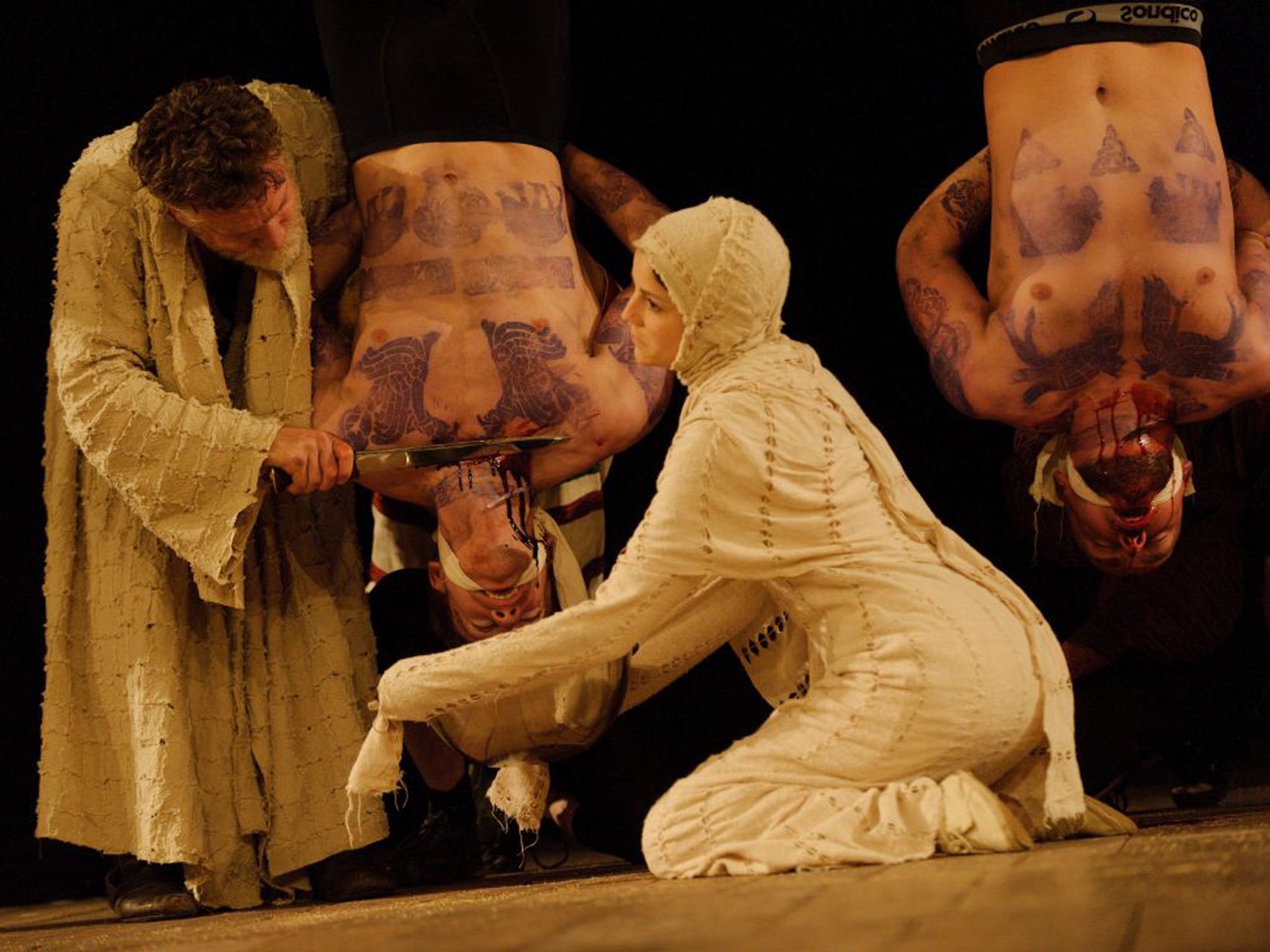

Guillaume Tell's gang-rape scene caused uproar at the Royal Opera House – but the portrayal of extreme sex and violence on stage is nothing new

Last year's "Titus Andronicus" at the Globe has spectators fainting in droves

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The mass booing that greeted the gang-rape scene at the first night of the Royal Opera’s production of Rossini’s Guillaume Tell this week might almost lead one to believe that extreme, and arguably gratuitous, sex and violence are unprecedented in our opera houses and theatres. How wrong that would be.

One doesn’t have to go very far to find other examples. Indeed, one doesn’t even have to leave Covent Garden. In the Royal Opera’s most recent production of Verdi’s Rigoletto the depravity and seediness of the Duke’s court is not just sung about, it is there, with simulated male oral and anal sex. And some female nudity in the interests of balance.

Or go back just three years to another round of Covent Garden booing when Dvorack’s opera Rusalka was set in a brothel, not the usual habitat of the story’s mermaid. And don’t think that taking an idiosyncratic approach to the story, followed by audience consternation is a recent phenomenon. And audiences at the Royal Opera House were nonplussed in 1994 by Richard Jones’s Wagner’s Ring, which had the Rhinemaidens in latex nude costumes.

Covent Garden audiences did show proper British priorities in becoming more alarmed by (and booing) last year’s production of Mozart’s Idomeneo, which seemed to feature cruelty to animals, with a dead shark on stage.

They must be piqued down the road at the London Coliseum, home of the English National Opera. It was that address that for three decades now has led the field on gratuitous sex and violence. Not for nothing was its 1984 production of Tchaikovsky’s Mazeppa with bodies hung on meat hooks known as “the chainsaw Mazeppa”. Indeed, the violence really was carried out with said implement.

After the millennium the ENO treated Verdi a little more respectfully, but only a little, with Calixto Bieito’s A Masked Ball seeing the 12 conspirators all seated on lavatories – followed later in the show by the rape and murder of a male youth.

Britain was spared the same director’s version of Mozart’s light opera Die Entführung aus dem Serail, which treated Berlin audiences to nipple-slicing, masturbation and singers urinating on each other. At least, the singers could claim that drinking before the performance was artistically necessary.

What could be more graphic? Step forward the creative team of Shakespeare’s Globe. Proving that theatre doesn’t like to be upstaged by opera, last year’s Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus had spectators fainting in droves (including a theatre critic of this paper). It is the most violent of Shakespeare’s plays. And one might assume that it was the scenes of a woman having her hands and tongue severed after being raped, or a pie being made with the ingredients of murdered characters that caused the fainting. Not so. Those scenes are in the script. Most of the fainting came at the unscripted scene of the murder of a servant woman by repeatedly thrusting a sword into her vagina.

And those who were quick to point out that the director of the Guillaume Tell gang-rape scene was a man (the Italian, Damiano Michieletto) should note that the director of Titus Andronicus was a woman, Britain’s Lucy Bailey.

Of course, directors will generally deny that their extreme scenes are gratuitous, they will say that they are suggested by the script or libretto. Indeed the head of the Royal Opera said this week that the Guillaume Tell gang-rape is an illustration of the reality of warfare, and the libretto also “suggests” a brutal domination of the Swiss women by the Austrian military.

One question all this does provoke is the implications for children in the audience. It remains extremely rare for children to be forbidden entry to an explicit stage performance, though in its current dance production about pornography We Want You to Watch, the National Theatre does advise that it is “suitable for ages 16 plus” and says it contains “adult themes”. The Globe never puts an age minimum on its plays but its brochure did warn that Titus Andronicus was “grotesquely violent” so you could argue that mum and dad might have had an inkling of what to expect. Interestingly, when the production was shown in cinemas and on DVD it was rated 15, the first Shakespeare’s Globe production to receive an age rating for screen transmission. Of course, unlike cinema, TV and DVD, theatre and opera in Britain have no regulator to demand cuts, give age ratings, or even register a criticism.

The Royal Opera House’s brochure contained no warnings about Guillaume Tell, and its website warned coyly: “The production features a scene involving an adult theme and brief nudity.” Following the outcry this week there is now a warning about “a scene depicting momentary nudity and violence of a threatening sexual nature”.

However, few parents will have booked to take the family to Guillaume Tell. For young viewers there is a horror far more traumatic than the brutal sex and violence. It is four and a half hours long.

Controversy cut

The Royal Opera House has climbed down over a controversial rape scene in its new production of Guillaume Tell, after it was met by boos on the opening night.

A scene in which a female character was sexually assaulted by soldiers and stripped naked was met with jeering and catcalling, at one stage drowning out the music.

Director Damiano Michieletto has subsequently tweaked the scene, the Opera House has announced, despite senior figures earlier stressing it would not be changed.

The scene has been edited so the woman, played by 28-year-old actress Jessica Chamberlain, is shielded by a tablecloth so she is no longer seen naked, while an incident in which a soldier molests her with a gun was cut.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments