Outrage at performances for all-Black audiences ignores the whiteness of theatre

A special performance for Black audiences at Stratford East has been mischaracterised by those trying to shut down the real issues, writes Nicole Vassell

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

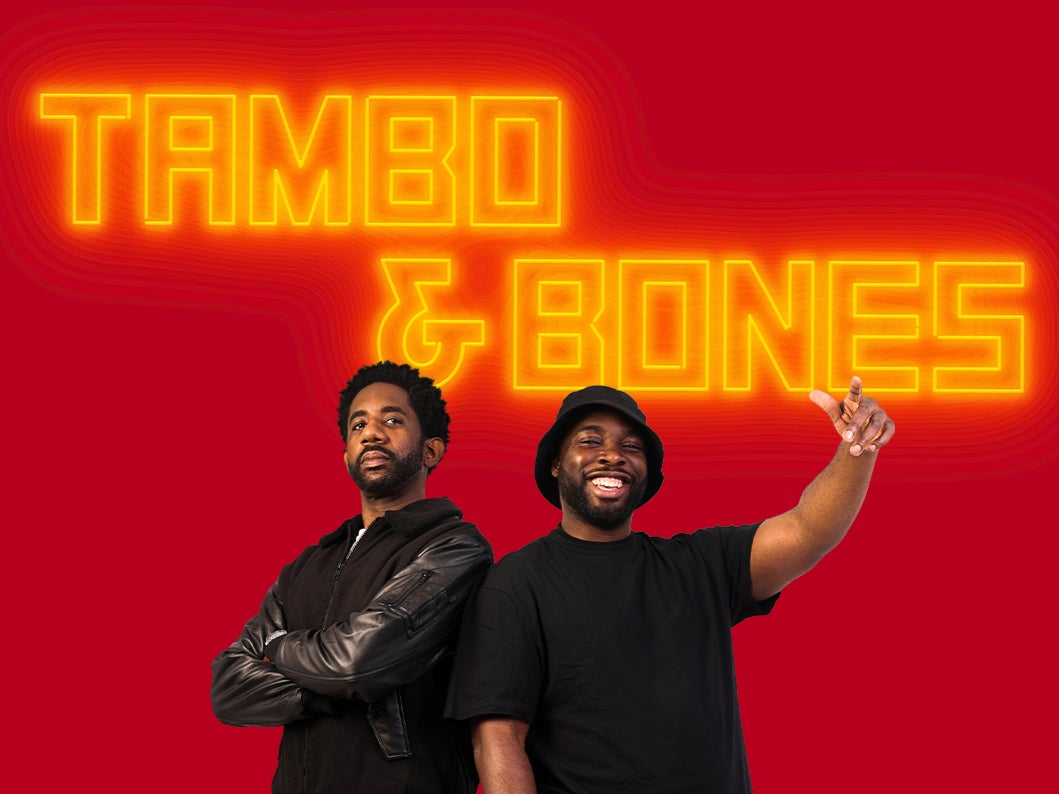

Your support makes all the difference.For a theatre programmer, it’s no small feat to have your production become the talk of the nation. Write-ups in major publications, hundreds of mentions on social media, and even a primetime discussion in front of millions on Good Morning Britain? A publicity dream! But for the team behind Tambo & Bones at Stratford East, the level of attention directed their way in the past week has likely been more of a nightmare.

From Friday 16 June, the east London theatre will host American playwright Dave Harris’s acclaimed satire about two Black performers who go from being stuck in a minstrel show to becoming rap superstars. With topics including the exploitation of Black culture and the historical complexities of performing for white audiences, it’s a play that intimately explores the nuances of race and racism. So, for one performance of the show’s month-long run, the theatre will host a “Black Out night”. While not restricting anyone from attending, the performance on 5 July is specifically organised to welcome Black audience members to “watch the play together as a community”, artistic director Nadia Fall explains.

Despite it being designed as a positive measure, it didn’t take long for a few bad faith reads to make this a topic of national interest. After an article reduced the singular performance as one in which white theatregoers were being urged to stay away, rather than highlighting the 28 other performances that welcome all who’d like to see the show, the ever-flickering flames of right-wing culture war outrage were fanned. Some involved in the show have had to publicly defend their actions with op-eds, as well as others locking their social media accounts to protect themselves from a barrage of racist abuse. As exhausting as this debate is, it isn’t entirely surprising. It’s a distraction tactic that hinders the very necessary discussion about discrimination in theatre.

The idea of a Black Out night is not unique to Tambo & Bones. In 2019, decorated young playwright Jeremy O Harris came up with the idea for his polarising three-act epic Slave Play, a show about race, sex and power dynamics in interracial relationships. For the 2022 London run of Harris’s next work, Daddy, the Black Out night returned, and has been a continued part of plays on both sides of the Atlantic ever since. “Over the last few years, a number of playwrights and directors in the US and the UK have created private and safe spaces for Black theatregoers to experience productions that explore complex, nuanced race-related issues,” Tambo & Bones director Matthew Xia explained on the Stratford East website. “I felt that with a play like Tambo & Bones, which unpicks the complexity of Black performance in relation to the white gaze, it was imperative that we created such a space.”

The growing popularity of Black Out nights speaks to the benefit some audiences get from the experience. Though there are continued moves forward for greater levels of diversity and a more inclusive atmosphere in theatre, it has been a white-centred medium for generations. For a show that directly tackles matters that are directly relevant to Black people, a specific moment for that intended audience to appreciate the work in a protected space makes sense. Marginalised people need to have environments to experience art together, free from the fear of potential microaggressions or ignorant misunderstandings. The concept would apply just as well to a play about male violence against women advertising for a women-only audience, or a play about transphobia only inviting trans people to attend.

But for some, this progressive initiative is flattened into a simplistic matter of unnecessary outrage and whataboutery. During Good Morning Britain’s debate about the topic, co-host Richard Madeley offered a take from a viewer who wondered what the response would be if a theatre would express the desire for only white people to attend. Of course, this hypothetical scenario ignores the fact of the general whiteness of theatre that already exists. A 2022 report by Arts Council England found that 93 per cent of audience members at theatres that receive their funding are white. There’s no need to imagine what an all-white theatre audience might look like; often, it’s already the case.

Yet, even having to dismantle this false equivalence feels like treading familiar ground. Whenever there are strategies that centre the experiences of a demographic that is not usually the focal point, there are cries of “wokeness gone mad” from those who very likely had no desire to take part at all. No longer is the conversation concerned with how Black people might feel more included or comfortable in a space that has long felt exclusive; the larger point is sidelined. It’s a distraction that does much more harm than good.

At the time of writing, Tambo & Bones’s Black Out night has sold out, more than a month ahead of time. In June, the Lyric theatre in Hammersmith will host a similar night for the UK premiere run of Jocelyn Bioh’s play School Girls; Or, The African Mean Girls Play. Black Out nights aren’t going anywhere anytime soon, but you can guarantee this won’t be the last time that a measure like this will have naysayers talking. Next time, instead of getting distracted by pointless debates, everyone’s energy would be much better used to understand why interventions like these are so needed in the first place.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments