Should we steer clear of undisturbed snow?

Obsessed with perfect paths and tucked-away tracks, Will Gore recalls sledging on a disused railway embankment, in the second in a new series of reflections

It isn’t quite right to say there are no hills in Cambridgeshire.

True, to the north of the county there is plenty of flat fen. But to the south of Cambridge itself, the landscape undulates gently – the Gog Magog Hills, which lie just outside the city, aren’t as gigantic as they sound.

For children, inclines can be discouraging, the cause of bitter complaints. A fall of snow can change all that; then, slopes become highly desirable, necessary even.

In my childhood village of Linton, situated in Cambridgeshire’s most southeasterly corner, it didn’t snow often, especially in the mid to late Eighties. Those should have been my peak sledging years.

On the rare occasions that a few flakes actually settled, half the village seemed to make a dash for any available rise. Rivey Hill, topped with its striking, 1930s water tower, was for the bigger kids. For me, there was the old railway.

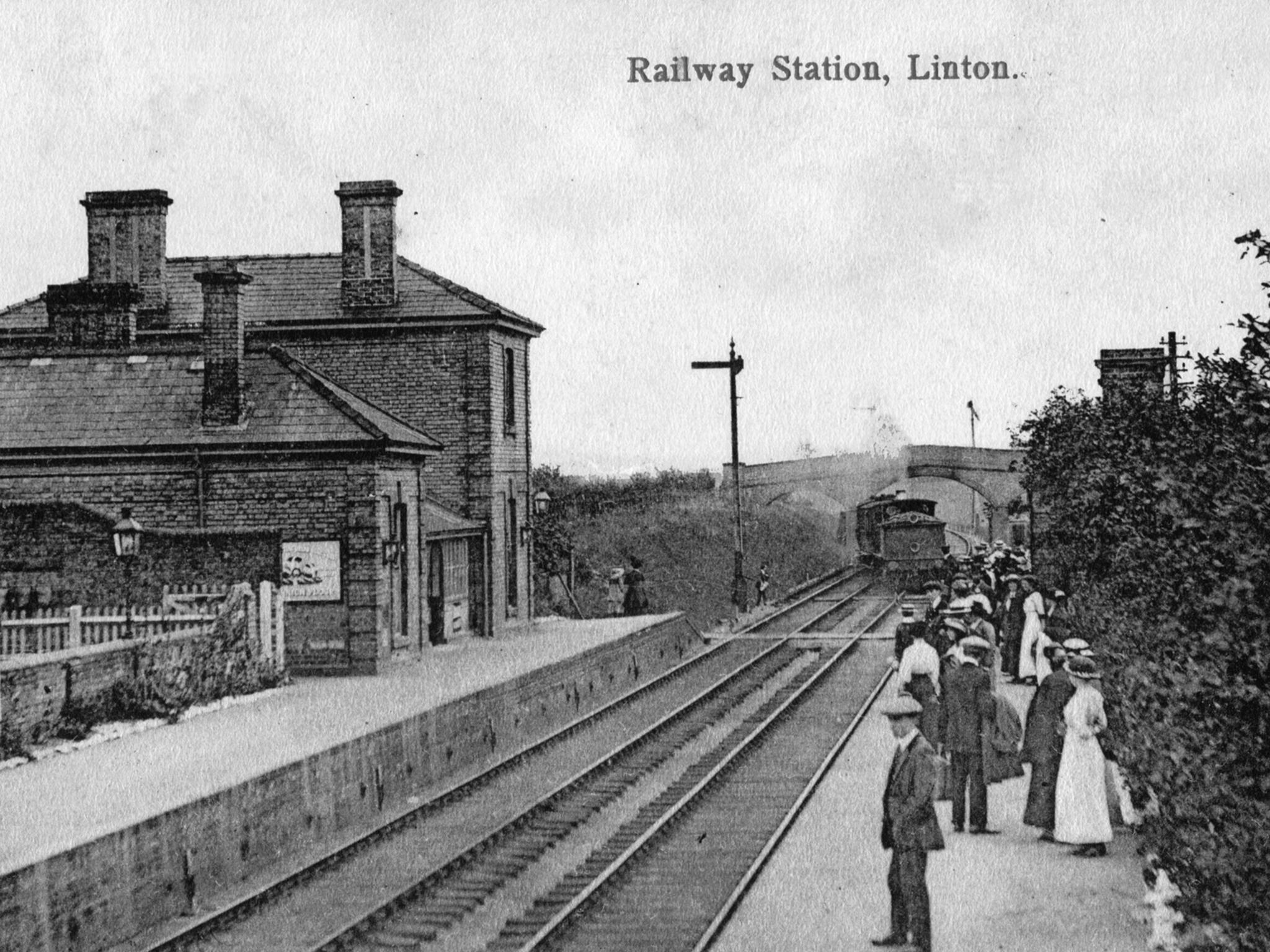

The line – part of the Stour Valley Railway – had once linked Cambridge to Sudbury in Suffolk, with various branch lines along the way. The section running through Linton was a victim of the Beeching cuts, closing in 1967, despite protests. The track had gone, but embankments remained, serving little purpose but to catch modest snow drifts among stiff, tufty grass.

Oddly, I never thought to investigate the building, which must have held its own mysteries

To reach the old line, we had to tug our toboggans across the main road, then veer past the police station and the houses in which the officers and their families lived (all long gone too now). Finally, we would trudge along a narrow path, hemmed in on the left by brambles and ancient hedges; on the right by disused outbuildings and greenhouses.

Eventually, the path emerged into the open at the top of an embankment, the once bustling little station a hundred yards or so away, beyond the cutting. Oddly, I never thought to investigate the building, which must have held its own mysteries.

Focused instead on the sled run before me I would aim for a route that was as free of tussocks and molehills as possible. There was always a temptation to head for the least trampled snow – but everyone knew that the pre-tobogganed parts of the slope would be faster.

My sledge was pillar-box red, and made of heavy plastic; better than traditional types with metal runners, but not a patch on the really lightweight ones that many of my fellow daredevils deployed. When the snow was thin on the ground, it was not always possible to be confident of reaching the bottom of the embankment, so pathetically slow was the going. Still, we would keep at it for hours, till gloves were soaked and faces were nearly frozen.

Sometimes, in summer, we would walk past the embankment, onwards through open fields on an easy hike that led to a pub in the next village. Once, I crept up on a rabbit, amazed that it was letting me get so close; only to stare into eyes that were puffy with myxomatosis. I don’t think I ever sledged the railway embankment after that – not because of the bunny, but because I graduated to bigger hills.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments