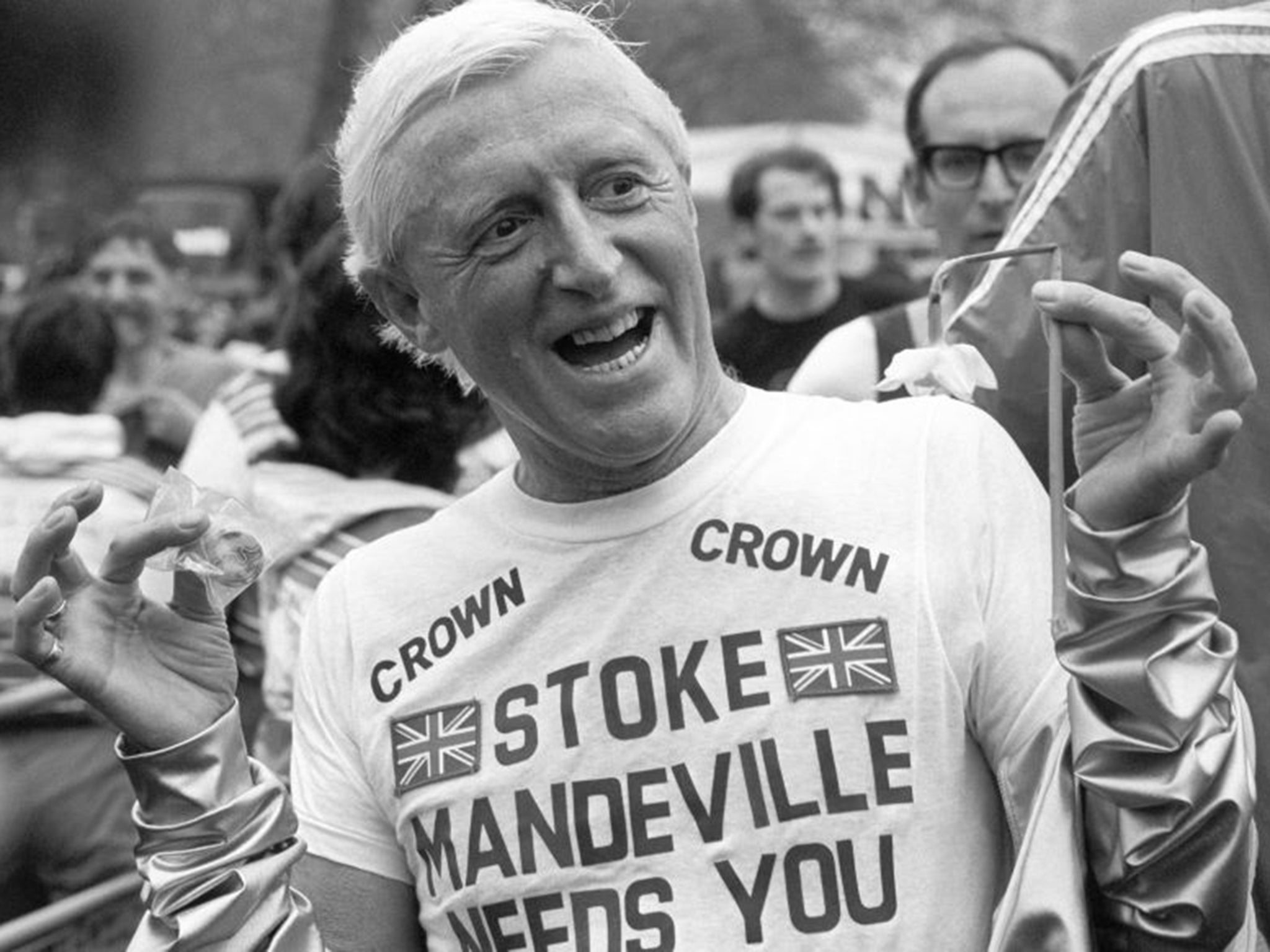

An Audience with Jimmy Savile: Why the notorious paedophile's story shouldn't be erased from history

Jonathan Maitland explains his decision to write a stage play about the crimes of the BBC DJ

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Soon after the Jimmy Savile scandal broke, a film editor at the BBC was given an unusual task. He was instructed to edit every trace of the presenter out of every edition of Top of the Pops he’d ever been in. The job apparently took several weeks.

The urge to erase Savile from history is understandable but should be resisted. Because until we have fully studied, understood and learnt from the mistakes of the past, we risk repeating them. That is why I’ve written a play about the scandal, An Audience with Jimmy Savile, which opens shortly at London’s Park Theatre. But why did I – a journalist – choose to tell the story using drama?

Like many, I followed the distressing saga closely from the start. Not least because I felt shocked and ashamed that my profession had failed to expose the unfeasibly high-profile criminal in our midst. In the course of 30 years reporting for Radio 4’s Today, BBC News and ITV1’s flagship current affairs show Tonight, I’ve exposed crooks, trolls and conmen at the highest level. But I had no idea what was going on. I therefore desperately wanted to cover the story – better late than never – and felt there was a huge public interest in doing so. There were many important issues: our attitudes to children; the way we deal with allegations of abuse; our cravenness before celebrity; the limitations of our libel laws. Most crucial of all: how on earth did he get away with it so brazenly for so long?

After a year of reflection, however, I realised that drama – or a dramatised form of journalism – was the most effective way of unlocking the essential truths of the story. The play depicts real events but some scenes are imagined. Its narrative has two strands. One, inspired by Savile’s two appearances on This is Your Life, centres on a congratulatory TV show dedicated to him at the height of his fame. The other follows Lucy, a composite character based on several of Savile’s victims, as she struggles to convince people of the abuse she suffered at his hands.

The techniques involved in play-writing differ from those of journalism. In drama, what is not said can be more important than what is said. The most vital and heart-breaking element of the scandal, for me, was that parents didn’t believe their children when they said they’d been abused by Savile. We know this from the many poignant victim testimonies laid out in the myriad reports. But it is very hard to convey how that denial happened in a factual TV programme. These episodes were private and people are understandably reluctant to talk in front of the camera. There is a moment in the play when Lucy tries to tell her father what she went through but he refuses even to engage with her. That, we hope, will be a lightbulb moment for the audience: it shows how the seeds of mass denial were sown.

There is still room for traditional reporting however. One key scene is a virtually verbatim staging of an inept police interview with Savile in 2009. The officers were investigating abuse allegations but no charges were brought, mainly because Savile manipulated his inquisitors to an astonishing degree. In a recent documentary that incident lost much of its significance because it used only a close-up of the transcript. But when we performed that scene at a public read-through of the play five months ago, the reaction was extraordinary. Afterwards, the audience said that was the moment when they realised how Savile got away with it. We knew then that drama could add something crucial.

The key decision I made was to devise the character of Lucy. After speaking to victims, we decided the most effective way of conveying their experiences was to coalesce them. The women we spoke to were gratifyingly supportive: after so many years of not being listened to or believed, they understood what we wanted to achieve and agreed this was an effective, legitimate way to do it. Then there was the casting. The inconvenient truth is that Savile was entertaining and charismatic. That, to quote a senior police officer, is how he “groomed the nation”. We needed someone who could cover those extremes. Alistair McGowan, a very fine stage actor as well as a skilled impressionist, fitted the bill perfectly.

There were other devils in the details. Chiefly, how to depict Savile’s crimes. Visual recreation was out of the question. There is, however, some distressing verbal detail in the play because, despite widespread coverage of the scandal, a surprising number of people still think Savile was not much more than a prolific sexual harasser when he was in fact a brutal, psychopathic paedophile and rapist.

Another challenge has been the public reaction to the project. Initially, some took to Twitter to accuse me – in graphic terms – of being, among other things, “a sick f***, profiteering from misery”. I didn’t agree, obviously, but understood their concerns. After engaging with every one of them and reassuring them that it was an honourably intentioned piece of work, the hostility abated. Indeed, most of those critics are now supporters. As for profit, if there is one, a substantial proportion will go to victims of abuse.

This acceptance was crucial. If a critical mass of survivors wanted the project to end, I would have aborted it. But the opposite has happened. Indeed Peter Saunders of the National Association for the Protection of People Abused in Childhood, with whom I have discussed the project in detail, says the play is “a serious part of the conversation we need to have about abuse”. Despite the subject matter, though, the story is, at its core, an optimistic one. Ultimately it is about bravery, forgiveness and the ability of a fractured family to heal.

I understand the desire to sweep things under the carpet. That’s what kept that BBC film editor busy for so long. But that is also what enabled Savile to do what he did. Sticking fingers in our ears and covering our eyes is no longer an option.

‘An Audience with Jimmy Savile’ is at the Park Theatre, London N4, from 10 June to 11 July (parktheatre.co.uk)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments