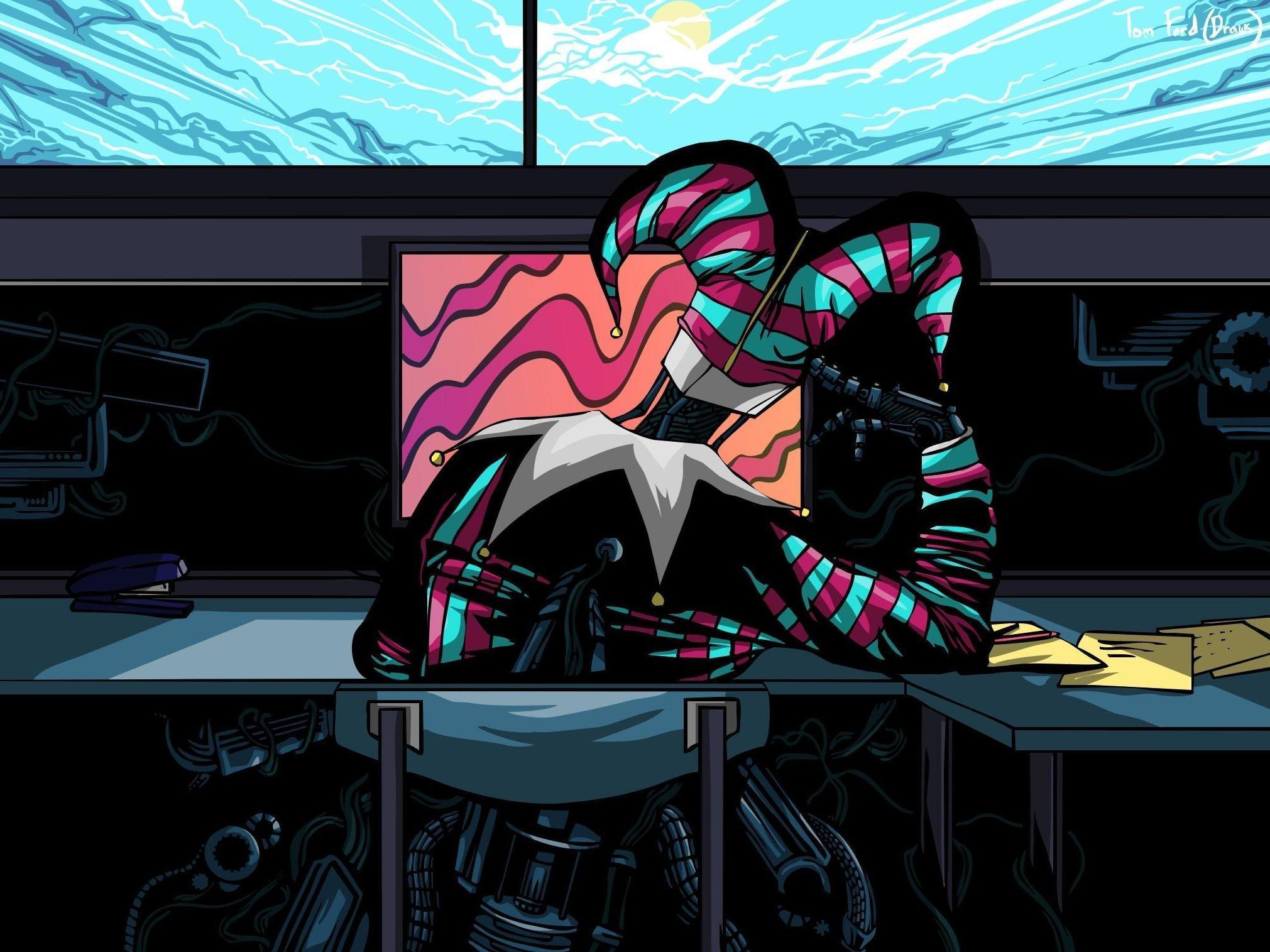

How standup comedy compares to an office job

Continuing his series, standup comedian Dan Antopolski ponders the difference between the glamorous life of comedy and a ‘proper’ job

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Everybody has a past and I wasn’t always a comedian. I used to be a baby – and I was a damn good one, crawling over here, crawling over there, somewhat focussed on breasts and given to yammering incomprehensibly to a roomful of adults – strange to imagine now. But as soon as I had mastered babyhood I cast it aside. This is the way with serial entrepreneurs like me and Elon Musk: we bore easily and must move forward like a shark. So I tried childhood for a bit and then made a few reluctant experiments with the job market. In my mid-twenties I wound up in comedy and never looked back.

“Find a job you love, and you will never have to work a day in your life.” Paraphrases of this sentiment can be found in the writings of Mark Twain, Confucius, Steve Jobs and Khalil Gibran – there is likely something in it. As soon as I started doing standup I loved it so much that I did indeed feel I had escaped the working condition. I performed first in London and then far beyond. I couldn’t believe I was being paid to do this, let alone paid well.

Several years in and two-thirds through a necessary can of Red Bull purchased from motorway services at three in the morning, I had worked out that once you pro-rate the driving hours, standup is not that glamorous. And when you’ve also deconstructed the magic of the stage that so bewitched you as novice and amateur, the whole occupation skews a bit menial. All comedians must pass through this gate; if we forge onward it is because we know other jobs are worse. This is why it helps to have done other things first: it can bolster your resolve, after driving six hours to die on your arse in a draughty function room, to have at least made acquaintance with the awful world of the proper job.

I had a number of crap jobs in my youth and they were certainly enough to motivate me in the opposite direction. I couldn’t hold them for long anyway, my attitude was too brattish: I had GCSE’s and was so much better than these jobs that I could not even do them well – I see waiters with this mindset now and one day I will punch one.

The experience that made me fear death by boredom over death by shame was in my late teens, in a Wernham Hogg-style office in a business park, via a temp agency. I know that many good people work in offices and I mean them no disrespect but I hated it. I worked in a cubicled area with two other temps. One of them, Joel, had such a generic face that when I wasn’t looking directly at him I could not recall it. I used to challenge myself by taking a good look at him and then walking to the water dispenser at the end of the aisle. Halfway there and his face would have gone. It was a Schrödinger face – it existed in no definitive state unless it was directly perceived.

To avoid the filing, I made a lot of these trips to get a cup of water and these trips begat bonus trips to the loo – my skin was never so vibrant. One day I made a wreath out of paperclips and wore it on my head, an ironic corporate version of an ironic flower-power version of a lowly clerk’s celluloid visor from the twenties. It was pretty political. The boss came past and asked me to remove it. I assured her that it would not interfere with my work. We each reiterated our positions and then she left, beguiled by my conviction.

That very evening, on my way home, I glimpsed between some buildings a half-constructed office block that would lose all charm when completed but which at that startling moment was a concrete Mondrian covered in ladders, a naked piece of fresh industry caught in the variegated pinks of sunset. It was very beautiful and I stopped my bike and stared at it. I can still picture it quite well, or the feeling anyway. It was incredible.

When I got home I received a phone call: it was the tinkling voice of my point person at the temp agency asking me to tell her about the paperclips and letting me know that the boss had invited her to invite me not to come in any more. I took it well. I wouldn’t miss the filing but I was concerned for Joel, who in the absence of my perception had no face and would find the work difficult.

Would I have sacrificed that industrial sunset to avoid all the filing? Yes, in a heartbeat. Standup can be tiring and embarrassing but it isn’t dehumanising and it won’t get eaten by automation. And even if robots do replace the jester, I can always fall back on my infant skill set, that worked so winsomely for me in the seventies. Meanwhile, if you see a man without a face let me know and I’ll come and perceive him, for it is Joel.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments