Norway gives Arctic foxes a helping hand amid climate woes

A network of biologists is bringing the remote canine species back from the brink of extinction – but the fight to repopulate isn’t without critics, write Lisi Niesner and Gloria Dickie

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.One by one, the crate doors swing open and five Arctic foxes bound off into the snowy landscape.

In the wilds of southern Norway, the newly freed foxes could struggle to find enough to eat, as the impacts of climate change make the foxes’ traditional rodent prey scarcer.

In Hardangervidda National Park, where the foxes have been released, there hasn’t been a good lemming year since 2021, scientists say.

That’s why the scientists breeding them in captivity are also maintaining more than 30 feeding stations across the alpine wilderness stocked with the dog food, kibble – a rare and controversial step in conservation circles.

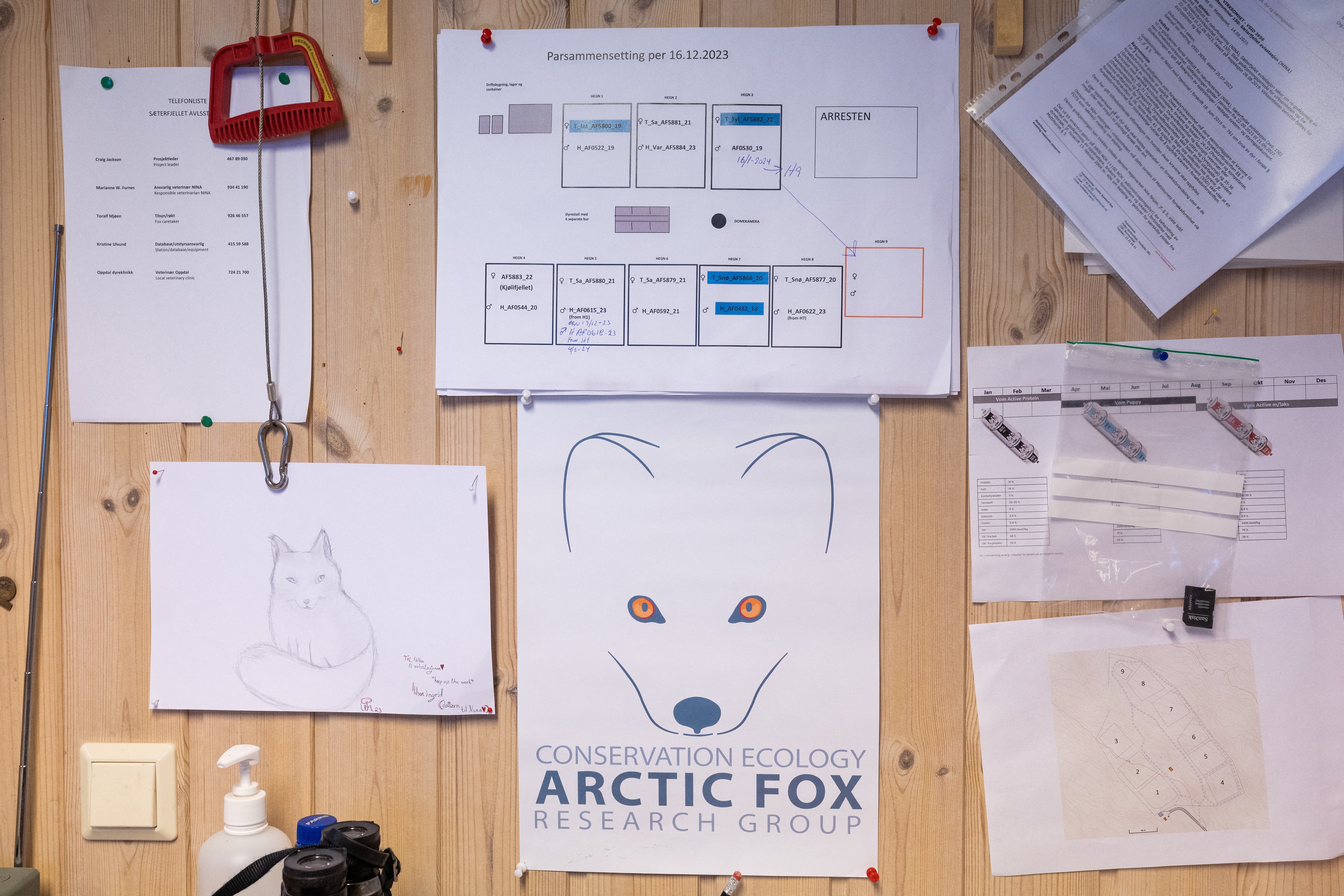

“If the food is not there for them, what do you do?” said conservation biologist Craig Jackson of the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research (Nina), which is managing the fox programme on behalf of the country’s environment agency.

That question will become increasingly urgent as climate change and habitat loss push thousands of the world’s species to the edge of survival, disrupting food chains and leaving some animals to starve.

While some scientists say it’s inevitable that we’ll need more feeding programmes to prevent extinctions, others question whether it makes sense to support animals in landscapes that can no longer sustain them.

As part of the state-sponsored programme to restore Arctic foxes, Norway has been feeding the population for nearly 20 years, at an annual cost of around 3.1m NOK (£230,000) and it has no plans to stop anytime soon.

Since 2006, the programme has helped to boost the fox population from as few as 40 in Norway, Finland, and Sweden, to around 550 across Scandinavia today.

With feeding programmes “the hope is that you can perhaps get a species over a critical threshold”, said wildlife biologist Andrew Derocher at the University of Alberta in Canada, who has worked in Arctic Norway but is not involved in the fox programme.

But with the foxes’ Arctic habitat now warming roughly four times faster than the rest of the world, he said: “I’m not sure we’re going to get to that point.”

Feeding animals to ensure a population survives – known as “supplementary feeding” – can be contentious.

Most instances are temporary, providing food for a few years to help newly released or relocated animals adapt, such as the Iberian lynx in Spain during the 2000s.

In other cases, governments might assist animals in acute peril, such as Florida’s decision to feed romaine lettuce to starving manatees from 2021 to 2023 after agrochemical pollution wiped out their supply of seagrass.

There are some exceptions. Mongolia’s government, for example, has been putting out pellets containing wheat, corn, turnips and carrots for critically endangered Gobi brown bears since 1985.

But for predators living close to human communities, that can be risky. Bears are known to change their behaviour and can associate people with food, said Croatian biologist Djuro Huber, who has advised European governments on the feeding of large carnivores.

Feeding wild animals can also propagate diseases among the population, as animals cluster around feeding stations where pathogens can spread.

Bjorn Rangbru, a senior adviser on threatened species with the Norwegian Environment Agency, said the supplementary feeding – together with the breeding programme – was crucial in raising the numbers of Arctic foxes in the wild.

“Without these conservation measures, the Arctic fox would surely have become extinct in Norway.”

The government has so far spent 180m NOK (£13.3m) on the programme – or about £29,134 for every released fox.

Some of those foxes have crossed borders. After Norwegian scientists released 37 foxes near the Finnish border from 2021 to 2022, Finland saw its first Arctic fox litter born in the wild since 1996.

But the programme is not even halfway to the goal of around 2,000 wild foxes across Scandinavia, which scientists say is the population size necessary to naturally withstand low rodent years.

Photography by Lisi Niesner

Reuters

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments