Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.What, one wonders, does David Lynch feel when he hears Lana Del Rey? Perhaps he’s flattered at the way she so skilfully personifies the precarious balance of danger and desire in his heroines? Or maybe he feels a little disturbed by her unflinching embodiment of this specific strain of his fictional characters: almost as if he’s being stalked by his own creation – which is, of course, a very Lynchian notion.

Honeymoon finds Del Rey reverting, after the more atomised, individual characters of last year’s Ultraviolence, to a composite persona closer to the dissolute subject of her Born to Die debut. Not only does her vocal delivery remain the same throughout, but also its protagonist’s “voice”; while the emotional impact of what might sometimes be traumatic developments seems somehow damped, as if experienced through a narcotised haze. Happy or sad, angry or apologetic, dominant or submissive, it’s apparently all the same to Del Rey, who floats through these songs with a weird indifference. It lends a sort of Stepford devotion to the more earnestly romantic songs, like “Religion” and “Music To Watch Boys By”, while prickles of danger are raised by the darker emotions: all it takes, in the separation ode “The Blackest Day”, is an offhand mention of a gun to spark the suspicion that, despite the bland delivery, this is an obsession teetering on the edge of either suicide or homicide. But when, in “24”, she complains, “You’re hard to reach/You’re cold to touch”, it’s hard not to think of pot and kettle locked in a mutually unfeeling embrace.

Musically, the template is established in “Honeymoon” and “Music to Watch Boys By”, with Del Rey’s affectless lead vocal borne on bleakly silken strings and the soft, multi-layered cooing of her background vocals, all featherbedded in a cocoon of airy reverb. It’s a miasmic, ethereal sound, its ghostly intimations of luxurious sensuality stippled with dreamy hints of danger which, in the closing cover version, transforms “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood” into the most sinister of torch songs. And when, in “Freak”, she entreats a potential lover with the invitation, “Baby, if you want to leave, come to California, be a freak like me”, it’s presenting the American Dream as a sort of numbed suspension in erotic aspic.

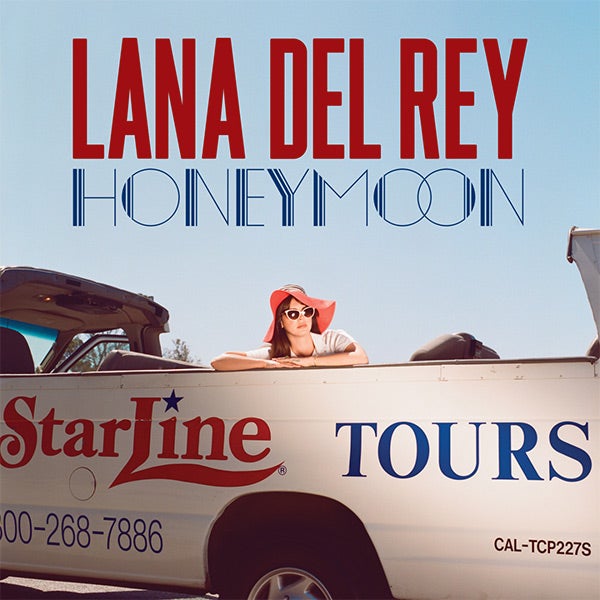

As the sleeve image – of Del Rey, leaning from a convertible advertising Starline Tours of celebrities’ homes – confirms, Honeymoon is a very Hollywood album, oozing Californian entropy. In “God Knows I Tried”, a reference to ““Hotel California” conjures up the mood of sun-baked dissipation, while she grudgingly confirms the dead-end revelation of celebrity, “I’ve got nothing much to live for, ever since I found my fame”. It’s a disillusioned rejoinder to the burning urge for fame that stains youth culture in the 21st century, and as such, fits in perfectly with the album’s overall sense of exquisite decay. Likewise, in “High By the Beach”, she realises, “I can’t survive if this is all that’s real”, slipping into a sunny but empty solace that renders excess as a slough of despond: “All I wanna do is get high by the beach”.

The only chink in the album’s smooth, shiny carapace of luxurious emotional imperviousness comes in “Salvatore”, where the sleek strings are underscored by a subtle Latin shuffle, while Del Rey adds the slimmest wafer of humour to the romantic chorus, “Matadoré/Limousine/Ciao amore/Soft ice cream”, as she licks her melting gelato in the front seat of a shiny convertible, en route to Mulholland Drive.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments