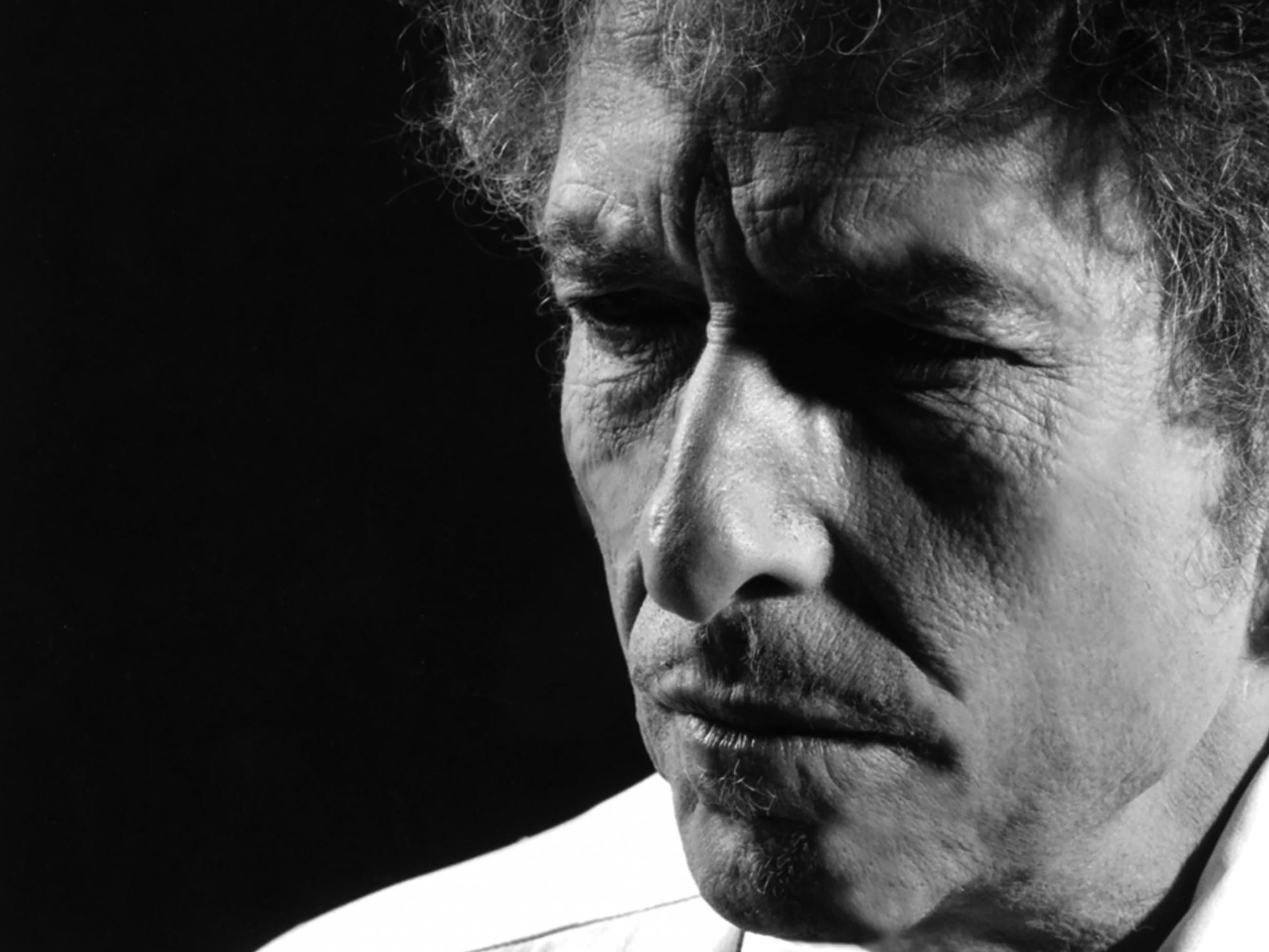

Bob Dylan review, Rough and Rowdy Ways: There’s real consolation in the easy-going embrace of his contradictions

His first new material since 2012’s ‘Tempest’ is a soothing fit for the lockdown mood in which time and meaning feel strangely stretched and untethered

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Bob Dylan became the first songwriter to win the Nobel Prize in Literature back in 2016, he “got to wondering how my songs related to literature”. Instead of delivering his acceptance speech in person like most people, Dylan recorded one. In his “roundabout way”, he concluded that meaning is irrelevant; that story, sound and feeling are all that matter. So, like an ancient bard, he retold three classic tales – Moby Dick, All Quiet on the Western Front and The Odyssey – over the meandering tinkle of a cocktail piano.

His richly soporific new album – his first new material since 2012’s Tempest – plays like an extension of that speech: a folksy recitation of literary and pop references sprawling over long, ramshackle songs with minimal (mostly acoustic) melodies that sway back and forth behind him like curtains in a light breeze. Quotes from Homer, Shakespeare and Blake are shuffled with winks at Stevie Nicks and Patsy Cline. It’s a soothing fit for the lockdown mood in which time and meaning feel strangely stretched and untethered.

Fans will already have heard “Murder Most Foul”, the 17-minute epic that recasts the assassination of John F Kennedy as a Greek tragedy and gets its own CD here. The event that represented the Boomer generation’s loss of innocence occurred when Dylan was just 22 years old. He’d released his second album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, six months earlier and had already finished recording his third, The Times They Are a-Changin’. His next album would find him turn away from protest songs and look inward in a way that angered many in the earnest folk scene.

This month, he’s been looking and speaking out again. He’s called the killing of George Floyd “beyond ugly” and hoped that “justice comes swift”. He’s spoken out against the “arrogance” of our leaders in dealing with the pandemic. So when “Murder Most Foul” finds him lamenting “the age of the Antichrist”, he might have the Trump administration in mind. Although it’s all – as ever – anyone’s guess.

The track’s mood is a still, grey sky. Over a gentle wash of piano and cello, the 79-year-old Dylan – whose car now sports a World’s Best Grandpa bumper sticker – croaks: “Twas a dark day in Dallas, November ’63/ A day that will live on in infamy…” The early rhymes and clichés are a bit naff. Unlike Leonard Cohen, who famously took years over his lyrics, Dylan’s always been as likely to toss off lines as to hone them. This means “Murder Most Foul” takes a while to get going. But it’s worth hanging on for “What’s new, pussycat? What’d I say?/ I said the soul of a nation’s been torn away/ and it’s beginning to go into a slow decay/ and that it’s 36 hours past judgment day.” He’s talking about then and now. He tells us how to get through terrible times. Acknowledging the inevitability of sorrow and decline, he offers the solace of songs like last rites: “Play ‘Lucille’/ Play ‘Deep In a Dream’/ And play ‘Driving Wheel’/ Play “‘Moonlight Sonata’ in F-sharp… Don’t worry, Mr President/ Help’s on the way.”

Other songs find him in lighter mood. “I Contain Multitudes” toys with the writer’s long-time self-mythologising and is sardine-packed with delightful rhymes. The title, lifted from Walt Whitman, is played off against blood feuds, painted nudes, Bowie’s “all the young dudes” and Chopin preludes – although the games come with menaces. Dylan warns: “I’ll sell you down the river, I’ll put a price on your head/ What more can I tell you?/ I sleep with life and death in the same bed/ Get lost, madame, get up off my knee/ Keep your mouth away from me…”

Death shifts from the “madame” of “Multitudes” to assume the form of a bounty hunter on the flamenco-flecked “Black Rider”. “Tell me when, tell me how,” asks the old gunslinger, “If there ever was a time then let it be now/ Let me go through, open the door/ My soul is distressed, my mind is at war.”

I have a tendency to be irked by floor-pacing repetitions of barroom blues. Those Dylan offers here – “False Prophet”, “Goodbye Jimmy Reed” and “Crossing the Rubicon” – contain the restless ghosts of old 45s spun on his Theme Time Radio Hour. They do add texture. But with so little happening in the melodies I prefer the tracks where the music remains an acoustic backdrop. I loved the horizon-wide breaths of accordion sustaining the dreamlike “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)”. This song finds Dylan’s voice – once described by Joyce Carol Oates as “sandpaper singing” – sounding wonderfully bleached and cracked. Like something Tom Waits left out in the sun. It’s warm and wise as the singer quotes Otis Redding’s “Try a Little Tenderness”.

Dylan ended his Nobel lecture reminding us that: “Songs are alive.” It’s true. Most of these new ones have a soft and sleepy pulse, although the blood flowing through them reflects difficult times and a difficult man. They’re equal parts finger-pointing and forgiveness. At a time of polarised debates, there’s real consolation in Dylan’s easy-going embrace of his contradictions and complexity.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments