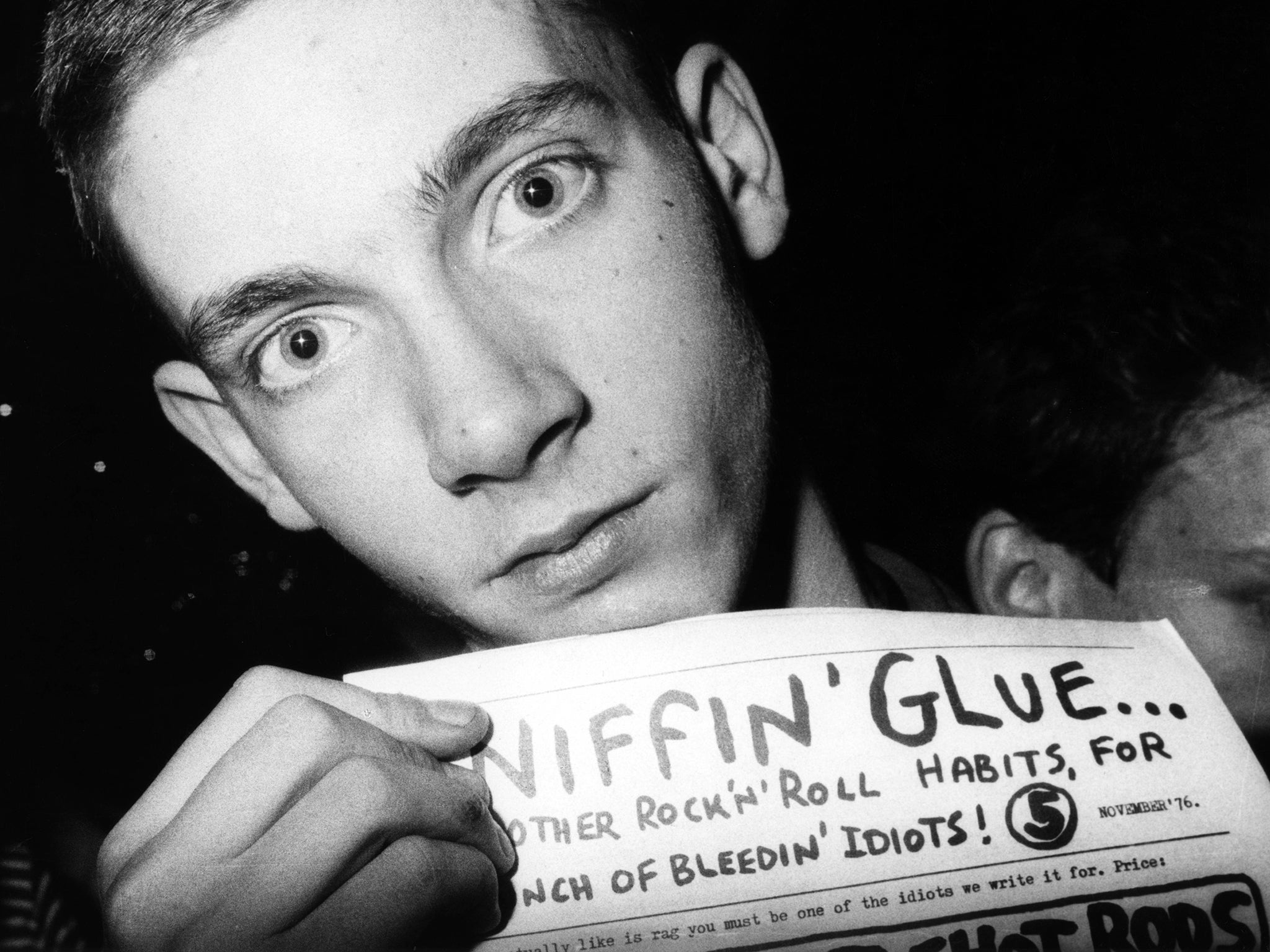

Sniffin’ Glue: A fanzine that epitomized punk

It’s UK punk’s 40th anniversary year – sort of – and among the work being celebrated is ‘Sniffin’ Glue’, the photocopied publication that embodied the movement’s high, heroic era. Founder and editor Mark Perry shares his memories

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Dateline: sometime in London 1977, in a basement club on a corner site at the top end of Neal St near Shaftesbury Avenue.

Location: the Roxy, the punk venue which took on the name of the space’s previous occupant, a gay disco. On the street above, fruit and veg from Covent Garden market stalls come to die, slowly, in the gutter. In the toilets below, young (and not so young) women and men take drugs – snorting amphetamine sulphate, mostly.

Onstage is Paul Weller, of the Jam. Weller is at the microphone, hot and bothered. He has a pamphlet in his hands. He is not happy about something written in it, about him and his band. He tells the crowd this. And he sets fire to the paper. A knowing bit of stagecraft, this: think Hendrix, with his Stratocaster and a can of Ronson lighter fluid. Also, a symbol of the times.

Punk was – not exclusively, but widely – a world of true believers. From south London to west Londonderry came grouplets of purists, with fine-tuned doctrines about what constituted real punk. Some condensed their credos into fanzines. That was what Weller was putting to the flames, the latest edition of punk’s defining fanzine, Sniffin’ Glue.

Now, all these decades later, punk is being celebrated across London. It’s a 40th anniversary thing (though no one who was around in punk’s heroic era seems to know what in particular it’s an anniversary of – the first Sex Pistols shows were in 1975, for example). One event in these celebrations is a panel discussion of Sniffin’ Glue at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. It’s a fine and fitting place. Punk was always about art as much as music: one of The Clash’s earliest shows was at the ICA and Patti Smith was in the audience, entranced by the cavernous-cheeked beauty of Paul Simonon.

Now it will welcome Sniffin’ Glue’s founder and editor, Mark Perry. A bank clerk from Deptford, son of a docker and enthused by the new music he heard around him, Perry set up his fanzine in the spring of 1976, taking its name from a track on the first Ramones album. (As for glue sniffing, let’s call it an ancient self-medication practice: you tipped some glue into a container of some kind, maybe a paper bag, cupped it to your face, inhaled the fumes and let them mess around with your nervous system.)

Anyway, Perry typed up his thoughts on a plastic typewriter, a toy almost, and took the pages down to a local photocopy shop. He ran off as many copies as he could afford, stapled them and sold them at gigs – in all, maybe 100 copies. In the style of the day, he gave himself a new name, too, the Ballardian Mark P. That little photocopied fanzine of his was the printed embodiment of the high, heroic era of punk. There were only 12 issues – the last was in July 1977 – but Sniffin’ Glue was the photocopied paper of record, spanning the era from the Sex Pistols at the Nashville to the Clash signing to major record label CBS. After that came the decline, the fall, etc etc. To true believers, anyway.

Actually, Sniffin’ Glue wasn’t the first fanzine by any means. There had been fanzines since the 1950s, home-spun outlets for the thoughts of science-fiction fans, trainspotters and record collectors. It wasn’t even the first punk fanzine: Legs McNeil’s New York Punk had been up and raving for a couple of years. Nor, contrary to (nearly) all reports, was it the fanzine which ran the advice: “This is a chord. This is another. This is a third. Now form a band.” It wasn’t even really a magazine – the writing was never all that. But it was a call to arms.

That was its significance; that and the way it looked, a paper-and-print equivalent of those art-school Roxy nights. “It was the best I could do,” says Perry (who was always the sweetest of men). He had that children’s typewriter, “something your mum might have bought you”, and he had a felt-tip pen and a ruler. “And I approached it almost like a school project. But I was really into magazines. I knew the way they were put together.” So, unlike other punkzines, it had proper headlines and a contents page.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Also at the ICA panel will be Toby Mott, one of punk’s leading ... well, curator is probably the best job description. He has a large collection of punk fanzines, posters and ephemera that he exhibits (and packages for sale in facsimile) around the world. He says: “Mark Perry took it on to himself to document punk. He felt the need to create a voice for it. He was part of it, looking out, not in. That’s why it’s important: why it is a reference point and why we are doing the ICA.

“Mark had the visceral drive to make a visual record of punk. It’s punk journalism. It’s the one fanzine everyone knows.”

Toby was a teenage punk himself. He celebrated his 13th birthday at the Roxy, and, “My world started to change. I was immersed in punk, excited by the music and culture. The immediacy of it visually drew me in as much as the music.”

By the time of its last issues, Sniffin’ Glue was something of a success, selling up to 15,000 copies. “If I had a business head, I’d have made a mint,” says Mark. By issue eight, it was professionally printed, though not bound: “We’d have a stapling party. A crate of beer. Me. Danny Baker [a school friend of Mark’s and also deeply involved in the fanzine’s founding and flourishing]. Plus a few mates. All night.”

Perry is proud of what he (and his fellow staplers) achieved. “From issues one to seven, it was undiluted, right on the ball, crucial stuff, authentic. It was bloody good. At a certain point in time, it was the best rock and roll magazine in the world.” Then it wasn’t.

“The last issue was awful. It was rubbish” – so he shut it down, suddenly, and in disappointment at how things had gone, both with the music and his fanzine. “People sometimes don’t know when to stop. They put out great albums. Then instead of calling it a day, they go on and on. Sniffin’ Glue had done what it set out to do.”

He moved on, becoming a player, creating his own band, ATV. They did well on the indie circuit and charts, without ever troubling the Top of the Pops bookers. He set up a record label, which gave the world the Cortinas and Sham 69. “I’ve scraped by over the years,” he says.

A decade ago, he left London. “Couldn’t live there any more.” He went west, first to Portsmouth, then, two years ago, as far west as you can go without setting sail for the Americas – to Penzance. He’s now a grandfather, pushing 60, a “house husband” on his second marriage with two young children to take and fetch from school. “I’m cool, really. I feel very at ease, with nothing to prove. I’m glad Sniffin’ Glue stopped when it did. That’s why it’s become a legend.”

From that far western fastness, Perry does the occasional gig with ATV. Unlike Toby, he doesn’t own a single copy of Sniffin’ Glue. (“I kept giving them away.”) He still has his moments of punky, spunky wrath, though. When NME became a free magazine, he shared the sound of his fury on Twitter: “If the owners/publishers of the NME had any balls, they would slag the whole music business off in one last glorious issue & then piss off.”

And, oh, one final thing. Mark, did you ever actually sniff any glue? “Once.” Four or five issues in, he decided he should perhaps learn about the inspiration for his fanzine’s name. He went down to his parents’ Deptford flat – they were on holiday. He and his friend Steve Walsh put on Hendrix’s Cry of Love album. (“Why it wasn’t the Ramones? I don’t know.”) They opened up a tin of model aeroplane glue. They sniffed deeply. And ... ? “I hated it. An hour later, I had a banging headache. I wish I hadn’t even tried it.”

Punk Publications: Mark Perry in conversation with Toby Mott is at the ICA at 6.30pm on Wednesday 11 May

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments