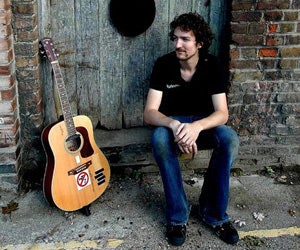

Frank Turner, Union Chapel, London

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The way a section of the crowd rise in their pews like a gospel choir tells you how fervently Frank Turner is loved by his fans. With his checked shirt and beard, he is no one's normal idea of a protest hero.

But he is signed to the legendary punk label Epitaph in the US, and began in the punk band Million Dead. His first solo EP, Campfire Punkrock (2006), fairly describes his music's urgent but reassuring pleasures, the train rhythms and mandolin strums easing down sometimes challenging words.

Europe's snowbound transport means he walks on stage late, straight from France. Luckily he's booked three kindred spirits as support. I catch Chris T-T, a relative veteran of modern UK protest pop. His mournful refrain, "find a job, get a Nintendo", captures a mix of self-disgust and resignation at the mediated, corporate world. Dion's 1968 memorial to assassinated Americans, "Abraham, Martin and John", drips with kitsch sentiment, but he approaches it straight.

When Turner finally appears, the self-described militant atheist looks round this beautiful church at Christmas-time and hopes for "a church service – but without God". The mulled-wine-merry screams from the pews certainly offer devotion. A sing-along to Wham's "Last Christmas" stands in for a carol, and "Journey of the Magi" nods to the spiritual in sympathy for a dying, idealistic Moses.

But Turner's mix of scrubbed perkiness and suppressed rage can't manage transcendence. It's his songs about relationships, not society, that feel raw. "Hold Your Tongue" tries to vengefully draw tears from an infuriating acquaintance, while "Faithful Son" is truthfully fraught in describing this son's love for his parents. One of his heroines may "smoulder with the will to save the world". But he is too aware of how ephemeral such efforts are to believe in the "revolution" plotted "from a cheap Southampton bistro" in "I Knew Prufrock Before He Got Famous". "The Ballad of Me and My Friends" is his hardly Marxist, or even Dylanesque, manifesto. It's about the individual artistic impulses more and more of us follow, that fade to dust, forgotten, but allow striving, full lives, so who cares? The front rows leap up at its first notes, and Turner rips through a sawn-off version. He could dig deeper. But he is keeping some embers of mild resistance alive.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments