People looked for ‘one thing’ in pictures of Shane MacGowan, photographer Andrew Catlin says

Exclusive: Renowned photographer remembers working with the Pogues frontman and Sinead O’Connor, both of whom died this year

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.People typically looked for one thing in pictures of Shane MacGowan, photographer Andrew Catlin has said: a shot of the late Pogues frontman with his mouth agape, those infamous teeth on display.

Catlin, a photographer, director and filmmaker whose work is on display at the National Portrait Gallery, reflected on his memories of working with MacGowan – and his friend and fellow musician, Sinead O’Connor – after attending the Anglo-Irish singer’s funeral in Dublin.

One of the most famous shots of MacGowan, taken by Catlin, was seen on the artist’s coffin as the funeral procession took place, and later displayed during the service at St Mary of the Rosary Church.

“They wanted a picture of his mouth open, his teeth all showing looking as grotesque as possible,” Catlin told The Independent of how many people expected to see the “Fairytale of New York” singer.

“That’s all everyone ever wanted for a long-time and it seemed to me that it was really irrelevant.”

As both a friend and a photo subject, MacGowan could be “very difficult”, Catlin said, “but he was never nasty”.

“He was either bored or he didn’t want to engage with you,” he explained. “And then he would just switch off and ignore everything. He could be in a room full of people and not be there at all – people thought he was always completely out of it, but he just wasn’t interested in whatever was going on.”

If someone happened to say something that caught MacGowan’s interest, though, he would “snap out of it” and come out with “an incredible, intelligent, well-informed opinion”.

“He was so sharp,” Catlin said. “And he was incredibly interested in people – if they weren’t interesting, that’s when he’d switch off. And he didn’t like people who were full of s**t.”

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Some of Catlin’s favourite portraits of MacGowan were taken in Porto, Portugal, around 1989, while the band were going through a particularly difficult period.

“Shane was going crazy because they’ve been touring nonstop for like four years or something, and he was acting more and more like he didn’t want to be there,” Catlin recalled. “You could really see it was starting to unravel at that point.”

Catlin and MacGowan stayed up drinking all night, until the musician decided he was willing to do a photo session.

“He was acting out the madness that was going on in his head, and he kind of transformed into all these different characters,” Catlin said. “There’s one where he looks like he’s being crucified, and another where he’s got a fistful of cash.

“It was always fantastic working with Shane – you just had to wait until the mood was right.”

Catlin met MacGowan’s friend, Sinead O’Connor, when he was commissioned to shoot the then-21-year-old for a music magazine. After missing his flight to Los Angeles, he feared he’d lost the gig, but a twist of fate meant that, around a month later, he discovered that O’Connor had moved into the flat two floors above his.

O’Connor died aged 56 in July, a year after the death of her son Shane.

“She was just an extraordinary character, you know?” Catlin said. “She wasn’t at all arrogant – she was interested and curious.

“This was before she’d had a hit record, but she’d already been through so much in life. Yet she maintained this incredible openness her whole life – most people become really guarded after a long time in the music industry.”

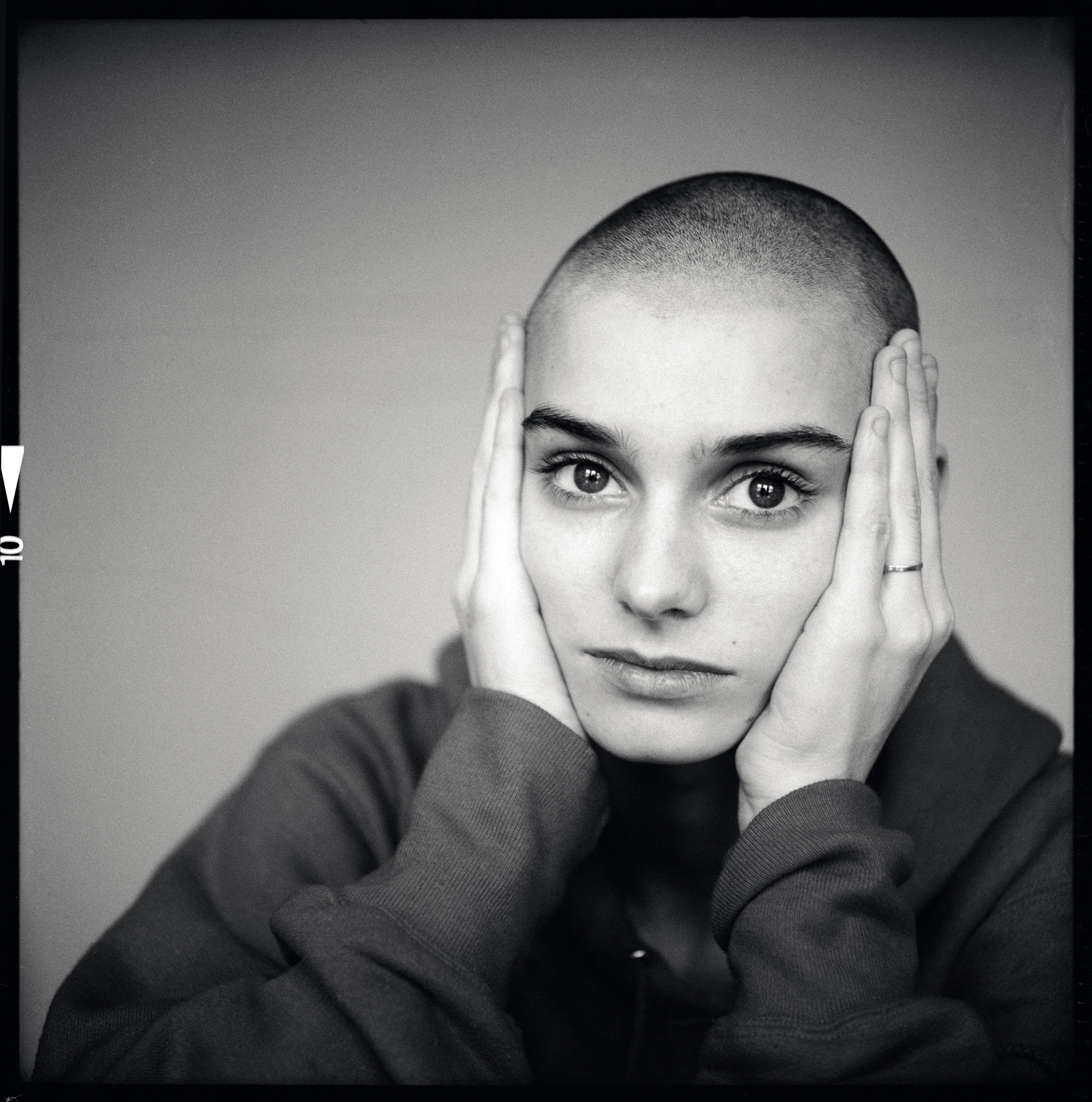

Catlin’s photos of O’Connor show her wide-eyed, gazing into the lens, with her hands clasped to her face. Her hair is freshly shaved: “The record company told her to wear more makeup and get dressed up, so she shaved her hair off,” Catlin said.

The pair met often after that first shoot. The last time Catlin saw her was at MacGowan’s 60th birthday at the National Concert Hall in Dublin, which “celebrated Shane surviving to 60”.

“He was presented with some kind of lifetime achievement award at the end, which I think he was very moved by – as someone who grew up outside Ireland but loved it and spent a lot of time there,” Catlin said. “That was quite an important thing for him.”

MacGowan’s funeral, attended by thousands of fans along with the musicians close friends and family, was an “amazing experience”, he said, and “absolutely in keeping with everything he was about”.

He found himself seated in one of the front pews near MacGowan’s former Pogues bandmates, and Michael D Higgins, president of Ireland.

“It lasted for more than three hours, and it was absolutely electric for every second of it,” he said. “It was emotional, beautiful, funny and extraordinary.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments