The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

‘Melania is interesting... She’s very vulnerable, always has been’

In the last five decades, there aren’t many celebrities that Jonathan Becker hasn’t photographed and he has a story behind them all. Here, he tells Zoë Beaty about his time at Trump Tower, what made Tom Cruise so cross, and why Weinstein was always a monster hiding in plain sight…

Jonathan Becker has a story to tell. In fact, he’s got quite a few – so many that, occasionally, it’s hard to keep up. Currently, we’re talking particularly about his relationship with the Trumps, a long affair documented by a catalogue of some 21 photographs in Becker’s portfolio. There’s a specific portrait he wants to talk about: Melania, dressed in a glaringly purple dress, standing next to her ominous reflection in the window beside her. To her left is a panoramic view over New York City, from the top of Trump Tower. On her right, the garish gold apartment inside. “And she’s in the corner,” says Becker. “Between a rock and a hard place.”

Back then, in 2005, Trump was just a character around town, and Melania was a socialite being photographed by Becker for Tatler. It’s a time warp of sorts – twenty years later, their story has contorted to the point that these photos (almost) feel naive in some way. But underneath the glossy finish, he tells me that he doubts much has changed about the people they really are.

“I got to know Melania quite well,” says Becker. “She’s very quiet, she’s discreet, but she has flamboyant tastes.” In the photo, taken for Tatler, her hands are up, arms guarding her chest. She looks quite vulnerable, I say. Becker’s reply is immediate: “She is vulnerable,” he says certainly. “She’s very vulnerable. Always has been.”

He adds. “Melania’s an interesting creature. She doesn’t do what she’s told.”

Becker has a backstory for every photograph that is printed in a new coffee table book of his life’s work, Jonathan Becker: Lost Time, each one as compelling as the next. The retrospective, a beautifully bound collection of 200 images spanning five decades of Becker’s spent in New York, London, Paris and Buenos Aires, contains some of the best portraits ever taken.

It’s a perfect example of why Becker’s evocative work has earned him the accolade of being one of the most revered visual storytellers of the 20th and 21st centuries.

Alongside the Trumps – Donald is captured in his element, inside their gauche, gilded apartment in Trump Tower – his work uniquely documents the beau monde. From the likes of Jean Basquiat and Roy Lichtenstein to political figures such as Nancy Reagan, Jackie Kennedy and Aung San Suu Kyi, Becker has photographed the definitive figures from every decade. There are royals from all over the world, A-list celebrities, stately literary figures. There’s not a notable person who seems to have escaped Becker’s gaze – and none that he won’t talk about.

He divulges that Tom Cruise was “p***ed off” with Nicole Kidman the night he shot her dragging heartily on a cigarette at the Vanity Fair Oscars party in 2000; he speaks about the “predatory” look he captured on Harvey Weinstein’s face as he looks over the shoulder of Léa Seydoux. “There was something monstrous about him,” says Becker. “And he does look predatory in that picture. That’s what I like about it.”

Portrait after portrait transports through decade after decade, yet, the more you look, the more it becomes clear that the most interesting picture Lost Time depicts is the one it paints of Becker himself. The story, edited by Mark Holborn, shows a man driven by curiosity and a desire to capture the reality of the world he describes as “always far more surprising than fiction could ever be, far more surreal than the surreal”.

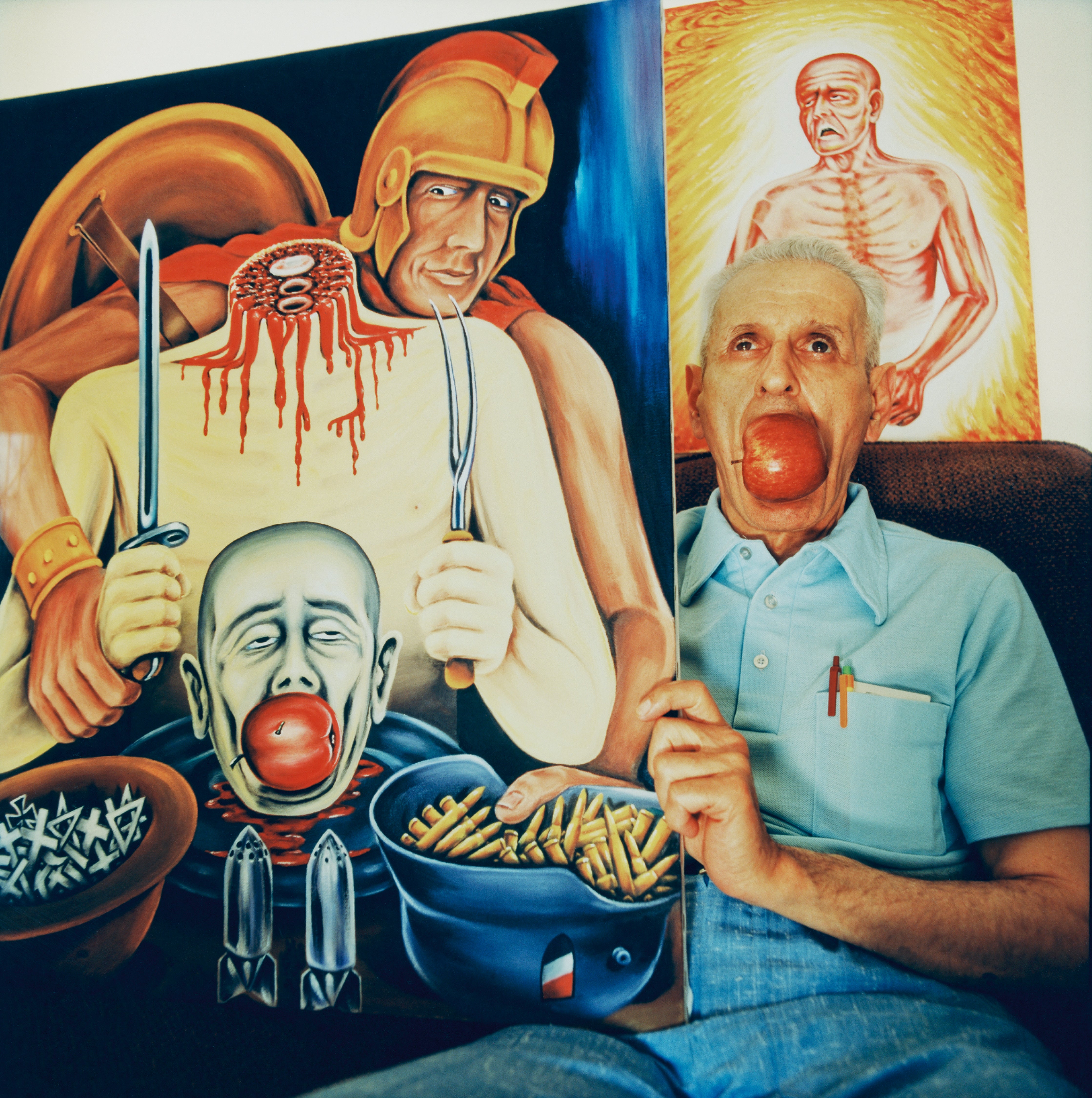

“I’m always surprised,” Becker, now 70, says of his subjects, by now in their thousands. He begins telling me about the time he pictured Dr Jack Kevorkian, who famously championed terminal patients’ right to die by assisted suicide. “He was a kind of cause celebre at the time. But as I got to know him he was a funny little man with a sense of humour and, as I learnt more, a strange thing started to appear. I was intrigued by him, and curiosity is appealing to a subject. One day he said he wanted to take me to his house and show me his paintings.”

They were “horrifying”, says Becker. “There was one of a decapitated head on a plate – his own head, and he’d stuck a wormy apple in his mouth … I thought, this man is mad.”

Becker’s portrait of Kevorkian, nicknamed “Dr Death”, who was later convicted of murder, shows him holding the picture. “It’s an extreme example of what happens in any sense of portraying someone,” he explains. “You find the truth. He was relieved this picture was taken. Because it was his story, it was the truth.”

It’s this sentiment that drives Becker’s work, no matter what tale he’s telling. He wants to capture a core truth. Like the one he recalls of a picture not featured in the book, of Donald Trump. Trump had been trying to build a golf course over a reservoir (and, of course, was prevented from doing so by environmental agencies). He blamed Wasps – White Anglo-Saxon Protestants – so Becker dressed him up like one.

“I spoke to the magazine’s fashion department which I usually avoided” – despite being innately stylish, photographing fashion and brands do not interest Becker in the slightest, I later learnt – “and I said, send me tweeds, brogues, argyle socks. He got all dressed up and looked like a giant Little Lord Fauntleroy. But he loved it. He wanted 200 prints of it. That’s when it’s really great, when people love the absurdity of their own image.”

Clearly, Trump was charmed. Unsurprising – the theatre of the absurd is an arena in which he thrives. Plus, that charm makes Becker fun to talk to. He has the distinct disposition of someone who came to success in the same way so many revered artists in the late 20th century did – in late 1970s New York, at a time when ordinary people set the city alight with vibrant new ideas and radical experimentation.

Like Fran Lebowitz, another iconic figure of the New York scene, his career essentially began in the driver’s seat of a cab. “I’d park the cab, run into a party, snap the pictures and get back in the cab and make twice as much money that night,” he says. In the beginning, it was W magazine who briefed him to take a few snaps of New York’s bohemian elite. “What it did for me was give me a kind of ease in those party circumstances, because the idea was I was doing it very expeditiously.”

Various mentors aided his skill and anchored his place in the history books. He was the protégé of Hungarian-French photographer and sculptor Brassaï, whom he credits with his early success; Jean-Paul Goude and Slim Aarons were also confidantes. His close relationship with the late creative director of Vogue, André Talley, was also of great importance to him.

Over five decades, Becker would travel the world working for the most prestigious magazines in publishing – Tatler, Vanity Fair, who hired him aged 26 to help relaunch the magazine, Vogue – but his favourite pictures aren’t the most stately in his collection.

Photographs he took during his early days in New York at the famous restaurant Elaine’s – owned by his dear friend Elaine Kaufman, where the likes of Woody Allen and Norman Mailer hung out – he says are his best. He’s most lively when we talk about candid shots, like one of Mick Jagger leaning into a whispered conversation at a glamorous-looking party. “These pictures were what I thought I got good at,” he says. “I wasn't there to just take the pictures of the celebrities: I was there to take portraits of people who happened to be there and be really intriguing, in interesting circumstances.”

He uses a piercing shot of David Bowie giving a sultry side-eye next to Olatz Schnabel, the Paris-born former model, as an example. “There’s so much movement in pictures like this,” explains Becker. “The feeling from Bowie is immediate – it feels like it’s telling a whole story all at once. It’s because he was feeling comfortable around Schnabel and those big knockers. Oh, wait, I can’t say that,” he quickly adds – a man of a certain time, perhaps.

It’s not the first time that Becker self-corrects throughout our chat, which rolls well over the allotted hour – a rarity in an era where celebrities and artists are so heavily trained and “managed” that it can feel almost impossible to really know them. Becker is refreshingly different in that sense; he’s bluntly honest and (mostly) unfiltered.

“Well, at my own peril, I think,” he says, audibly taking a drag on a cigar. He no longer drinks because of the headaches it gives him but also because, “when I drink a little, I start saying things for the purpose of p***ing people off. Which I enjoy,” he adds. “It’s very childlike. It’s not a good thing.

“Seeing people turn beet red with rage, fire coming out their nose and ears and just because of things you say… I find that so kind of empowering. But I don’t do it unless I’m drinking, and I’m not drinking.” So I’m safe, then? “Yes,” is his wry reply.

Becker has rarely stopped working since he began – but now, the worlds he has captured in Lost Time really do feel quite lost. “It all seems awfully chaotic,” he says of modern celebrities. Social media is “such a weird, meaningless juxtaposition of things that can distract you”, he says. “You know, it’s utterly worthless.” Plus, he’s always disliked self-promotion and parties. “I prefer to be more unknown and discreet.”

As we sign off, he has one last story: his own. “Every time I look at the book, I learn something about myself, almost like it’s someone else’s life,” says Becker. “It sounds corny but it’s like what they say when they get the Oscars – if you keep at it, it’s amazing what piles up.

“The thing that comes out, that you realise all these years – decades – later, is that I’ve been singularly and fervently devoted to the pursuit of my own curiosity. I don’t know how I could have had, at such an early point of life, the faith or the courage to do these things. And, I don’t even know that faith or courage had anything to do with it – maybe faith,” he adds. “Moreover, it was about need. I didn’t have a choice. I was never trying to prove anything to anyone, I was just trying to make it work.” It did.

‘Jonathan Becker: Lost Time’, edited by Mark Holborn, is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments