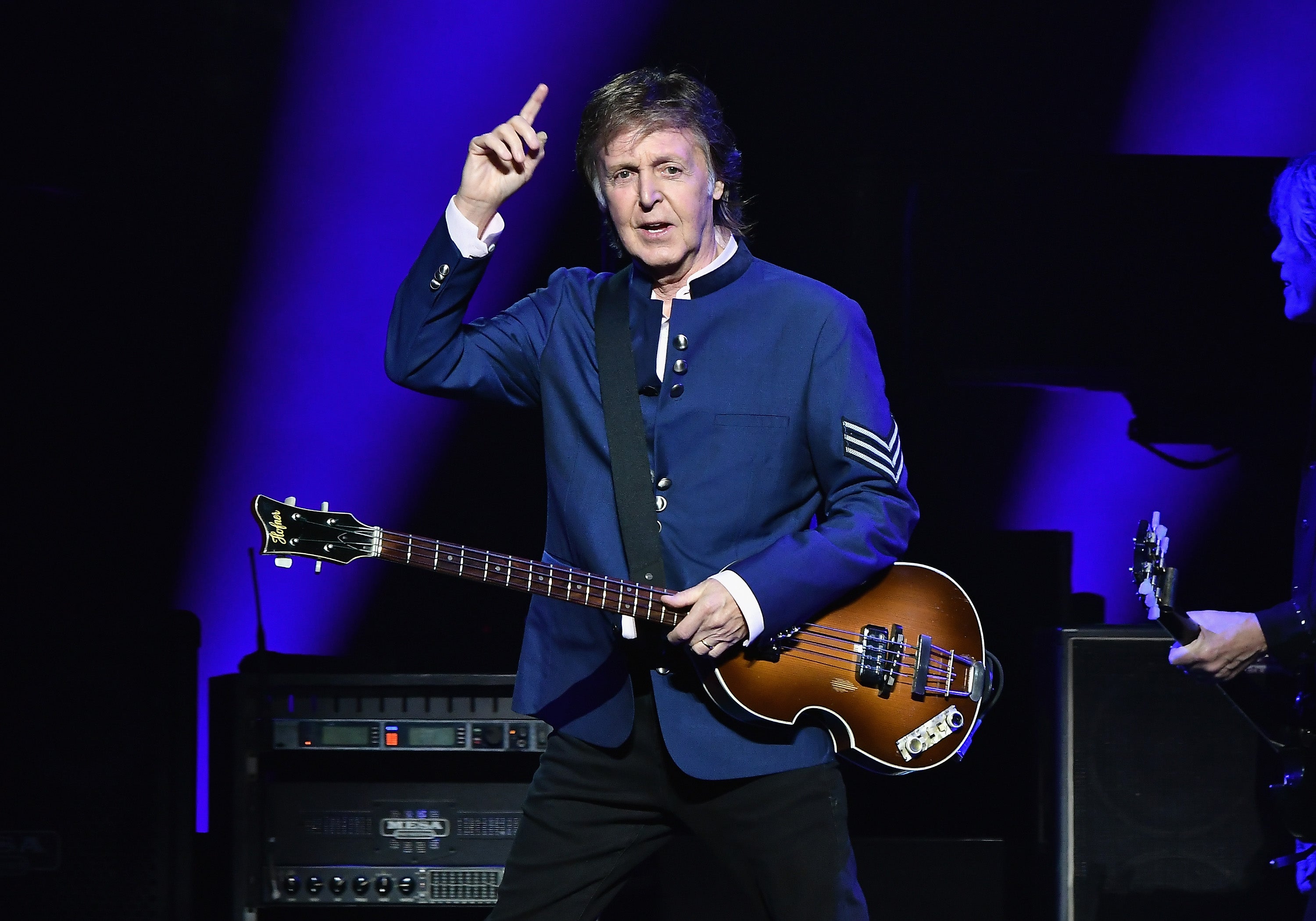

Paul McCartney: What we learned from new doc ‘McCartney 3,2,1’

The Beatle takes a leisurely trip through musical memories and anecdotes, guided by super producer Rick Rubin. It makes for some magical moments, writes Kevin E G Perry

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

Paul McCartney, now 79, has not been a Beatle for more than 50 years. Any fears that time and familiarity may have withered his excitement for the songs he wrote as a young man is quickly dispelled in the new three-hour docuseries McCartney 3,2,1, which captures the music icon in conversation with legendary producer Rick Rubin while listening to the band’s original master tapes, specially retrieved for the purpose from Abbey Road.

It’s a simple format that sparks magic.

Take, for example, one of the series’ most delightful moments. McCartney tells the story of seeing trumpeter David Mason play a piccolo trumpet during a BBC broadcast of a Bach concerto and deciding he’d be perfect for a solo on “Penny Lane”. The tale is one thing – the inside story of how an incredibly familiar piece of music came to be – but McCartney’s reaction to hearing the original recording played loud is quite another. The camera lingers on him as he air trumpets along, sheer ecstatic joy painted all over his face.

McCartney 3,2,1 is by no means a definitive documentary about the life and times of the planet’s greatest living songwriter, but it doesn’t set out to be. It flows as freely as a conversation. As McCartney and Rubin talk, they jump back and forth through his incredible career, touching on music from Wings and cult favourite album McCartney II as well as the old Beatles favourites. The result is relaxed, loose and always charming. There’s a particular focus on a lesser-talked about aspect of McCartney’s genius: his inventive, melodic bass playing. At one point, listening to “With A Little Help With My Friends”, Rubin observes: “It’s like a lead bass, essentially.”

Rubin is an excellent host for this format, which is another way of saying he knows when to shut up and listen. He keeps his contributions to a minimum, just steering McCartney with enough questions and prompts to keep his memories flowing. At several points, including when McCartney offers to play him “Thinking of Linking”, the first song he ever wrote at age 14, Rubin literally sits cross-legged at the feet of the master. It comes as no surprise when the producer reveals that, as a teenager himself, he learned to meditate because it was something The Beatles did.

There is only one moment in the series where Rubin, or perhaps the producers, make a misstep. It comes in the fifth episode, when Rubin presents McCartney with a quote about what a great and innovative bass player he is before revealing that it was ostensibly said by John Lennon. McCartney appears touched. “That’s John?” he asks. “All right! Come on, Johnny! That’s beautiful. I hadn’t heard that before.” The truth is Lennon’s quote from a Playboy interview has been doctored, removing a dig about McCartney otherwise being an “egomaniac”. Knowing this, the scene rings a little hollow.

Generally McCartney 3,2,1 doesn’t try to force moments of sentimentality like that, because it doesn’t need to. McCartney’s stories stand on their own. In the first episode, he describes the moment a roadie asked him to pass the salt and pepper: “And I thought he said Sergeant Pepper.” McCartney evokes the moment of inspiration striking with characteristic modesty.

“We had a laugh about it, but then the more I thought about it I thought: ‘Sergeant Pepper, that’s kind of a cool character’,” he reveals. The same goes for all the ideas he and Lennon got from hearing Ringo’s malapropisms, or “Ringoisms”, which became song titles like “A Hard Day’s Night” and “Tomorrow Never Knows”.

Perhaps the most exciting moments for Beatles devotees come when McCartney digs deep into his relationship with Lennon. He neatly sums up their differing personalities with examples from their songwriting (McCartney would write a line like: “It’s getting better all the time”, to which Lennon would reply: “It couldn’t get much worse.”) and talks in depth about how they would push each other’s songs into unexpected directions.

In one memorable sequence, McCartney recalls Lennon playing him a fast-paced song he’d just written, “Come Together”, before they realised it was too close to Chuck Berry’s “You Can’t Catch Me”. McCartney’s suggestion that they slow it down to a swampy groove takes the song in a whole different direction, and to a place only The Beatles could have reached.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

McCartney 3,2,1 is maybe not the first film you’d choose to show to someone who’d never heard of McCartney or The Beatles, but for old fans and aspiring musicians alike it contains enough fresh stardust to make it feel like a thrilling few hours spent in the company of a genuine musical genius. More than that, it will send you back to The Beatles with new ears and a fresh appreciation for how a few lads from Liverpool changed music forever.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments