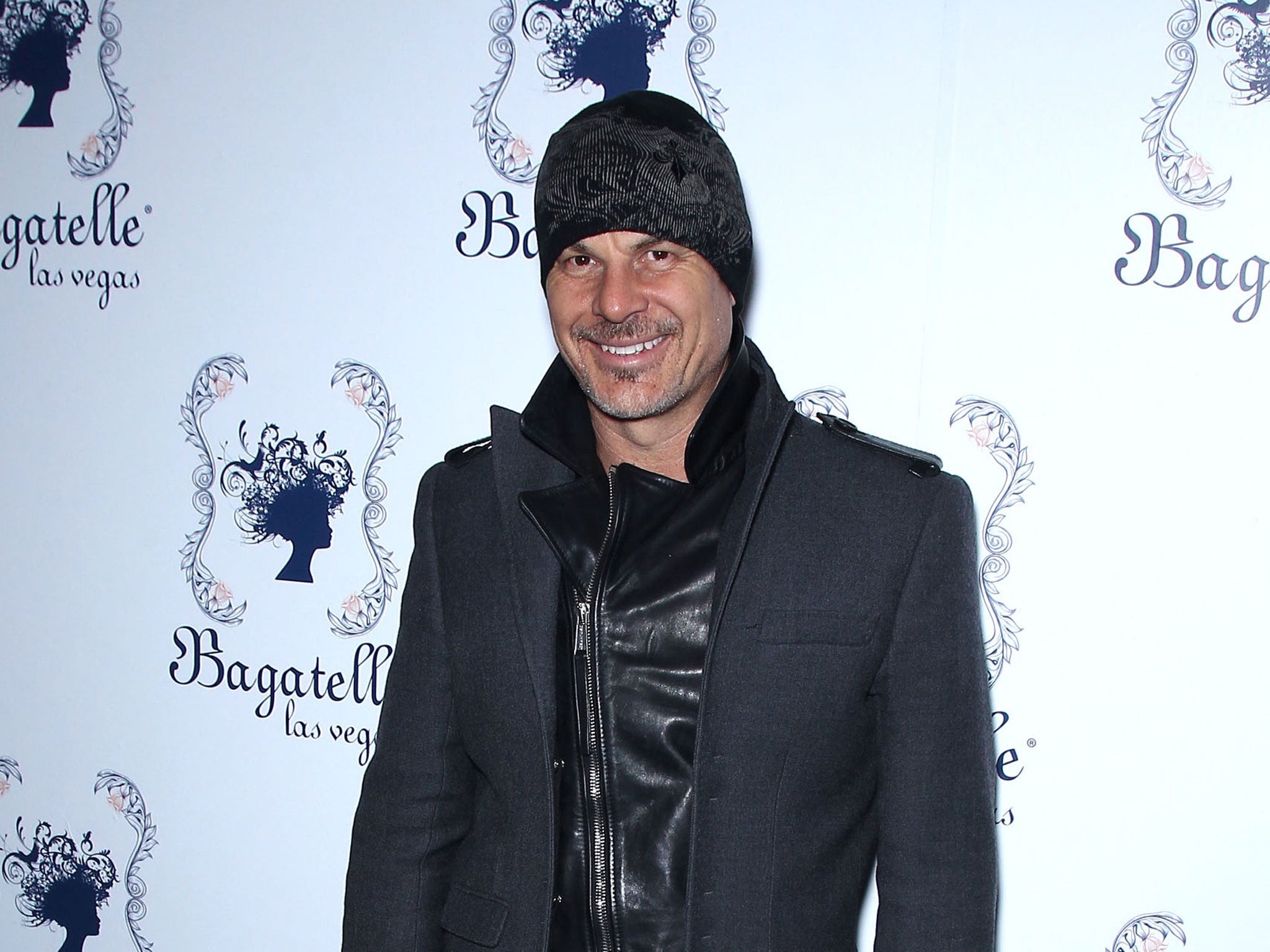

Peter Lik: The self-proclaimed 'fine-art photographer' whose work sells for millions

One of the Australian's images sold for £4m this week, but he divides opinion

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A little-known Australian photographer who looks like Crocodile Dundee and describes himself as “one of the most important artists of the 21st century” has reignited a fierce debate about photography as art after selling an image of a canyon for a record £4m.

Peter Lik’s four spots in the list of the 20 most expensive photographs sold make him the Picasso of the darkroom. But after the self-proclaimed “fine-art photographer” shot to the top this week with Phantom, a monochromatic Arizona landscape, critics have reacted variously with anger and bafflement.

“I’ve never even heard of him,” Martin Parr, the renowned British photographer, says. “It’s pretty astonishing. I’ve looked at his work today and though he’s a very good commercial photographer who can take pictures people like, he has no standing whatever in the fine-art world that I belong to.”

The sale in Las Vegas on Tuesday included two other Lik images bought by the same anonymous collector, who was vouched for by a law firm, for a total of $10m (£6.4m). The photographer, who moved to America 30 years ago, arrived in the top 20 in 2010 when he sold One, a shot of a man in snow by a river, for $1m.

“It’s an abomination,” Michael Hoppen, a leading British photography gallerist, says of Phantom, which shows a shaft of light entering a canyon. “I remember when he sold the picture in 2010, my jaw dropped. I thought, who could be persuaded to part with $1m for a piece of tat? You could have done it with an iPhone.”

Looking at Phantom, the record-breaking photograph, Hoppen, a former photographer whose sister is Kelly Hoppen, the interior designer, adds: “He’s obviously got a huge camera and must have an amazing printer, but that’s not art, it’s a function of the equipment. Art, whatever the medium, is something that moves and informs you or changes your opinion. This has nothing to do with art or creative photography, and the tragedy is that it brings the whole business down.”

But Parr, who says his works achieve maximum prices of £7,000, wonders if the opposite might be true. “It’s a good headline and can’t do any harm,” he says.

“We live in a country where photography is so underrated – there are about 60 big photography galleries in New York, and about five in the UK – so anything that promotes the notion that photographs are good to buy and sell is good news.”

The “can photography be art” question is almost as old as the camera. An artist who had joined the Photographic Society of London said not long after its foundation in 1853 that fine art should “elevate the imagination”, something that photographs, being “too literal”, could not do.

Views have been slow to change. When the National Gallery revealed its first major photography exhibition in 2012, critics pounced. Brian Sewell said the curators swallowed “hook, line and sinker the notion that the photographer is, in genius, the equal of the painter and, without questioning, promote the folly... I am with Baudelaire, who saw [photography] as, at best, art’s servant, at worst, as art’s usurper and mortal enemy.”

But few people on either side of the camera lens now question the artistry in works by photographers such as Andreas Gursky, Cindy Sherman, Edward Steichen and Jeff Wall, whose works sell for almost as much as the controversial Lik’s. “These are people who reinterpret what they see around them,” Hoppen says. “If you go to a Sherman show or look at a Steichen print, this is quality and creativity that is unobtainable to the man on the street.”

Yet, while comparing Phantom to “a posh poster you might find framed in a pretentious hotel room”, Jonathan Jones, the prominent art critic, wrote yesterday that “photography is not an art. It is a technology”.

Clare Grafik, the head of exhibitions at the Photographers’ Gallery in London, disagrees. “Art’s worth is what someone is willing to pay for it,” she says. “And if an artwork is only legitimate through the intervention of someone’s hand on material, then photography would not be alone in not fitting that categorisation. It’s a very old-fashioned idea.”

Grafik had also barely heard of Lik, who did not respond to requests for interview yesterday, but she is less critical. “All this indicates is just how broad a field photography is,” she says. “We have the works of two fashion magazine photographers in the gallery now. They were never designed to be hung on a wall in a frame, but that doesn’t mean they’re less interesting to consider as artworks... definitions restrict you and when you start to tie down what constitutes art, many things we have on at the moment wouldn’t make the cut and we would be poorer for it.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments