Playing to their own beat: The photographer who captured the north’s juvenile jazz bands

Inspired by their imagination, photographer Tish Murtha found brilliance in the ubiquitous children’s toy bands found across working-class mining towns, writes Emily Goddard

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Mention Fats Waller or Louis Armstrong to any member of a juvenile jazz band,” wrote the late social photographer Tish Murtha, “and the reaction you are likely to get is one of blank ignorance.” Children’s marching troupes humming the National Anthem through a kazoo were as much a feature of working-class mining towns in the seventies as high-rise flats and dole offices, and they are often remembered today in rosy retrospection. But Murtha felt little fondness for them.

The photographer travelled with the juvenile jazz bands to capture their performances at parades and carnivals in the west end of Newcastle at a time of deep economic and social deprivation. Murtha discovered what she believed to be a militaristic charade that crushed the children’s spirits. “To be accepted into, and remain in the juvenile ‘jazz’ band a child must put aside all ‘normal’ behaviour, and become the plaything of the failed soldier, the ex-armed forces members, and their ilk; any spark of individuality is crushed by the military training imposed, until the child’s actions resemble those of a mechanical tin soldier, acting out the confused fantasies of an older generation,” she wrote in a scathing 1979 essay to accompany her photographs.

Murtha hated that there was no jazz music, and that the ensembles had political associations with right-wing movements. She added: “A Sunday Mirror article (summer 1977) reports an incident in which a juvenile ‘jazz’ band, booked by the National Front to lead one of its marches through the London area, was ordered to remove two of its young coloured members, before being allowed to continue the march; the band in question complied, with total disregard to either its full implications or the personal feelings of the kids involved.” She was also furious when the local authority in Newcastle allocated grants that included funds from taxpayers’ pockets to the bands at the expense of creative recreational activities that all children could enjoy.

Far more appealing to Murtha were the “toy bands” formed by jazz band rejects, which, she said, involved the child’s imagination almost as much as the official band denied it. These improvised troupes came together to fashion their own instruments from household items – pans became drums and the lids cymbals, while a broom handle made an ideal major’s mace. The charm of the toy bands was made all the more by their enthusiasm to practise fiercely. Murtha’s images of them capture the individuality of the children instead of the forced conformity of the juvenile jazz bands culture. “As was so typical of my mam, it was the underdog she wanted to champion,” says Ella Murtha, the photographer’s daughter.

The result of her time following the bands was a series of beautifully frank images illustrating the stark contrast between those children who were selected to join the big bands and those who took it upon themselves to make their own, far more creative, unofficial bands. “The anarchy depicted provided a fitting backdrop to the massive changes – neighbourhoods were being demolished – Newcastle was undergoing at the time,” Ella says.

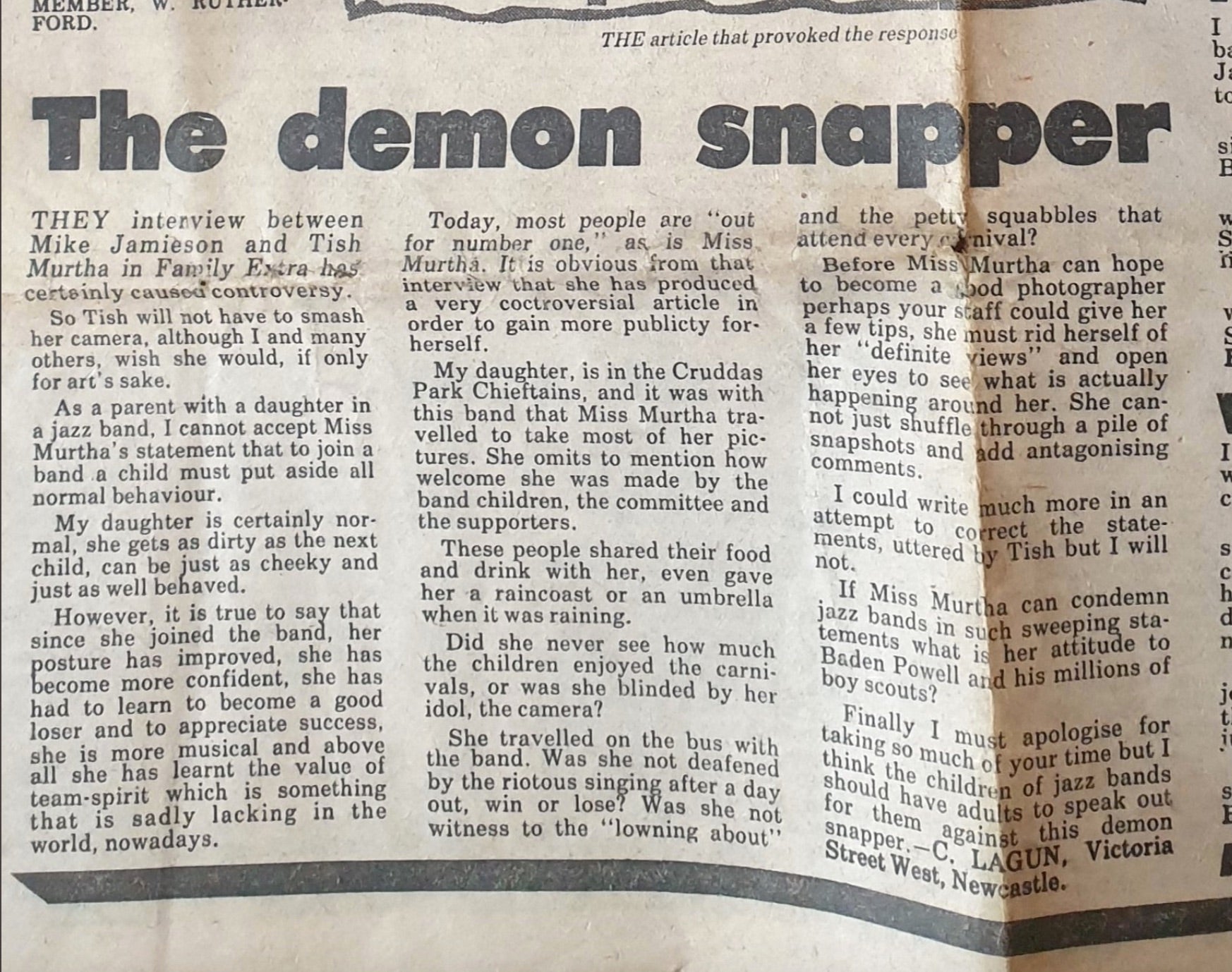

However, not everyone saw the splendour in her honesty. The series earned her quite a reputation locally and her very public criticism of the jazz bands earned her the nickname “The Demon Snapper”. Reams of column inches in local papers were dedicated to a backlash as angry readers protested. Responding to the controversy at the time, Murtha said: “Having observed the growth of these bands throughout my childhood, I feel I’m entitled as the next person to draw my own conclusions based on these experiences, and I find the photographic medium a suitable vehicle for their expression.”

The series was made while Murtha, who suffered a sudden fatal brain aneurysm the day before her 57th birthday in 2013, was employed through a youth opportunity programme at the Side Gallery in Newcastle. It became her first exhibition and was shown at the venue in 1979 before touring. Now the seminal work is being brought together in a new limited edition book, Juvenile Jazz Bands, that will be the final instalment of a posthumous trilogy of her work after Youth Unemployment and Elswick Kids.

A Kickstarter campaign supporting the launch of the hardback can be found here

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments