Lockdown Bristol through the eyes of a key worker

Working as a bicycle courier during Bristol’s first coronavirus lockdown, photographer Chris Hoare documented the city’s empty streets on his daily deliveries. His new book ‘Keywork’ reflects on the pandemic’s strange mix of isolation and solidarity

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For Chris Hoare, bicycle courier work was a back-up job, something he started to support himself through his photography MA. But as the coronavirus pandemic engulfed the country in the spring of 2020, it became increasingly hard to find photography jobs. He returned to courier work in his hometown of Bristol. “My other freelance work mostly stopped. It was one of the only things that I could keep doing to earn a living,” he says.

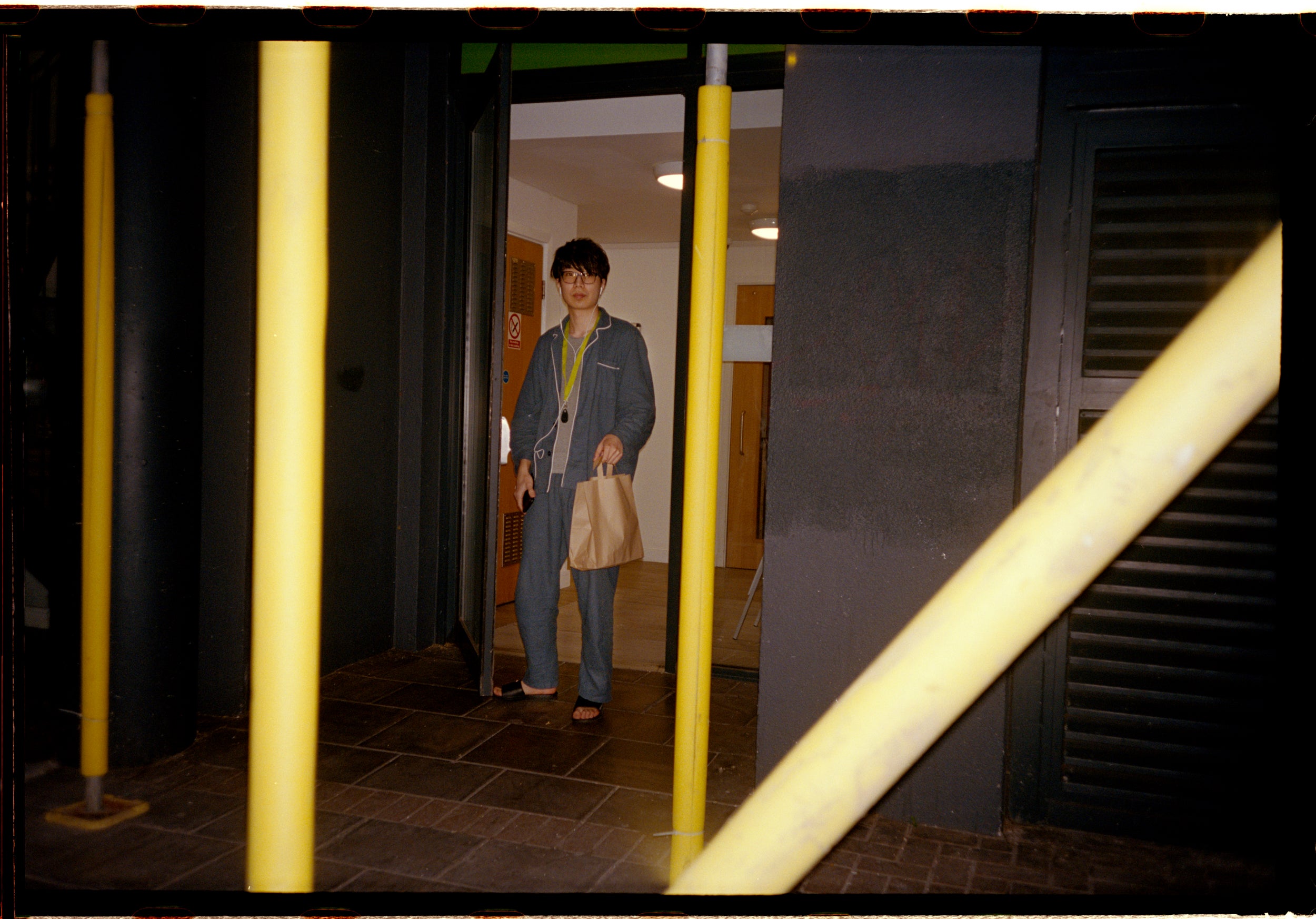

He began photographing the eerily empty city in the grip of lockdown on his daily deliveries. Despite the pandemic, people seemed happy to have their picture taken from a distance. “I would explain that I was working as a bike courier, but that I [also] worked as a photographer and wanted to make a record of the strange time we were all going through, [and] most people understood this,” he says. “Many of the other images that I made were fleeting moments, made at a distance, in an attempt to capture something of the atmosphere of the time.” These photographs are now collected in Keywork, a new book from Besides Press.

His work, taken in a verite snapshot style, reflects the empty, quiet chaos of the first months of the pandemic, and the strange mix of isolation and solidarity in the air. With many families, students and workers sequestered inside their homes, the people he saw remaining on the street began to fall into two categories: the homeless and the “key workers” – a concept that shot to prominence during the pandemic. His photos show the clear divide between the recipients of his food deliveries, the lauded (though often poorly paid) key workers and the largely forgotten homeless people remaining outside in the strange spring wasteland to brave a pandemic .

The city has long struggled with housing issues. Bristol council counted 98 rough sleepers in February 2020, and this year it was reported that the number of single people in Bristol requiring temporary housing more than tripled during the pandemic.

“It seemed to be a strange time for [homeless people],” Hoare reflects on the early days of the pandemic. “For the first time ever they were thrown a lifeline by the government – being offered a bed in a hotel. However, some of the people that I talked to had chosen not to take them up on that offer, it seemed the hotels were rife with drug taking and other temptations that were best avoided by those [wanting] to stay on the straight and narrow. Everyone I talked to explained that the money they would usually get from begging had dried up almost immediately during the lockdown, and I noticed many of them sticking together much more than I had seen before.”

As the city emerges from lockdown – and as Hoare is able to step back from courier work and return to photography jobs – he reflects on the meaning of key work. “Many jobs that are vital and which we all benefit from are still deeply under-appreciated,” he says. “As things go back to normal, that small segment of time where those who performed key work were temporarily thrust into the spotlight seems to have faded. We all appreciate the NHS and the workforce that were on the frontline of the virus, but all of the less obvious roles such as supermarket workers or people cleaning our streets have yet again been forgotten.”

‘Keywork’ by Chris Hoare. Published by Besides Press, £16

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments