The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

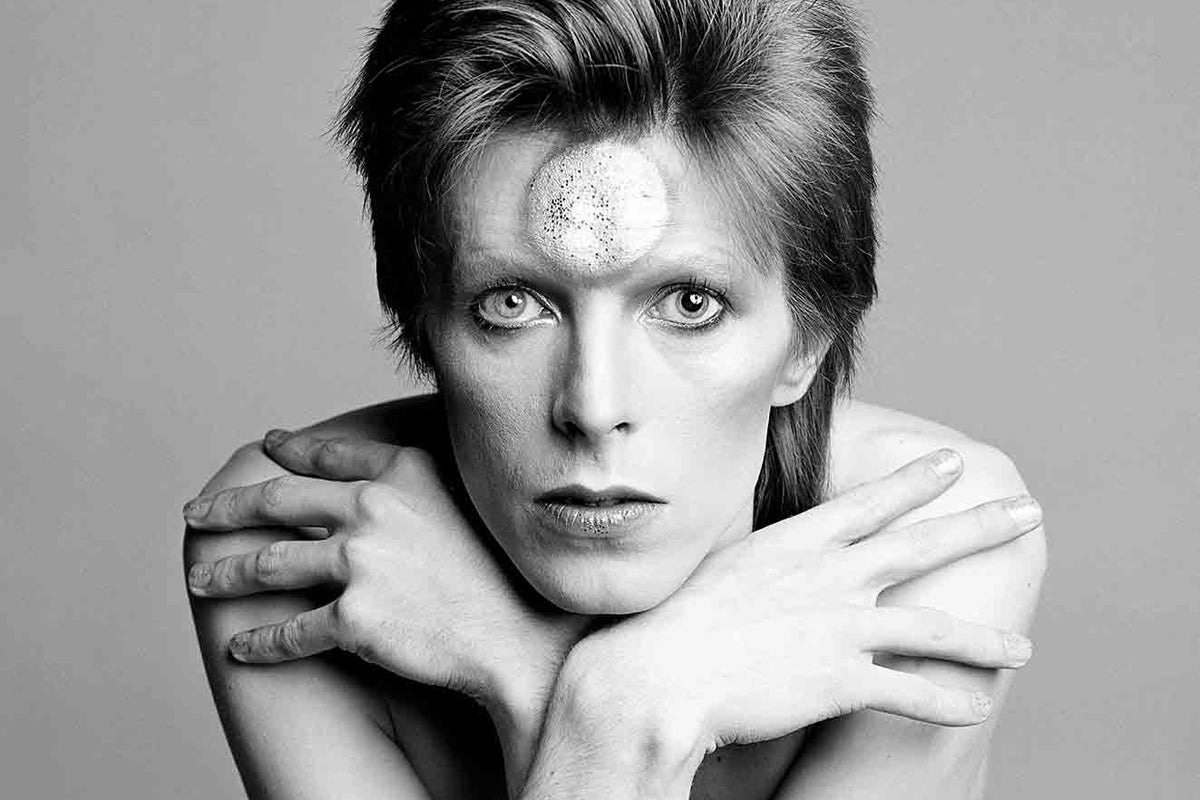

The making of an icon: David Bowie’s life in photos

A new book showcases the musician’s photographers from his teenage years onwards, examining how he constructed his ever-shifting public image

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Who has been more influential on popular music than David Bowie? His ever-shifting personas, musical innovations and transgressive strangeness over a decades-long career broke new ground for what we think of as possible within popular music.

Image was always crucial. And to achieve his visual fluency, Bowie needed collaborators. A new book, David Bowie: Icon - The Definitive Photographic Collection, gathers images and written texts from the photographers who captured Bowie from his very early career right to his last period of illness. The book explores how they documented – and in some cases, defined – one of music’s most enduring stars.

Photographer Gerald Fearnley, whose brother was a bass player in Bowie’s backing band, remembers Bowie hanging out at his house in 1966. “He used to play with the children, games of Monopoly or teaching them how to play the penny whistle,” he writes in David Bowie: Icon. “David was great with the kids, very pleasant, always polite.” He captures Bowie at the time of his 1967 debut album – a flop, as it turned out – in an ill-fitting jumper and mime makeup. Not quite a fully formed artist, he’s clearly bursting with ideas and a love of performance.

Two years later, he’s on the edge of a creative breakthrough. Photographer Vernon Dewhurst remembers meeting him in a South Kensington flat in the spring of 1969. “David is sitting crosslegged on the floor holding something he calls a stylophone that emits a strange synthetic metallic buzzing sound,” Dewhurst recalls. “He’s accompanying himself with a small cassette recorder on the floor next to him and he’s singing about ‘Major Tom’.” Dewhurst would go on to shoot the cover of his second album, which would contain the song “Space Oddity” – Bowie’s first hit.

What emerges is a portrait of Bowie not only as a great artist, but as an unfailingly kind and generous man. Often, he would act as a mentor figure to young photographers, taking a chance on artists early in their career, and forming long-term collaborations. He was also an endlessly fascinating subject – photographer Mick Rock remembers photographing Bowie as Ziggy Stardust, a period which covered 22 months and 74 different outfits. “I’m one of the world’s actors. I’m an exhibitionist, a peacock. I like showing off. Freud would have had a heyday with me,” Rock recalls him saying.

While much of Bowie’s ground-breaking styling was deliberate, some came about purely by circumstance and hasty, collaborative moments of improvised genius. Photographer Justin de Villeneuve recalls arranging a shoot with Bowie and the supermodel Twiggy for the cover of Vogue magazine. "I realised we had a problem," he says. "Twiggy and myself had just returned from the Bahamas and she had a dark tan. David was as white as a ghost. They looked weird together."

He and make-up artist Pierre LaRoche decided to embrace this dissonance and draw masks on their faces of the same colour – one of the strange, otherworldly images would end up as the cover of Bowie’s 1973 album Pin-Ups instead of on the magazine cover. "Vogue never spoke to me again!" De Villeneuve says.

Despite his chameleonic tendencies, Bowie was also self-referential, and ideas and themes could be revisited and elaborated on over and over again. Photographer Steve Schapiro recalls a 1974 shoot where Bowie painted his clothes and his set with elaborate stripes and circles as he and his crew watched on, amazed. “I learned later was the diagram for the Kabbalah’s Tree of Life,” he says. “David was versed in all kinds of spiritual philosophy. Everything had meaning for him.”

Bowie would recreate the painted stripes again – for the final music video released in his lifetime, 2015’s “Lazarus”. “In Bowie’s life there were no coincidences. There is no question that the Kabbalah was spiritually important to him,” says Schapiro. “He saw his life itself as a work of art.”

David Bowie: Icon - The Definitive Photographic Collection is out now from ACC Art Books

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments