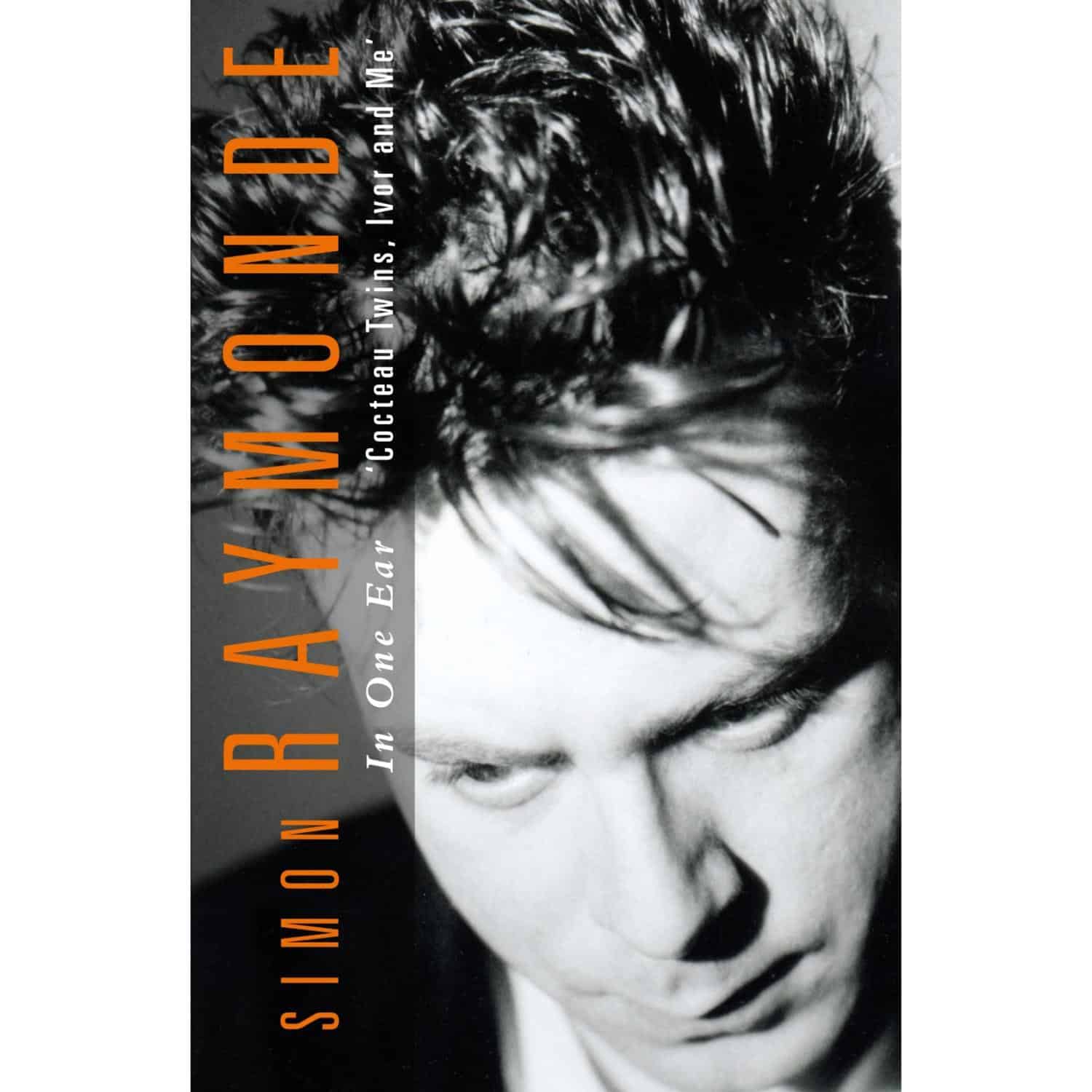

Simon Raymonde: ‘I started to hate who I was becoming’

The musician and label boss has released his first memoir, ‘In One Ear’, in which he reflects on his career with the Cocteau Twins, a brain tumour diagnosis and navigating the music industry as a manager

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Simon Raymonde looks back on record deals, kidnappings, childhood, terror attacks, band breakups and brain tumours in his new memoir, In One Ear: Cocteau Twins, Ivor Raymonde and Me.

Having first risen to fame as the bassist for influential Scottish dream-pop band Cocteau Twins, Raymonde went on to found one of the UK’s most successful independent labels, Bella Union, which has released albums by artists including Fleet Foxes, Father John Misty, John Grant and Ezra Furman.

Speaking to The Independent, Raymonde, 62, admitted he’d never considered trying to put his life into a book until he bumped into musician and composer Warren Ellis, who had just completed his own memoir.

“I don’t dwell – I’m the sort of person who just gets on with things,” he explained. “It’s useful in this business, sort of like self-preservation… I wouldn’t be alive without it, there’s no doubt about that.”

He continued: “I think a result of getting older is that I don’t really care what people think about me anymore, because eventually you realise that it’s quite fruitless and there’s not a lot of good to come out of worrying. You just do what you do.”

Raymonde maintained this attitude even as he was diagnosed with a brain tumour in 2001, after he suffered sudden hearing loss in one ear. “[Going deaf] felt a bit like when you go swimming and suddenly your ear is blocked but you can’t get the water out. It felt like that.”

After a hearing test, he was sent for an MRI scan, which revealed the tumour on the right side of his brain. Doctors warned that removing it could cause damage to his nervous system: “I just said, thanks very much, but no thanks.”

Raymonde returned home “kind of terrified” but determined to seek out a second medical opinion: “What he told me filled me with a kind of confidence. It’s a very slow-growing tumour, so I go back and have scans every year, but it hasn’t really grown significantly,” he said.

He was working at a record shop, Beggars Banquet, in Wandsworth, London, when he met Robin Guthrie and his then-girlfriend, singer Elizabeth Fraser, who were attempting to deliver a cassette to the label 4AD. Two years later, he’d joined their band in time to record and release their first top 40 album, 1984’s Treasure, continuing with Guthrie and Fraser as a trio until their split 13 years later.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

In the book, Raymonde reflects on the tumult that led to the band’s demise: “I hadn’t dealt with it [before], because it was just so complex,” he told The Independent. He struggled to cope with his bandmate Guthrie’s cocaine addiction: “Drugs had been around for a while, and I’d started to notice that I didn’t like the behaviour of other people in our circle.

“Then I found myself taking too much, because when you’re in a band with someone who’s an addict, sometimes it’s just easier to give into the peer pressure. You don’t want to be the party-pooper. So you do it, but two hours later, you’re paranoid and depressed and feeling like s***,” he said.

“I did that for a year or two until I started to hate who I was becoming, but luckily I was aware of that, so it wasn’t a case of, ‘Oh f*** it, let’s have some more.’”

Getting clean “really affected” his and Raymonde’s relationship, the musician said. “Having previously said yes, I think he just sort of assumed that I was judging him. And I understand why he would think that – why anybody would think that if they had those problems.”

“Addiction strained the relationship – not just mine and his, but clearly his and Elizabeth’s,” he continued. It was “ironic” that Cocteau Twin made “probably our best record” through the worst times: “In hindsight, I think Robin believed that it was because of the drugs, whereas I’d assumed we would naturally get better and better, as more experienced and better musicians. That was why [1990’s Heaven or Las Vegas] was good, not because Robin was off his nuts.”

Both fans and the music press still subscribe too much to the “tortured artist” trope, he said: “I know that, because I think we made some beautiful music while we were all completely sober. But it’s very easy to buy into that, because I suppose it justifies it, to them. If you get critical acclaim for something that you made while you were off your head, it’s like, ‘Well, it’s fine to do it, then.’ And there are hundreds of casualties in that world who believed that hype.”

Raymonde said he believes that his experiences as an artist have helped him in his work as the head of Bella Union, the management side of which he runs with his wife, Abbey Raymonde.

“Sometimes without meaning to you can become quite parental, and that can cause problems because you get too close, and then it hurts when [an issue] doesn’t get resolved, and it all blows up in your face,” he said. “But I think I wrote in the book that I’d rather be close and have it go wrong occasionally than be distant and not really care about [the artists] as much.”

He had a breakthrough when he discovered and signed a record deal with Fleet Foxes, whose self-titled debut album went on to sell a million copies in Europe. But Raymonde, who writes that he cried when he first heard the band’s music, rejected the notion of signing an act based on sales or streaming numbers.

“I do kind of worry that [the passion for discovering new music] might go,” he said. “It does, right? I would definitely have to do something else, because you’ve got to really care to be able to dedicate the hours and the effort for such tiny rewards. You have to love doing it. And most of the time, I do.”

‘In One Ear: Cocteau Twins, Ivor Raymonde and Me’ by Simon Raymonde is out now via Nine Eight Books

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments