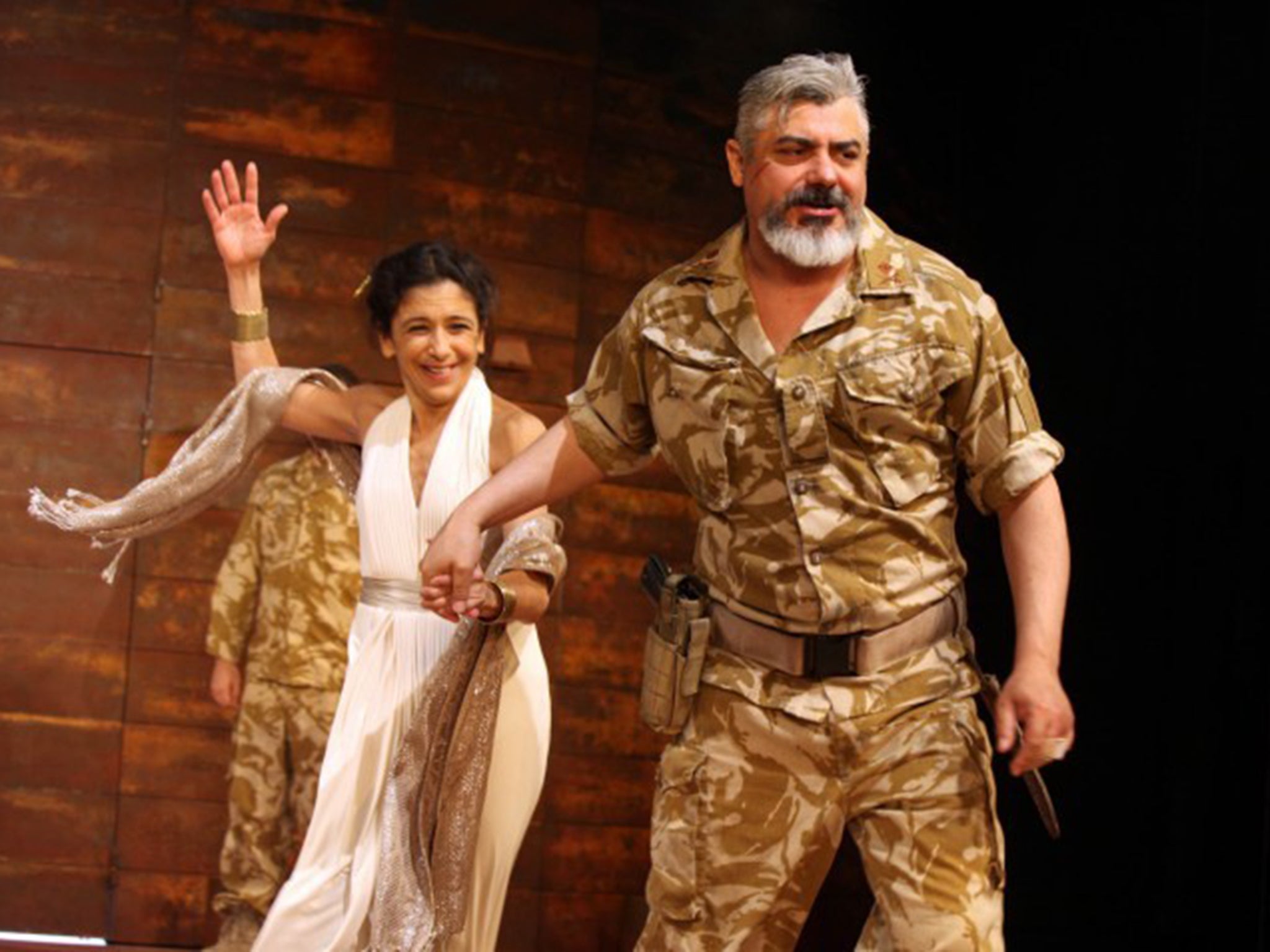

Antony and Cleopatra: Exulting in the intoxicating poetry of Shakespeare's most sensual love story

This is a sublime drama of immortal longings

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Despite its corpse-littered final act, Shakespeare critics have been reluctant to grant Antony and Cleopatra the same status as the “great” tragedies, Hamlet, King Lear, Othello and Macbeth. This may be because it’s “merely” a love-tragedy, like Romeo and Juliet – a melancholy folie à deux between infatuated couples, but scarcely a matter of earth-shaking importance. Some moral critics questioned the worth of a drama about a famous man deranged by lust. Others, puzzled by its occasionally jocular tone, suggested it was a “problem play”.

I never had a problem with it. From my seat at the Old Vic in the 1960s, it seemed a triumph of romantic subversion. I detected in it delicious notes of anarchy, as if Shakespeare had removed the leash from his imagination and played with his own dramatic tropes. He gives us Roman soldiers talking familiar cant about bravery and nobility, just as they do in Julius Caesar, only to mock them. He gives us a heroine who beguiles men but, instead of a dreamy Ophelia, an innocent Cordelia or a witty Rosalind, offers a fully rounded femme fatale.

The play deals with the orbits of Venus and Mars, and the action zips back and forth between them, as though between two states of mind. Here is Rome, where important men strut about, talking about dividing “the world” between them. Long passages involve breathless chronicles of bravery and derring-do. The word “honour” is bandied as the highest virtue.

There is, however, a counter-tendency: the word “fortune” keeps recurring, reminding the soldiers that battles may be won by Fate, not bravery. The chronicles of intrepidity often have a skewed, surreal quality: Caesar talks in awed tones about Antony’s remarkable palate during a famine: “On the Alps/ It is reported thou didst eat strange things/ Which some did die to look on.” As for the earth-dividing triumvirs – one is an ignorant drunkard called Lepidus, whom the others mock; and their negotiations of loyalty are enabled by the stratagem of having Antony marry Caesar’s sister. Very noble.

Shakespeare builds a picture of Rome as a place of dour, argumentative, bullying self-importance. Ranged against it are the “beds i’ the East”, where hedonism rules, nights are for carousing, and love and honest relationships are the greatest good. “Kingdoms are clay,” says Antony, kissing Cleopatra. “The nobleness of life/ Is to do thus.” You might mark him down as a romantic fool had Shakespeare imagined a lesser character as his lover. But Cleopatra is the Bard’s masterpiece of female characterisation: capricious, tempestuous, wrong-footing, sweet, furious, savage, melting, sexy (“Oh happy horse, to bear the weight of Antony...”) and fun to be with (“Let’s to billiards”). Though everyone compares her sighs and tears to storms and tempests, you feel that smaller-scale descriptions give you the real woman: “a wonderful piece of work”; “a lass unparalleled.”

She and her court represent a territory of excitement, a place of hot, seductive thrill, a region of human experience that’s wholly at odds with “noble” and “duty-bound” Rome – a surging Nile of passion that we’d love to visit, even if it might mean “We have kiss’d away/ kingdoms and empires.”

While the dramatic structure is no great shakes, and the plot’s simplicity rather effortfully sexed up by intercutting (no fewer than 15 scenes in Act 4!) it’s often remarked that no Shakespeare play offers such sublime poetry. It’s full of bittersweet regret, hopeless yearning, romantic intimations of a life out of the ordinary. Several phrases have become re-planted in literary history. Antony’s beautiful farewell to the good times in Alexandria – “Come,/ Let’s have one other gaudy night: call to me/ All my sad captains, fill our bowls once more;/ Let’s mock the midnight bell” – spawned three later titles: Gaudy Night, by Dorothy L Sayers; My Sad Captains, by Thom Gunn, and The Midnight Bell, by Patrick Hamilton. In Act V, with Antony dead, Cleopatra has all the best lines, as she starts to leave the world behind and embrace suicide: “I have nothing/ Of woman in me; now from head to foot/ I am marble-constant; now the fleeting moon/ No planet is of mine.” That heart-stopping enjambment recurs as she stands before Charmian and Iras for her final, transcendent robing: “Give me my robe; put on my crown. I have/ Immortal longings in me.”

No wonder she’s remained immortal for 400 years.

Shakespeare at a glance: Antony and Cleopatra

Plot

One third of the triumvirate of the Roman republic, Mark Antony, neglects his military duties to spend time in Alexandria, beguiled by Cleopatra. Summoned to Rome to fight pirates, Antony finds himself at odds with Octavius, whose chilly sister, Octavia, he is persuaded to marry. This plan to bind the triumvirs together backfires. After making a truce with the pirates, Antony returns to Egypt, where he crowns himself and Cleopatra rulers. War follows. Defeated by Octavius at sea (with Cleopatra fleeing with her navy in mid-battle), Antony wins a battle on dry land, then loses another – and blames Cleopatra. She locks herself away, pretending to have committed suicide. Antony tries to kills himself but is only wounded, and the lovers are briefly reunited. When Antony dies, Cleopatra welcomes death at the fangs of a snake.

Themes

Lust, infatuation and hedonism; loyalty and duty; the irresistible power of love.

Background

Written between 1603 and 1607, the play has more scenes than any other Shakespeare play. Famous pairings in the title roles include Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh; and Timothy Dalton and Lynn Redgrave.

Key characters

Antony, lovesick Roman triumvir.

Cleopatra, Queen of Egypt and femme fatale.

Octavius Caesar, one third of the triumvirate and future emperor of Rome.

Top lines

“Let Rome in Tiber melt, and the wide arch of the ranged empire fall: here is my space.” Antony defies Rome in Act 1 Scene 1.

“The barge she sat in, like a burnish’d throne/ Burned on the water; the poop was beaten gold…” Enobarbus describes Cleopatra’s first meeting with Antony, Act 2, Scene 2.

“Age cannot wither her, nor custom stale/ Her infinite variety.” Enobarbus continues to rhapsodise, Act 2, Scene 2.

“If I lose mine honour, I lose myself; better I were not yours than yours so branchless.” Antony explains his dilemma to his wife Octavia in Act 3 Scene 4.

“The odds is gone/ And there is nothing left remarkable/ Beneath the visiting moon.” Cleopatra mourns Antony, Act 4 Scene 15.

Echoes

Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor starred in Joseph L Mankiewicz’s four-hour film version (‘Cleopatra’, 1963). Samuel Barber made an opera out of it (1936). TS Eliot alluded to it in the second part of ‘The Waste Land’ (1922). Even the Carry On team celebrated it, in ‘Carry on Cleo’ (1964).

Luke Barber

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments