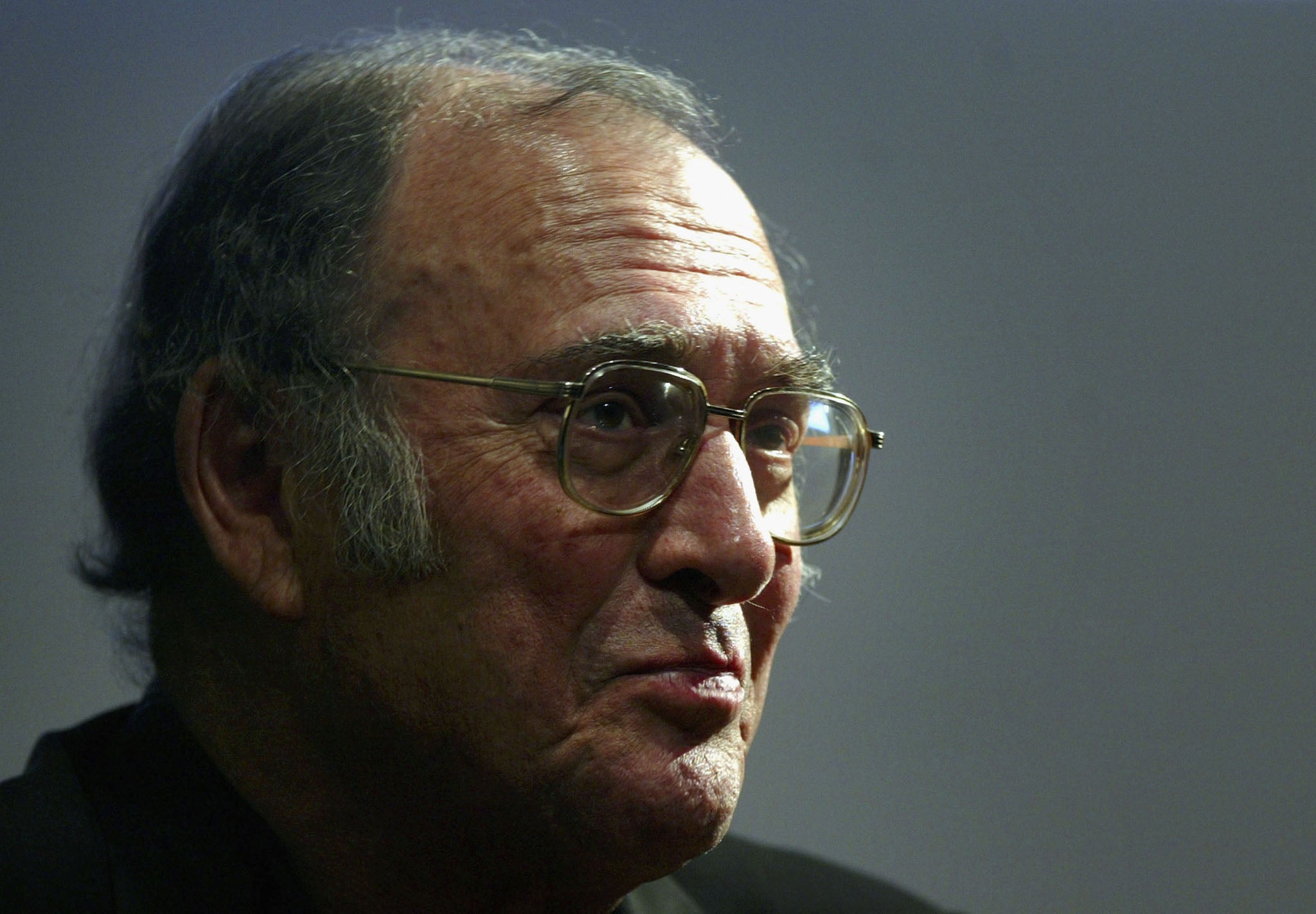

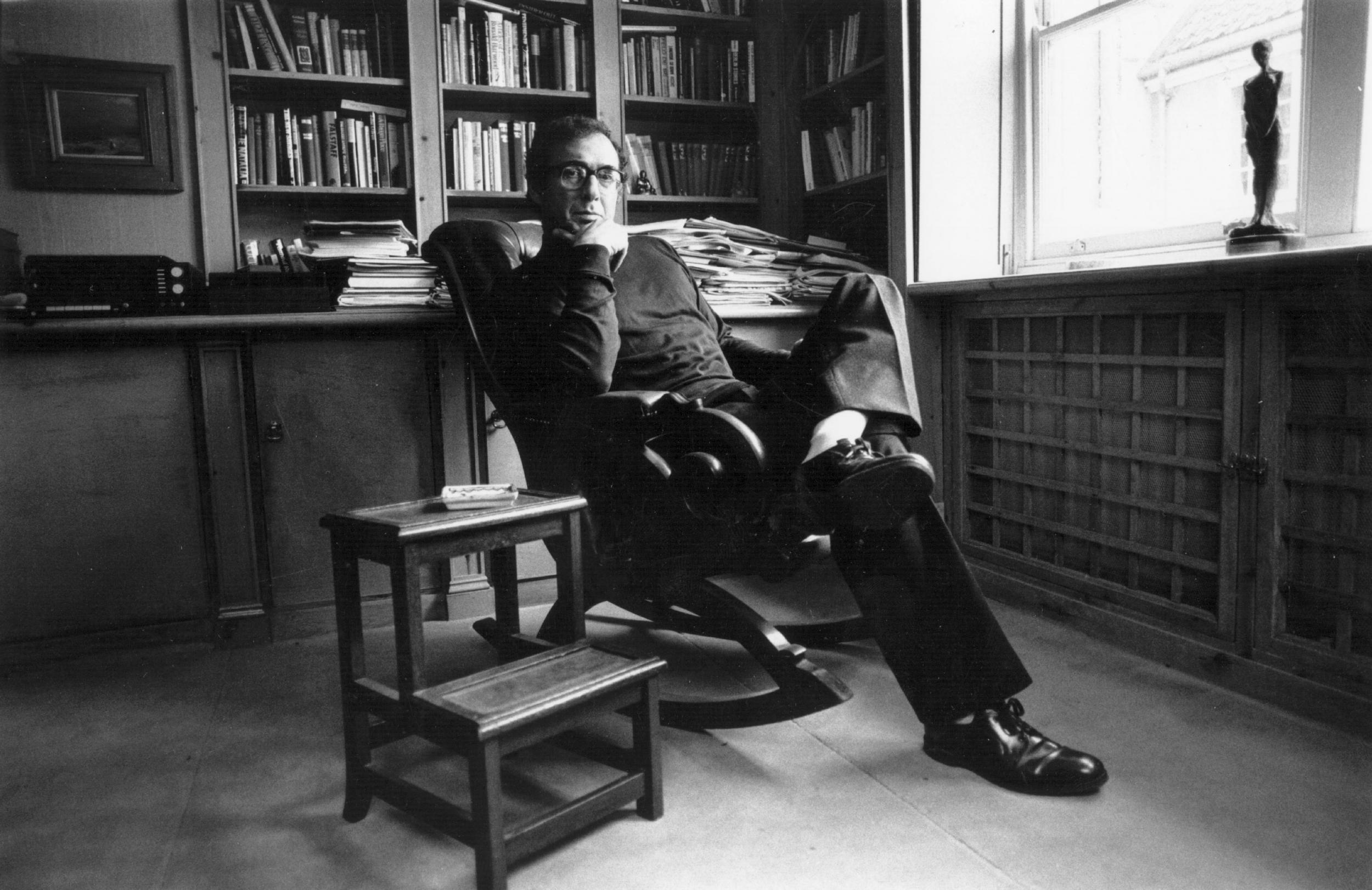

Harold Pinter was a harbinger of our age of threat

A new season of his one-act plays will show that time is proving the playwright right about democracy, fear and the super-rich, says Sarah Crompton

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Mountain Language by Harold Pinter was first staged in New York in 1989, in a double bill alongside his first play, The Birthday Party from 1958, the New York Times critic Frank Rich remarked that both were built to the same “grotesque conclusion” in which a defenceless man “is reduced to a quivering, speechless wreck by properly dressed thugs serving an unnamed organisation”.

“Mr Pinter,” he went on, “hasn’t changed that much in 30 years, but neither has the world around him. This is still a century in which terror can arrive with a stranger’s knock at the door. The silence that follows – the deadly silence of abject fear – is the ultimate Pinter pause.”

Another three decades later, and 10 years on from the playwright’s death, that sentence remains true. Pinter is still utterly relevant, a chronicler of his own uncertain age and a harbinger of one he did not live to see. His prescient sense of the threats lurking all around us is the reason his plays still seem so topical, whatever the decade in which they were written.

Jamie Lloyd’s new season of Pinter plays at the Harold Pinter theatre offers a chance to see all the playwright’s one-act plays. When it kicks off on 6 September, it will offer a unique opportunity to test their vitality and to assess their merit. In particular, it will put the overtly political plays of his later career under the microscope.

For not everything Pinter wrote was immediately acclaimed. The Birthday Party (not in the season) was a famous flop, closing after just eight performances. Reviews for Mountain Language – on the opening bill, alongside One for the Road, The New World Order and Ashes to Ashes – were not uniformly favourable when it opened at the National Theatre in 1988. In fact, as Michael Billington notes in his Pinter biography, they “ran the gamut from wholehearted admiration to lofty derision”.

What people most objected to about the 20-minute drama, which was inspired by a visit to Turkey and his experience of the Kurdish language, was that Pinter explicitly brought Britain into the equation. “From my point of view,” he told the critic Mel Gussow, “the play is about suppression of language and the loss of freedom of expression. I feel therefore it is as relevant in England is it is in Turkey.”

Writing about a revival in 2001, Charles Spencer in The Telegraph couldn’t contain his irritation. “It strikes me that Pinter is hitching an undignified ride on other people's all-too-real suffering, under all-too-real tyrannies, in order to excoriate a nation, Britain, that rightly allows him complete freedom to indulge his fantasies.”

Yet, while literal equivalence is still hard to see, particularly as the picture in Turkey darkens by the day, 30 years on, in an age of Trump, Brexit and European populism, Pinter’s concerns, his nagging sense that democracy is only skin deep and that liberal societies are endangered by the natural authoritarianism of the men who lead them, seem ever more important. “I think we should look at what’s happening in our own societies and at the wider idea of democracy. It’s used more and more as a fake word and a sham word and it doesn’t mean anything,” Pinter told Billington around the same time.

He cited Mountain Language – “brutal, short and ugly” – in the lecture he delivered via video on winning the Nobel Prize in 2005 when he was talking about the difficulty of writing political theatre, before he unleashed a torrent of almighty anger on the United States and its foreign policy decisions. Mark Rylance will read the lecture as part of the Pinter season, and even without Pinter’s own rich declamatory tones it still packs the most extraordinary punch.

In its opening sentence, it looks back to something he wrote in 1958. “There are no hard distinctions between what is real and what is unreal, nor between what is true and what is false. A thing is not necessarily either true or false; it can be both true and false.”

This seems to be the underlying mantra of Pinter the playwright. He deals in the murky areas of human behaviour, where motive and desires are muddled and ultimately unknowable. This is why studying him in school – as so many of us are forced to do – is so often unedifying. By analysing his characters and his plays to death, by seeking exact definitions of each word and each phrase, and of course each pause, you risk destroying the inherent drama that the ex-actor always provided in a theatre. Works such as A Kind of Alaska and Moonlight thrive in a sort of half-life where nothing is absolutely certain; their power lies in the things left unsaid or unexplained as much as those we understand.

But as a citizen, Pinter went on to say in his lecture, he had to ask what is true and what is false. His furious sense of moral right, of justice, made him call out the machinations of politicians, made him want to make explicit the dangers of oppression, suppression and the resort to war. That is why so many of his later plays were overtly political. He couldn’t remain silent.

That tension between the playwright’s pursuit of ambiguity and the man’s desire to speak out will be on evidence throughout the Lloyd season. It features many of Pinter’s comic pieces, queasy studies of odd relationships and eternal struggles between the powerful and the powerless such as The Collection, A Slight Ache and The Dumb Waiter. Later pieces such as Celebration and Party Time are satires on the super-rich – another theme that has come to seem more prescient as the years have passed. All are gifts for actors, innately theatrical, supremely dramatic; no wonder the season has attracted such a starry cast from Danny Dyer, Martin Freeman and Tamsin Greig, to Jane Horrocks and Lee Evans, coming out of retirement for the privilege of performing the great man’s words.

For an audience, Pinter’s chilly brilliance and his righteous anger can sometimes make him an easier playwright to admire than to love. But more than any other writer I can think of, there is a sense that time is proving Pinter right. His obsession with the fraught business of communication, his sense that memory is a malleable and uncatchable, and above all his warnings about the fragility of the very fabric of society make him look like a prophet as well as a poet. It will be fascinating to see where this season of his plays leaves his reputation.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments