From Light Shining in Buckinghamshire to The Skriker: is Caryl Churchill Britain's greatest living playwright?

We sift the evidence with those who know her

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Who is Britain’s greatest living playwright? Tom Stoppard has often been bestowed with this honour, as he was, again, in the barrage of press marking his comeback play The Hard Problem earlier this year. But, for many, there’s another clear candidate, Caryl Churchill – and her claim to the title is set to be showcased in the months ahead, with three major revivals of her work.

First, a production of Light Shining in Buckinghamshire, her early play about the English Civil War, opens next week at the National Theatre. Then in July comes Manchester International Festival’s take on her 1994 twisted fable The Skriker, starring Maxine Peake and with music by Antony Hegarty and Nico Muhly, followed by the transfer to the Young Vic of Michael Longhurst’s acclaimed production of cloning drama A Number.

But while her work fills stages yet again, we can expect the woman herself to remain elusive: she has long refused to give interviews. Lucky, then, that those who have worked with her are happier to discuss her work.

“Without doubt she is the most eminent playwright that we have at the moment,” says Max Stafford-Clark; his Joint Stock theatre company’s famous workshop methods helped give birth to Light Shining, as well as other works including Cloud 9 and Fen.

“She’s a major player and we don’t have many,” is the definitive view of David Lan, artistic director of the Young Vic, who collaborated with Churchill on 1986’s A Mouthful of Birds, a dance theatre piece inspired by Euripides’ The Bacchae.

What’s most remarkable about the 76-year-old’s long career is, perhaps, its restlessness: unlike most writers, she has never fallen into a groove of identifiable tactics or a predictable voice. Rather, her plays have continued to knock audiences sideways with their inventiveness – from deploying pioneering cross-gender, race and age casting in 1979’s Cloud 9 to using blank verse to satirise the greed of City stockbrokers in 1987’s Serious Money to highlighting the shrinking attention spans of the Noughties by creating 57 micro-plays in 2012’s Love and Information.

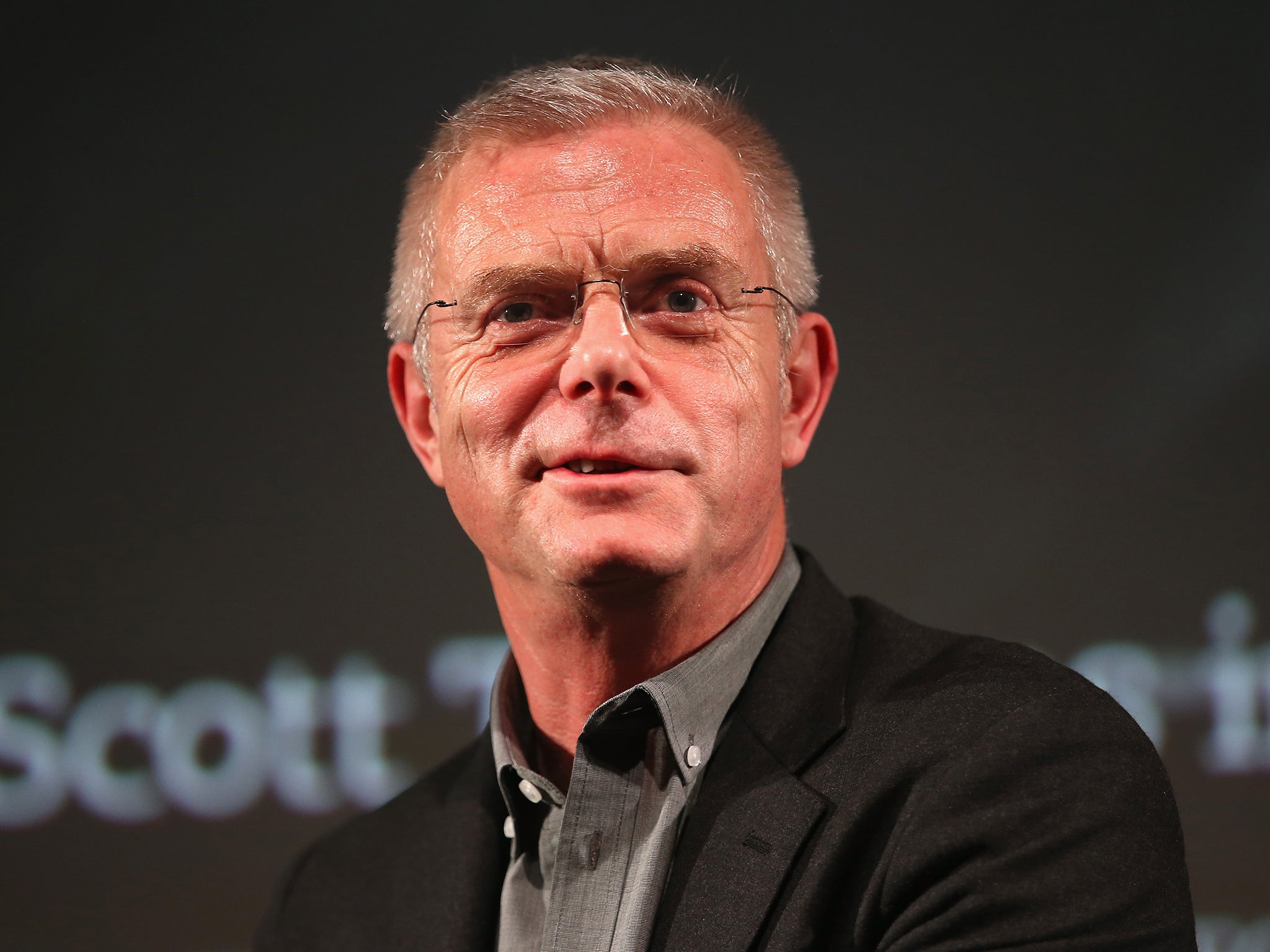

“Famously, it’s the form of the play she explores in almost every piece, but not in an academic way or for the sake of it,” says Stephen Daldry, who’s directed several Churchill premieres for the Royal Court. “The form will always fit the play.”

Daldry’s point is echoed by Lyndsey Turner, who is directing the National’s revival of Light Shining, a sort of historical verbatim play drawing on the 1647 Putney Debates, which saw the radical groups of the English Civil War debate with Cromwell about society’s future. “Her focus as a dramatist has never been an inward-looking one – her plays aren’t essays,” says Turner, “but living, breathing, red-blooded works.”

Manchester Royal Exchange’s Sarah Frankcom is directing The Skriker, a play certainly red in tooth and claw; Peake plays the title character, a shapeshifting spirit speaking in linguistically cartwheeling rhymes, who lures two teen mothers into a macabre, musical underworld. “When you’re in the hands of a playwright [who can] challenge your expectations of what theatre can be and do on a moment-by-moment basis, there’s nothing more thrilling,” Frankcom claims. “None of her plays could exist anywhere else but a theatre, and I don’t know you could say that about many other playwrights.”

The Skriker, with its musical overlay and supporting cast of strange, silent, dancing figures, was developed in 1994 with frequent collaborator, choreographer Ian Spink. It is rare that such an eminent writer is also so open to collaboration, but Spink chalks it up to a fidgety mind. “Generous and fearless in workshop and improvising stages, she was always open to some rather surreal ideas…,” he says, “[and] I think she has always been attracted by the way movement can convey so much ambiguty.”

Churchill often works closely with directors too; Daldry recalls her having a keen eye for everything from lighting to casting and adds that “she’s the most gorgeous woman in the world – the most fun you could have with anyone in the rehearsal room.”

Not that she does anyone’s job for them: her plays demand big staging decisions, and serious directorial nous. “She might apparently give you almost impossible things to achieve, but working with her you discover they are all achievable,” says Daldry, though Stafford-Clark is less sure about this last point.

“Certainly there were some plays that I couldn’t get a grip on,” he confesses, before adding modestly that when you are directing a modern classic like Top Girls – her 1982 hit that famously opens with a surreal dinner party of significant women from history – “you know that you’ve got your hands on a Rolls Royce. It makes even the most callow driver look good.”

Meanwhile, experiencing Churchill’s plays is rarely less demanding for her audience. If there is a thematic thread to her word, it’s her unflinching interest in the human capacity for violence, be that domestic (neglectful parents and abused children are a recurring theme) or geo-political, or both, such as in 1991’s Mad Forest and its examination of Ceausescu’s’ Romania or her short 2009 play Seven Jewish Children. Her most terrifying skill is to link societal ills to the individual human condition – however dark – in us all, suggests Lan, who has also been a close friend of Churchill’s since they met in 1972.

“She touches something very deep in people’s sense of who they are; a poetic truth which is also an emotional truth which is also a political truth.” Ah yes, the politics. Another feature of Churchill’s left-leaning work is that she has not mellowed with age. Quite the reverse: “She’s a liberal humanist – and she’s become more radical,” claims Stafford-Clark. “It’s extraordinary, the way she’s kept abreast of the times.” Consider Seven Jewish Children, written in response to Israel’s assault on the Gaza strip, which became one of the most controversial plays of recent times, with critics of it slamming it as an “anti-Israeli rant” and “wantonly inflammatory”.

By straddling so many concerns, politically, formally and otherwise, Churchill – unsurprisingly – has had an enormous impact on contemporary drama. And it reaches far beyond these shores, Daldry points out: “She’s been one of the major influences over the last 40 years, not just in this country but across the world.” Turner, too, acknowledges that her generation owes Churchill “an enormous debt: we see in her an artist who asks as many questions of form as she does about content, who realises that it ain’t just what you say, it’s the way that you say it.”

And then of course, there’s the impact she’s had in shattering gender stereotypes when it comes to playwriting: that’s to say, she’s produced expansive plays for big stages – sometimes explicitly “feminist”, sometimes not. More fundamentally, she’s simply proved it can be done: she’s a leading playwright, and she happens to be a woman. “Caryl is like this beacon,” says Frankcom. “Until relatively recently, playwriting has been pretty male – she’s always been the playwright that says that there’s another way.”

In this respect, she’s “beyond-words important…” says playwright April De Angelis. “Women are taking over British stages and she’s the precursor. I was talking to a visual artist the other day who said there are no great women painters. You can’t say that with playwriting: there’s Caryl Churchill.”

‘Light Shining in Buckinghamshire’ is at the National Theatre, 15 Apr-22 Jun; ‘The Skriker’ is at Manchester Royal Exchange, 1-18 July; ‘A Number’ is at the Young Vic, 4 July-8 Aug. Stafford-Clark’s ‘Crouch Touch Pause Engage’ tours till 20 June; Daldry’s ‘The Audience’ is at the Apollo Theatre, 21 Apr-25 July; De Angelis’ ‘After Electra’ is at the Tricycle, London, 7 Apr-2 May

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments