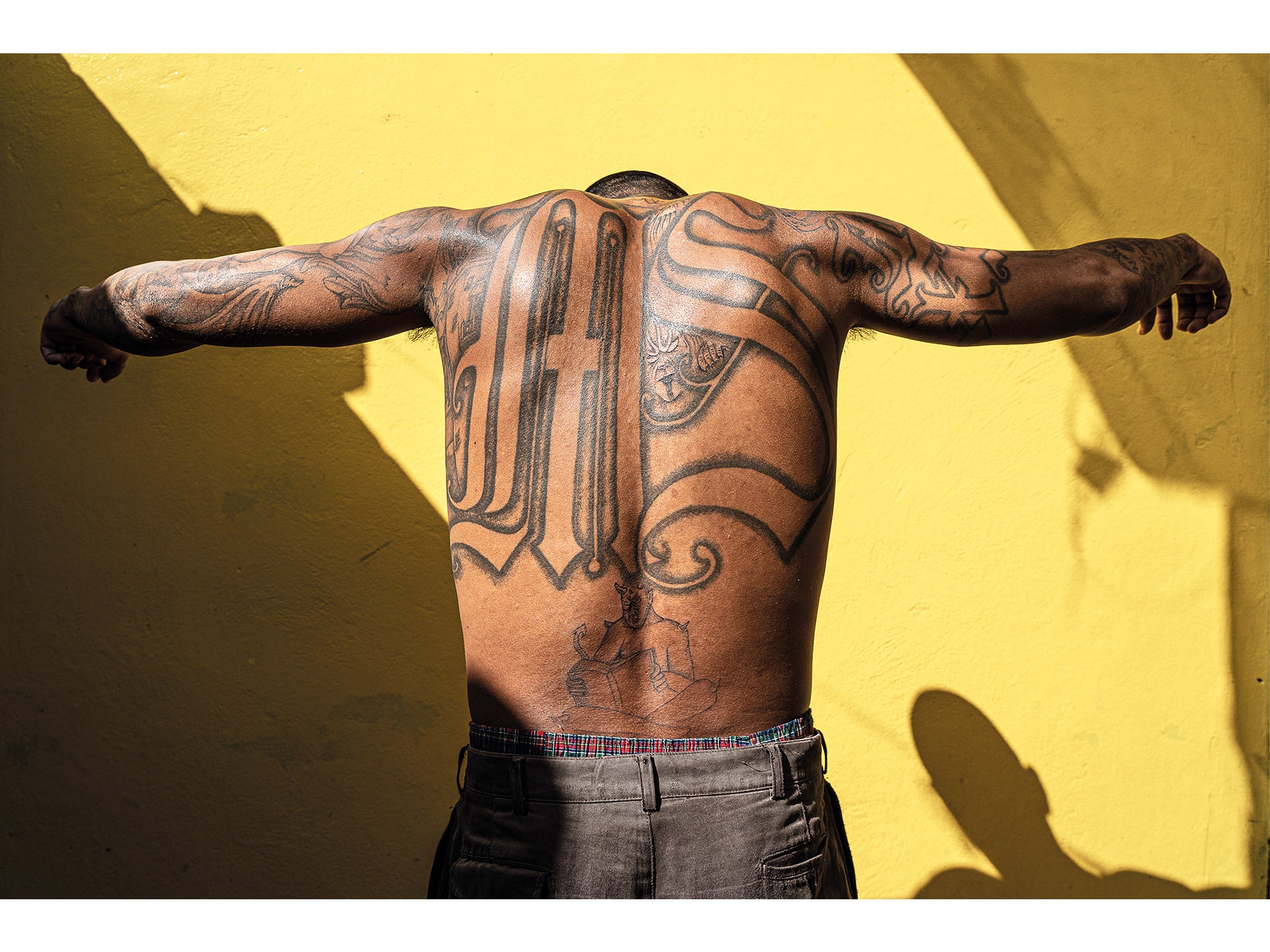

No way out: A look inside El Salvador’s brutal gang culture

El Salvador consistently ranks as having some of the worst murder rates in the world, largely thanks to a ruthless network of street gangs. Photographer Tariq Zaidi spent years photographing the impact gang violence has on the country

There is no room for ambiguity in El Salvador’s Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) street gang; under the motto “Kill, Rape, Control,” they’ve wrested control of much of the country along with its rival gang, Barrio 18. These street gangs are behind El Salvador’s shocking murder rate – 52 people in every 100,000 were murdered in 2018, the last year UN data is available. Killings aside, the gangs also dictate which neighbourhoods people can enter, and wreak economic havoc – MS-13 alone extort around 70 per cent of Salvadorian businesses.

London-based photographer Tariq Zaidi decided to photograph the country’s gangs following the news of migrant caravans moving towards the United States in 2017 and 2018. Some migrants were Salvadorians, escaping the violence in their home country. “When then-President Trump was calling central American migrant caravans ‘criminals’ and the like, I wanted to explore what kind of life these people were leaving behind,” he says. “I wanted to show the world just how dystopian El Salvador has become, and how the extent, scale and savagery of violence is unlike anything most of us have ever known.”

El Salvador’s gang culture emerged out of a long cycle of violence and dispossession. Although the Salvadorian migrants were spurned by Trump, the gang violence they were trying to leave behind is inextricably linked to US government policy.

The violent 1979-92 civil war, which saw civilians killed by US-trained government death squads, caused many Salvadorians to flee to America in the 1980s. MS-13 started in Los Angeles to protect the young immigrants, often living in poverty, from established gangs already operating in the area. When the US began deporting criminals back to their countries of origin after the war, Salvadorian gang members took their gang affiliations back with them. They soon took root in a country destabilised by over a decade of war.

The gangs are notoriously secretive, as are the local police force that put their lives in jeopardy trying to rein them in. Zaidi began a months-long period of research and negotiation before taking his first photograph in 2018. He captured the impact of gang warfare, from the tragic crime scenes and funerals to life in the prisons, until 2020. This project Sin Salida (No Way Out) is now published as a photo book by GOST.

Zaidi’s vision is unflinching and unglamorous, with gang members mostly shown crowded under fluorescent lights in dilapidated prisons. Normal life is only glimpsed at the margins, often in the form of grieving families. “This breakdown of social norms exacerbates the situation: young people grow up in war-like conditions and are often socialised through and into the gang,” says Zaidi. “The ubiquity of violence is devastating to regular psychological development.”

Still, there are recent indications that the tyranny of gang life in El Salvador may be lessening. Although the country still experiences unpredictable bursts of violence, the homicide rate seems to be dropping from its terrible peak in 2015, when it was double the 2018 rate.

Read more

President Bukele, who came to power in 2019, credits his own iron-fist policies for the drop in violence, although informal pacts and backstage manoeuvrings may also explain the change. Government statistics indicate the 2020 murder rate was the lowest in two decades.

However homicides are just one indication of gang control, which remains rife. “When you talk to families who have experienced this violence – murders, disappearances, extortion, death threats – you understand that most people live out their days in fear,” Zaidi says. “My hope with this work is to amplify the voices of those Salvadorans who fight for basic human rights, security and a safer life for their children and families.”

Sin Salida by Tariq Zaidi, £35, is published by GOST Books. Tariq Zaidi can be found in Instagram and Facebook

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments