Dorothea Lange: An alternative look at the photographer who humanised the Great Depression

Her iconic photograph ‘Migrant Mother’ cemented Dorothea Lange’s place in history. Now a new exhibition and book seeks to expand the way we see Lange’s substantial body of work

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Dorothea Lange is best known as a documenter of America’s Great Depression. Over the second half of the 1930s, she worked for the Farm Security Administration, capturing the plight of migrant labourers, sharecroppers and the rural poor with an unflinching empathy.

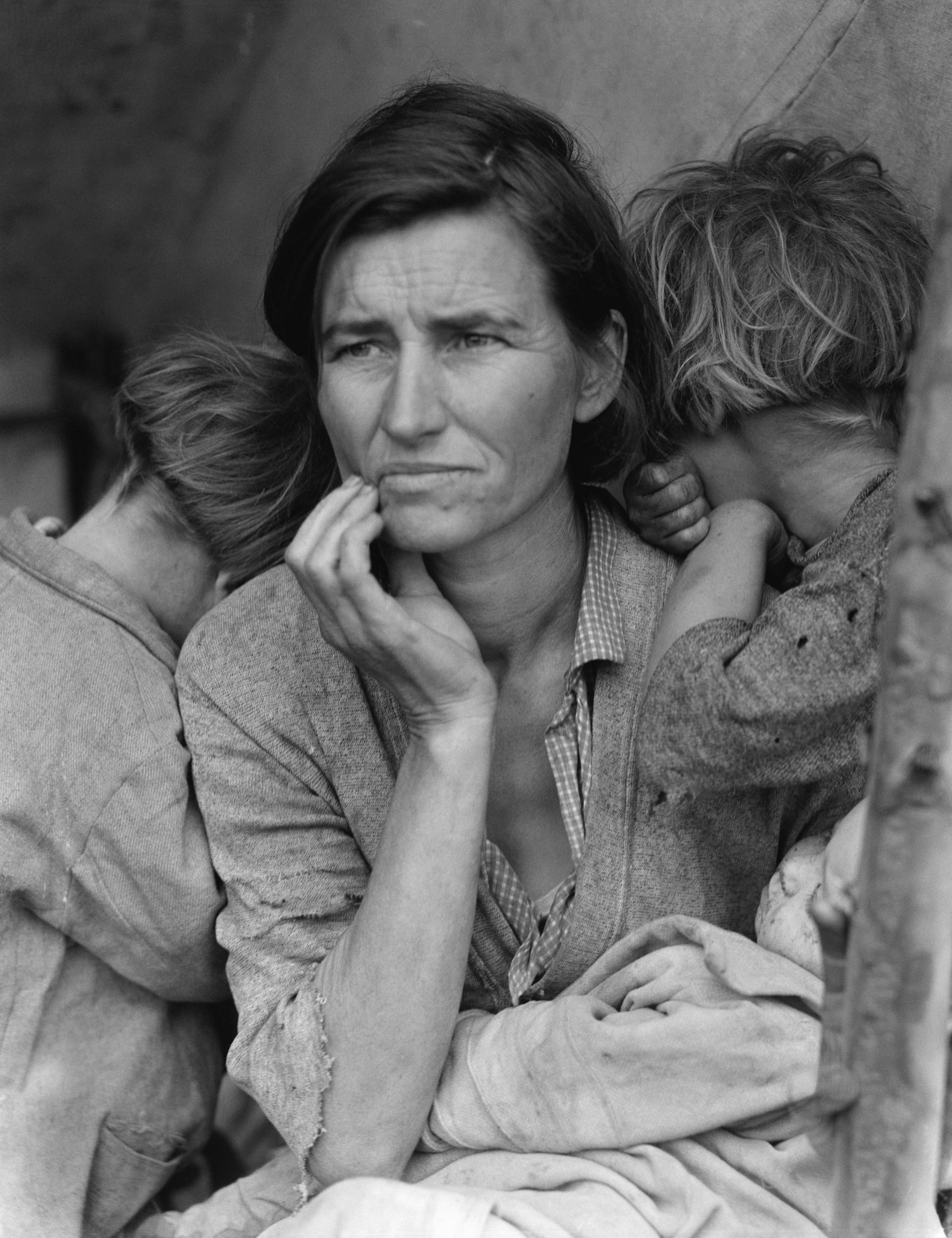

Her most famous picture is Migrant Mother, a closely framed portrait of a careworn farm labourer, her dirt-smeared children hiding their faces in her shoulders. Taken in 1936, Migrant Mother has become one of the most famous photographs ever, credited by TIME magazine for doing “more than any other [image] to humanize the cost of the Great Depression”. When it was first published in a newspaper, the State Relief Administration delivered food rations to 2,000 migrant workers the next day.

Although Migrant Mother cemented Lange’s place in history, its oversized presence has tended to obscure the rest of her work. Now an exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), and a new book from MACK, seek to expand the way we see Lange’s substantial body of work.

In 2017, artist Sam Contis discovered a trove of Lange’s negatives and contact sheets at the Oakland Museum of California, the majority of which had not been seen before. This unexplored archive, featuring pictures of Lange’s family, travels and studio portraiture, recasts her work. Untethered from the heavy responsibility of telling the stories of people in dire situations, they delight in the texture of cotton shirts and weathered hands, more ambivalent and playful than her state-sponsored work.

“The archive felt very alive and open to me,” Contis told The Independent. “I had never felt that with another artist before. I was struck by her interest in gesture, her obsession with hands, the fragments of bodies, the ways she conveys intimacy in her photographs. There’s also a beautiful choreography and sense of movement in her work, and even in the way she presents her work, that I also hope to convey in mine.”

Contis has included her research in the upcoming MoMA exhibition of Lange’s work, and her new book Day Sleeper collects her archival discoveries, which are presented along with Lange’s captions and fragments from a 1956 interview. “I wanted to reveal a largely unknown side of Lange,” says Contis, “but also do it in a way that felt fresh and reflected how contemporary I saw the individual pictures to be. In my book, Lange’s photographs are loosened from their original, temporal context. I wanted Lange’s photographs to feel alive to this present moment in a more unexpected way.”

The book is centred around the figure of the sleeper, a recurring subject for Lange, who struggled throughout her life with fatigue, chronic pain and disability after contracting polio as a child. The sleeper has a paradoxical relationship to photography – a sightless figure in a visual medium, it suggests a sense of impenetrability. “As viewers, we can’t see what the sleeper ‘sees’; we’re cut off from their interior vision, even though we can look as freely as we like without our gaze being returned,” says Contis. “In a way the book invites the viewer into this hidden, interior world: the sequences of images can be read as a sort of fragmented fever dream.”

Lange, who died in 1965, was interested in seeing the unseen, and “wanted to explore photography to its limits, whatever those limits might be,” says Contis. It seems appropriate her work is now being looked at from a new perspective, expanding the limits of how we view this celebrated photographer.

‘Day Sleeper’ by Dorothea Lange and Sam Contis is available from MACK; Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures is at the Museum of Modern Art in New York until 9 May

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments