Sinéad O'Connor on religion, dealing with pain and the right to be forgotten

She can be incredibly calm. But she can also explode. The singer talks to Geoff Edgers

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Sinéad O’Connor’s office is a glass, pentagon-shaped porch that’s also the entryway to her house. Most days, before the sun rises over the Irish Sea, she’ll be sitting there, smoking a cigarette, nursing a sugary cup of coffee or shuffling through her iPad. She may even pick up a guitar.

When the water ripples in the wind, the spot can be hauntingly beautiful; Ulysses sprung to life. Not that O’Connor, born just four stops up the train line in the Dublin suburb of Glenageary, feels particularly romantic about the setting.

“I f****ing hate living in Ireland,” she says. “My spiritual home is America. I know that my stork should have dropped me in America. But he got drunk in Dublin. It’s freezing, it’s miserable. Everything’s really expensive. I love America, but I can never leave Ireland. I wouldn’t leave my grandchildren or my children.”

There are four children, a pair of grandchildren, four ex-husbands and an ex-boyfriend, Frank, who lives a short walk down Strand Road with their son, Yeshua, 13. There is her father, a sister and three brothers, all within a drive. They know her not as the pop star who rose to fame singing “Nothing Compares 2 U”, but as a witty, compassionate, difficult, fearless, playful and unpredictable woman who has struggled, personally and professionally, ever since she ripped up that photograph of the pope on Saturday Night Live in 1992. And they remember the last time O’Connor left home.

In 2015, doctors in Ireland performed a radical hysterectomy to relieve O’Connor’s chronic endometriosis. But the procedure pushed her into premature menopause, which went undiagnosed and unmedicated, she says, and made her go “completely mental.” She moved to Chicago, where she had friends, then moved to nearby Waukegan, Illinois, lived in a motel and volunteered at a veteran’s hospital. As her depression deepened, she headed to San Francisco and checked into a well-respected treatment centre. She eventually landed in a New Jersey Travelodge, where, in August 2017, O’Connor posted a 12-minute plea on Facebook referencing suicide attempts and intense loneliness. That led to an ill-advised appearance on Dr. Phil.

John Reynolds, her first husband and longtime producer, flew to the States and brought O’Connor home to Ireland. And with that, one of contemporary music’s greatest and most original artists seemed to vanish.

But last month, O’Connor, 53, quietly travelled to the West Coast for the opening leg of a mini tour, eight club shows spread over 12 days. They were a first step to reclaiming a career virtually abandoned during the years of turmoil, familial conflict and cancelled gigs. All seemed forgiven. Crowds were spellbound as O’Connor, in bare feet and a hijab – she converted to Islam in 2018 – mesmerised them with a 17-song set that stretched across her career.

“To say it was religious would be an understatement,” said Bikini Kill’s Kathleen Hanna, who saw the 9 February performance at the El Rey Theatre in Los Angeles.

Backstage after the show, booking agents huddled with O’Connor, plotting a potential autumn tour to mark the 30th anniversary of her influential album, “I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got,” which included her number one cover of the Prince-penned “Nothing Compares 2 U.”

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

She sat there quietly. Even as O’Connor finishes a memoir aimed for the spring of 2021, starts work on her first album in years and awaits the second leg of a tour – a string of sold-out east coast shows, which have been postponed due to coronavirus concerns – there is a bigger project underway. How to live.

There are still moments when O’Connor will break down, either in fury, tears or a kind of self-loathing. But during her most recent hospital stay, which ended last May, she learnt an important concept, which has become her mantra: radical acceptance. As a girl she suffered abuse from her deeply religious mother that remains with her decades after her mother’s death. In the past, she’s tried to fight and deflect it, sometimes by lashing out at others. She’s learned that this doesn’t help.

“Because that kind of pain doesn’t go away,” O’Connor says. “You only learn to live with it. Music is where I can manage it.”

She can be incredibly calm and patient. She can also explode. She can speak eloquently about Jesus or the Koran or go blue enough to make Amy Schumer blush, sometimes in the same conversation. She can be shy and insecure. And yet she didn’t hesitate to stare down the cameras on American television to call out one of the most powerful men in the world.

“It’s all soul,” says Bob Geldof, the Live Aid co-organiser and Boomtown Rats frontman who grew up in the same neighbourhood as O’Connor. “It’s a troubled soul and it ekes pain and an attempt to find an understanding through her voice and through her music. The pain gives rise to a great anger, which may not be understood at all. [People] don’t quite understand the intensity or how a personal pain translates into a sort of empathetic rage. The point is, you don’t have to. You can just listen to one of her songs.”

The songs. Highly literate, with references to Yeats, Alex Haley and the Old Testament. A blend of fact and fiction. Fearless, whether documenting racism, political hypocrisy or a bad boyfriend.

Michael Stipe remembers being deeply influenced by O’Connor in the late 1980s. He ended up adopting her mannerisms for his own performance in R.E.M.’s video for “Losing My Religion”. He also covered one of her songs, “The Last Day of Our Acquaintance”, in concert.

“In my timeline, there is a direct line from Patti Smith to Sinead O’Connor,” says Stipe, invoking the 1970s punk poet laureate. “So many people have lifted from her, from me to Miley Cyrus. She’s one of our great living icons.”

That’s when she decided she was going to use her promotional appearance to deliver a political message to one of her frequent targets, the Catholic Church

It may be hard, today, to understand just how shocking it would have been to encounter O’Connor when she first landed in the late 1980s. This was before Courtney Love, Alanis Morissette, riot grrrls, Liz Phair or Lilith Fair. With rare exceptions – Madonna, Annie Lennox – the women on MTV either played candy pop or served as eye candy for creepy, hair metal bands. O’Connor, still 20 when her debut “The Lion and the Cobra” arrived in 1987, could sing with anyone, sliding from the most delicate phrasing to full-throated, octave-leaping howls. She wrote one of the most heartbreaking political songs of the moment, “Black Boys on Mopeds”, and set a 17th-century poem to the beat of James Brown’s “Funky Drummer”. The stunning video of “Nothing Compares 2 U”, largely a close-up of O’Connor’s expressive face, made her the first female artist to win MTV’s video of the year.

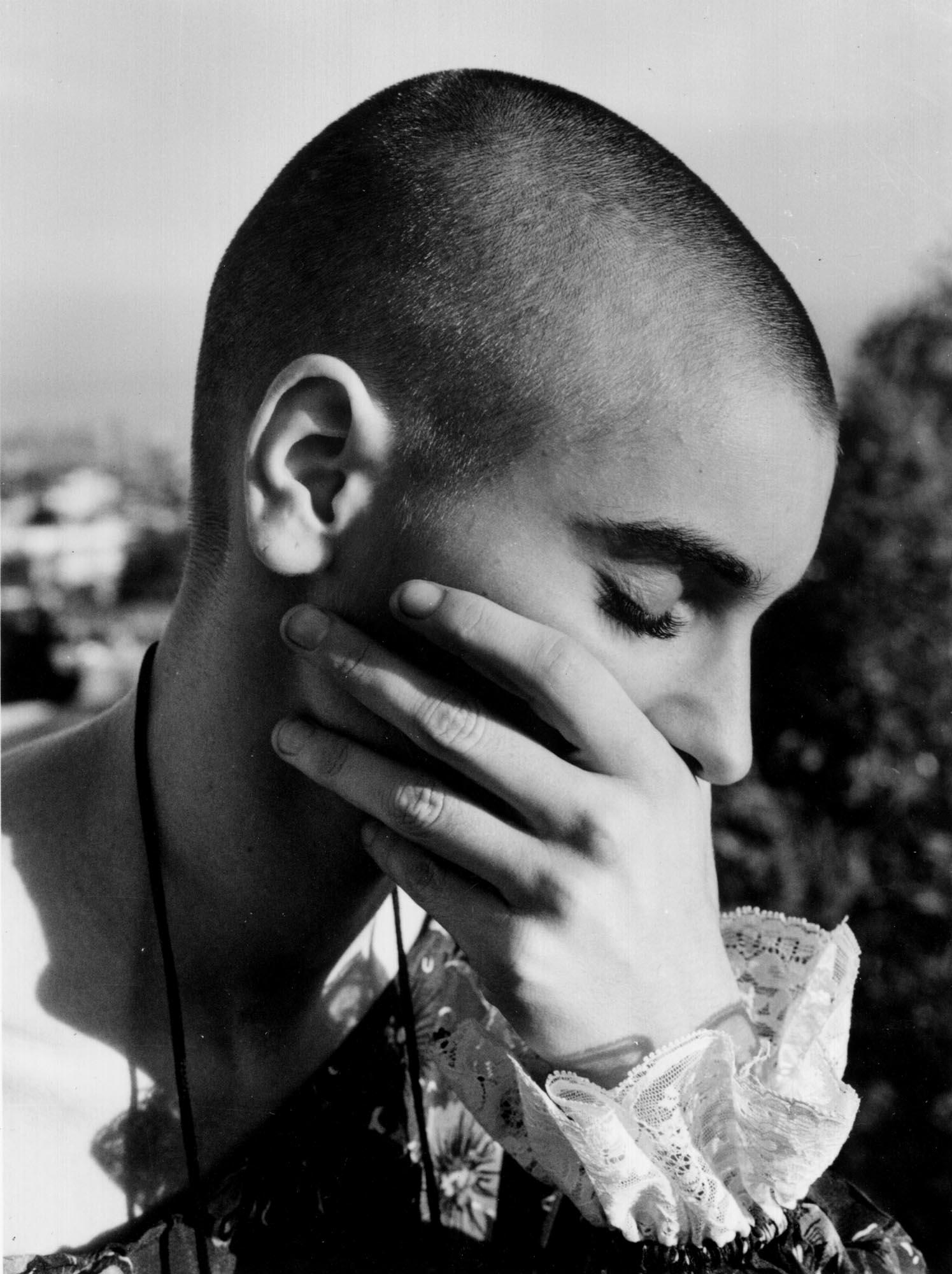

And her appeal was about more than music. There was also the look. Buzzed head, Doc Martens, eyes steely and intense except when she broke into a mischievous, dimpled smile. As if there was a joke that only she understood.

“Her voice made me feel like I existed in the larger world,” says Hanna, a college student when she got her first O’Connor tape. “She could sing something with lots of pretty parts but also you could hear rage and sexuality and humour.”

Fiona Apple was 11 when she watched the Grammys on TV in 1989. O’Connor performed “Mandinka” alone onstage, wearing a bra top and her son Jake’s sleep suit tucked into her jeans.

“She inspired me,” Apple says. “She showed me how to be unadulteratedly yourself and just be free.”

In late February, O’Connor was inspired to write a song called “Horse on the Highway”. This raw, unreleased demo was recorded in her house in Ireland.

O’Connor says her proudest moment remains her most famous, that 1992 appearance on “Saturday Night Live”. That’s when she decided, without telling the show’s producers or her publicist, she was going to use her promotional appearance to deliver a political message to one of her frequent targets, the Catholic Church. This was more than a decade before widespread reports in the American press about the sexual abuse and cover-ups by clergy. By then, in Ireland, O’Connor had already seen smaller reports of the behaviour.

There have been times when O’Connor has been eager to call out those she felt wronged by. The list of targets is long, including family members, managers, friends, Bono

After performing Bob Marley’s protest song, “War”, O’Connor lifted a photograph of Pope John Paul II to the camera, tore the picture into pieces and declared “fight the real enemy”.

The camera cut away in silence. That week, O’Connor was attacked in headlines (New York Newsday: “No hair, no taste”), her records were piled up and steam rolled in Manhattan and, at a sold-out Madison Square Garden tribute to Bob Dylan, angry shouts drove her off the stage.

O’Connor was thrilled this month when Time Magazine named her one of its 100 Women of the Year, alongside Hillary Clinton, Aretha Franklin and Angela Davis, and singled out the risk she took in making such a public stand. But the 28 years since the pope picture ripping have been, she says, “incredibly isolating. To have been treated like a mental case because of it. Offstage and on. In private and in public. Even in my bed.”

“If they could have burned her at the stake,” Hanna says, “they would have.”

There have been times when O’Connor has been eager to call out those she felt wronged by. The list of targets is long, including family members, managers, friends, Bono, Madonna, Prince, even Geldof. She got into a public spat with Miley Cyrus after writing an open letter, in 2013, warning the singer “in the spirit of motherliness and with love” that her “Wrecking Ball” video showed she was being “pimped”. Three years ago, she accused Arsenio Hall of supplying Prince with drugs, sparking a $5m (£4.3m) lawsuit from the former talk show host, which he later dropped.

Though O’Connor acknowledges both being in and causing a considerable amount of pain, she also says some of the hurt was unintentional.

“My true nature,” she says, “is as a very loving person who doesn’t want to hurt people or cause hurt or to be hurt. That doesn’t mean that, as an artist, I would cease to challenge other artists. It doesn’t mean that I’m not f****ing Sinead O’Connor anymore. It just means I’m not a loose cannon.”

She’s found a kind of peace in Islam, adopting a Muslim name, Shuhada, though she continues to use Sinead professionally. The beauty of being a Muslim is that she doesn’t have to discard what she appreciates about other religions.

“Christianity lied to me as an Irish person,” she says. “Christianity did nothing but rape the people of Ireland, metaphorically and literally. That’s why I like Islam. Because I can take the things I embraced with me. Jesus is still there but it’s the Jesus that makes sense to me.”

Talking about the past, the conflict, can still be a trigger. It sometimes feels to her like it’s all anybody wants to talk about. And the past is a more complicated conversation for her at 53 than it was when she was in her 20s.

But Tiernan, bearded, in a knit cap and with sad eyes, seemed stricken. He decided to focus on suicide attempts and depression

“I don’t want to get the s*** kicked out of me anymore,” she says. “When I was young I could take a kicking. I’m too old to take a kicking now.”

O’Connor talks half-jokingly about the “right to be forgotten”, a still formative attempt in Europe to allow people to strip personal information off the Internet.

“Most people only have one or two awful things when you Google them,” she says. “But if you tried to do it with me, it’d take 100 years, wouldn’t it? I’d leave everything having to do with music. Take away all the other s***.”

It’s easy to understand why she wants to move on. The past – and explaining it – can be exhausting. Take her appearance in February on an Irish TV show hosted by Tommy Tiernan. She knew him as a comedian and walked onto the set with a smile, looking upbeat and ready to chat. But Tiernan, bearded, in a knit cap and with sad eyes, seemed stricken. He decided to focus on suicide attempts and depression.

One morning, after several days of interviewing with The Washington Post – both in California and in Bray – she shows up for breakfast feeling irritated and raw. And then the SNL incident is brought up. Again? Why, she asks, does everything have to be about the past? Her voice cracks and she wipes away a tear. Hasn’t she served her time?

Here in Bray, a resort town about 45 minutes from Dublin, O’Connor lives in an old house that was once a bed and breakfast. She’s got Hindu gods painted on her bedroom walls, a statue of the Mother Mary under the staircase and a wood-burning stove she’s just had installed to help cut down the gas bill. There is no trophy case or wall of gold records. O’Connor says she doesn’t think she ever claimed her Grammy and has no idea what happened to her MTV awards. If you didn’t know any better, it would be easy to miss the fact that a professional musician lived here. The only evidence is a few guitars in a back bedroom.

O’Connor doesn’t have a home studio or notebooks lying around filled with song drafts. She writes, she says, largely in her head. A melody will strike, the words will come and she’ll repeat the whole thing until it’s ready to be laid down as a demo.

An artist’s job sometimes is just to create conversation where conversation is needed. You drop the issue and then you run and you let everybody argue it out

Reynolds, her longtime producer, remembers O’Connor composing virtually all of 1994’s Universal Mother in a single night, simply singing into a tape recorder. She isn’t afraid to share her inspirations, whether the therapy time in “Milestones” or “The Last Day of Our Acquaintance”, about her relationship with former manager and one-time partner Fachtna O’Ceallaigh.

You can’t truly understand O’Connor without considering her homeland and what she lived through here. In the Ireland of O’Connor’s youth, the church and state ruled together. Divorce was illegal, sex was not to be discussed and “The Troubles” was the euphemism employed to describe the warring, largely between Catholics and the Protestants, that led to thousands of deaths. In this midst of this, during the 1970s, Sean and Marie O’Connor decided to separate. Sinead, not yet 10, ended up living with her mother, a regular churchgoer who also regularly and brutally beat her daughter. (These beatings were, she says, often when she was naked. In the past, she’s termed them sexual assaults).

Beyond her personal torment, O’Connor paid attention as reports of abuse in the church in Ireland began to circulate.

“When the pope came to Ireland when I was a kid, the first thing he did was get down and kiss the ground and say ‘Young people of Ireland, I love you’,” O’Connor says. “Yet the church was creating people like my mother.”

This was also around the time she found her key musical talisman. Her older brother, Joseph, brought home Bob Dylan’s 1979 album Slow Train Coming. It is the first of Dylan’s Christian albums and, at the time, was dismissed by music critics turned off by the religious themes. O’Connor found herself drawn to the songs.

“It was the first time you heard a priest being any way sexy,” she says of Dylan’s “Gotta Serve Somebody”.

The track "Slow Train" also resonated, with Dylan writing about the difference between believing in God and believing in men.

“But the enemy I see wears a cloak of decency,” he sang on “Slow Train”. “All nonbelievers and men-stealers talkin’ in the name of religion.”

The same tone of defiance carried over to the SNL incident.

Last May, when she got out of St. Patrick’s hospital in Dublin, she had less than $10,000 in the bank. She wasn’t bitter

After Marie O’Connor died in a car accident in 1985, Sinead took a photo of Pope John Paul II off her mother’s wall. In the fall of 1992, the singer began carrying it around, looking for an opportunity to use it. She was inspired by Geldof’s Boomtown Rats, who, in a 1978 TV performance, celebrated bumping “Summer Nights” from its chart-topping slot by ripping up a photo of John Travolta.

Pop singers are “supposed to shut up and be pretty and sing nice songs,” Geldof says. “Well, f*** off. And we learned that because that was the only option we had in Ireland. We were not going to be quiet anymore.”

Despite the backlash and the years of mistreatment, O’Connor has no regrets about the moment.

“An artist’s job is sometimes not to be popular,” she says. “An artist’s job sometimes is just to create conversation where conversation is needed. You drop the issue and then you run and you let everybody argue it out. I’m not at all sorry about it.”

In early February, O’Connor played San Francisco and then climbed into an SUV for the eight-hour drive south on Interstate 5, smoking butts and blasting Freddie King, Van Morrison and the intentionally offensive, fake country singer Wheeler Walker Jr., whom she finds hilarious. The trip included her first stop at In-N-Out Burger, where she was impressed by the patty but not the fries. In San Juan Capistrano, O’Connor and her band played the Coach House, a club with the feel of a saloon, long tables and waiters serving steaks and chicken strips.

At her peak, O’Connor played to thousands. The Coach House accommodates 480 people.

Backstage after her show, she met Rob Prinz, the co-head of worldwide concerts for ICM Partners, whose stable also represents Jerry Seinfeld and Bob Seger. Prinz told her he imagined bigger venues and a tour in the autumn to perform I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got in sequence. And though O’Connor was hobbled by a foot injury and too worn out from the long ride to bounce around excitedly at the idea, the fact that she was even in this place, talking business, was a measure of just how far she’d come.

Last May, when she got out of St. Patrick’s hospital in Dublin, she had less than $10,000 in the bank. She wasn’t bitter. The money she earned from stardom had lasted 30 years. To deal with bills, O’Connor sold the rights to her first four albums back to Universal Music Group. She then made plans to get back to work.

“Which is great,” she says. “Same as everybody else.”

The shows were stunning. In San Francisco, at August Hall, after shyly avoiding the audience for the first two songs, O’Connor lifted her head and smiled. The crowd erupted. At the Coach House, they screamed, “We love you, Sinead”, after she sang “Thank You for Hearing Me”, a hypnotic, 25-year-old song recorded after an emotional crash in the early 1990s.

Later that week, Kathleen Hanna heard that O’Connor was playing the El Rey in Los Angeles. What? She called Alaska Airlines and cancelled a planned trip to New York. Just a few months earlier, Hanna’s lifelong friend Allie Randall, with whom she listened endlessly to O’Connor’s music back in the late 1980s, had died of cancer. For days, Hanna had holed up, revisiting O’Connor’s first two albums.

At the El Rey, Hanna teared up as she watched from the balcony.

O’Connor had spoken up, spoken the truth so many times in the past, and they had tried to erase her. It was time to celebrate her return.

“Oh my God,” Hanna said out loud. “She’s back.”

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments