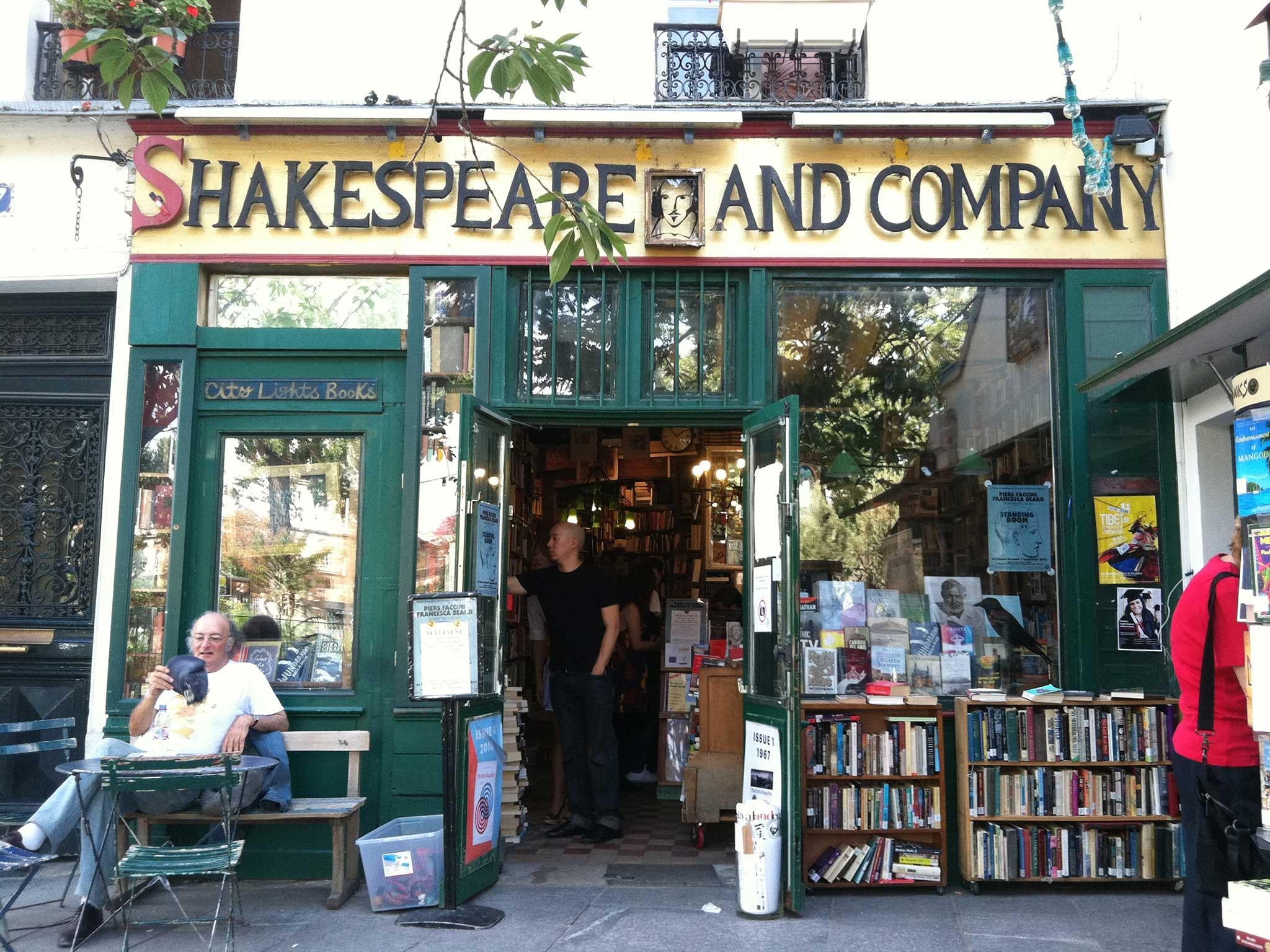

Shakespeare and Company, Paris’s famous bookstore where wandering writers are welcome

The tiny bookstore store on Paris’s Left Bank has hosted some of literature’s most revered figures

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Shakespeare and Company, the small, crumbling bookshop on Paris's Left Bank, may be the most famous bookstore in the world.

It was the first place to publish the entirety of James Joyce’s Ulysses when no one else would, and for decades it has been an informal living room – and sometimes a bedroom – for many of the most revered figures in contemporary literature: Ernest Hemingway and F Scott Fitzgerald, Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg, Lawrence Durrell and Anaïs Nin.

This week, the staff of the multicoloured storefront at 37 rue de la Bûcherie released a comprehensive history of the shop that originally opened at another location in 1919. The book was years in the making, nearly 400 pages of text, testimonies, and photographs from the store’s sprawling archive, crammed in mismatched boxes in a closet three floors up an uneven staircase. Conceived as a “memoir” instead of a history, the project is essentially a rigorous attempt to explain what, exactly, Shakespeare and Company is.

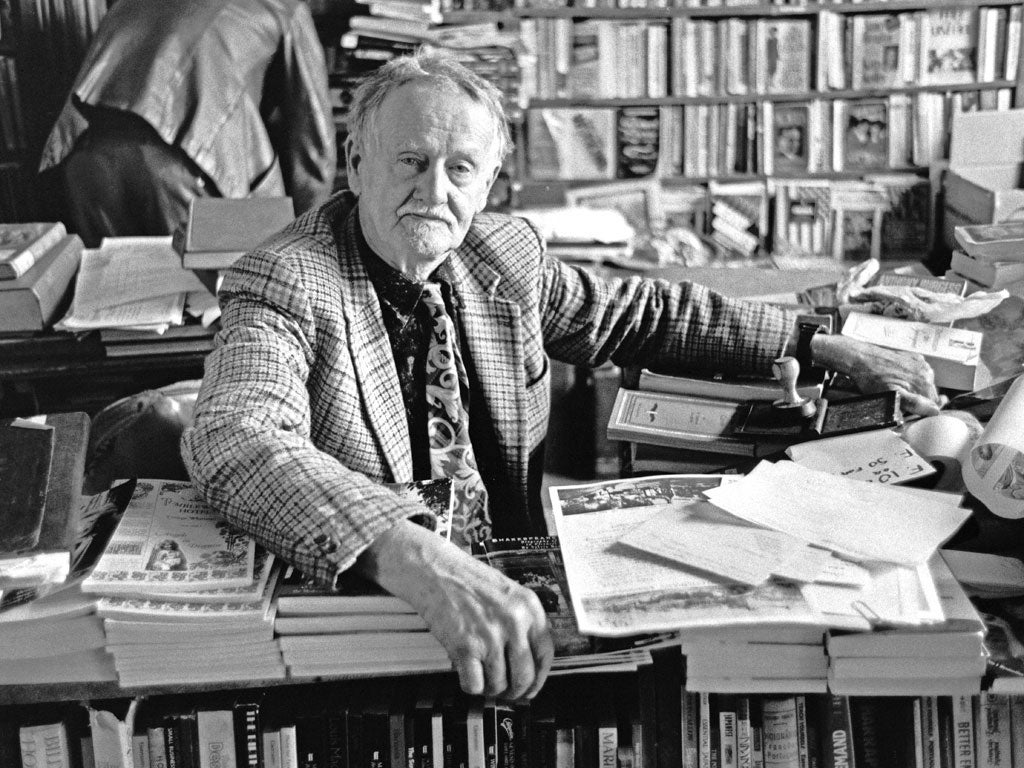

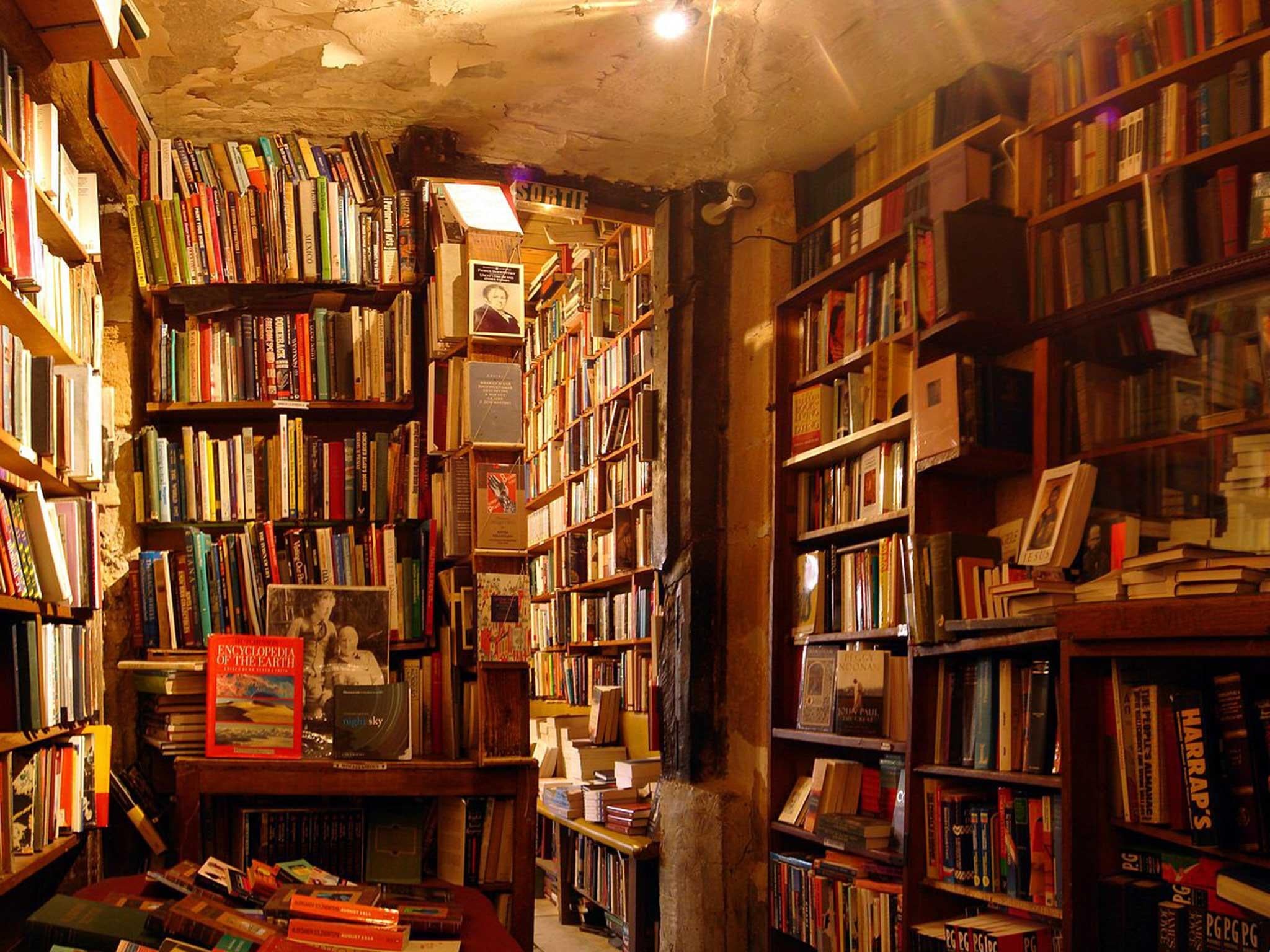

For George Whitman – the shop's American-born proprietor, who lived in the small apartment upstairs until his death in 2011 at 98 – Shakespeare and Company was many things. At his pithiest, he called it “a socialist utopia masquerading as a bookstore”, a bohemian rhapsody where visitors slept upstairs and red wine was served in empty tuna cans. But George – as he was known to so many – also considered the shop a living work of art. “I created this bookstore like a man would write a novel, building each room like a chapter,” he said. “I like people to open the door the way they open a book, a book that leads into a magic world in their imaginations.”

Whitman was not its founder: That distinction belongs to Sylvia Beach, who opened the original Shakespeare and Company on the nearby Rue de l'Odéon, which was forced to close in 1941 during the Nazi occupation of Paris, when Beach, along with thousands of others, was interned. In the late 1950s, she bequeathed the title of Shakespeare and Company to George, who named his only child after his predecessor. Sylvia Beach Whitman, 35, now runs Shakespeare and Company with her partner David Delannet, a Parisian philosophy student who wandered into the shop one day while she was sorting books inside.

“I think David quickly realised that if we were going to be together,” Sylvia said recently, “that the shop had to be part of his world as well.”

George arrived in the city after the Second World War to study at the Sorbonne on the GI Bill, and never left. He had acquired so many books that eventually he decided to open a shop of his own. In a diary entry from the spring of 1950, he wrote: “I hope to finally to have a niche where I can safely look upon the world's horror and beauty.”

Shakespeare and Company became that niche, where he hosted readings, impromptu dinner parties and, in later years, posed with visiting dignitaries in his pajamas or in a paisley blazer that he rarely, if ever, sent to the dry cleaners.

The shop would become a refuge for generations of wandering writers who turned up unannounced to live there. George called these travellers the “Tumbleweeds”, and the deal was that for two hours’ work every day – as well as the vague promise of reading one book every day – he would let them stay free in the shop, sleeping on cots tucked away between the stacks and showering in the public baths nearby.

“Be not inhospitable to strangers,” reads a sign that still stands like a motto in the shop today, “lest they be angels in disguise.”

The only other requirement for the Tumbleweeds – on George’s orders, and now Sylvia’s – is to write a one-page autobiography, often typed on one of the store’s typewriters, using sheets of pale blue paper. Shakespeare and Company now has thousands of these testimonies, some even from the children of previous Tumbleweeds.

“A lot of the Tumbleweeds are of a particular age,” Sylvia said recently, leafing through a book of these autobiographies. “It’s that age in life where you are looking to find your path. And there’s really no better place to ask yourself these questions than in the centre of Paris, being surrounded by stories.” Figuratively, of course, but also literally: piles of books can serve as chairs, and sometimes pillows.

For Jessica Thompson, 20, a Tumbleweed from New Zealand, the shop’s bizarre blend of fiction and reality has provided an invaluable stimulus for her own writing. “You’re forced to get words on the page,” she said. “You’re forced. Even if you produce s***, at least it comes out.”

Anneli Knight, 18, is another Tumbleweed. Born and raised on a farm in Buckinghamshire she says she has no immediate plans for the future and intends to stay in the shop “until they throw me out, really”. She, too, is working on a piece of fiction, tentatively titled Recollections of Her, about a man in therapy coming to terms with the suicide of the woman he loved. “That's part of the magic of the place,” Sylvia says. “Everyone has a tale to tell.”

The new book about the store takes the title of Whitman’s unfinished memoir, The Rag & Bone Shop of the Heart, a line from the WB Yeats poem “The Circus Animals’ Desertion”. It relies on hundreds of Tumbleweed testimonies from decades past, young people whose “ladders”, to cite the same poem, began in the store and ended in literary publication, university teaching positions or family lives in quiet suburbs. Leafing through the book, which will be available in US stores next week, it becomes clear that launching those journeys was always the point.

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments