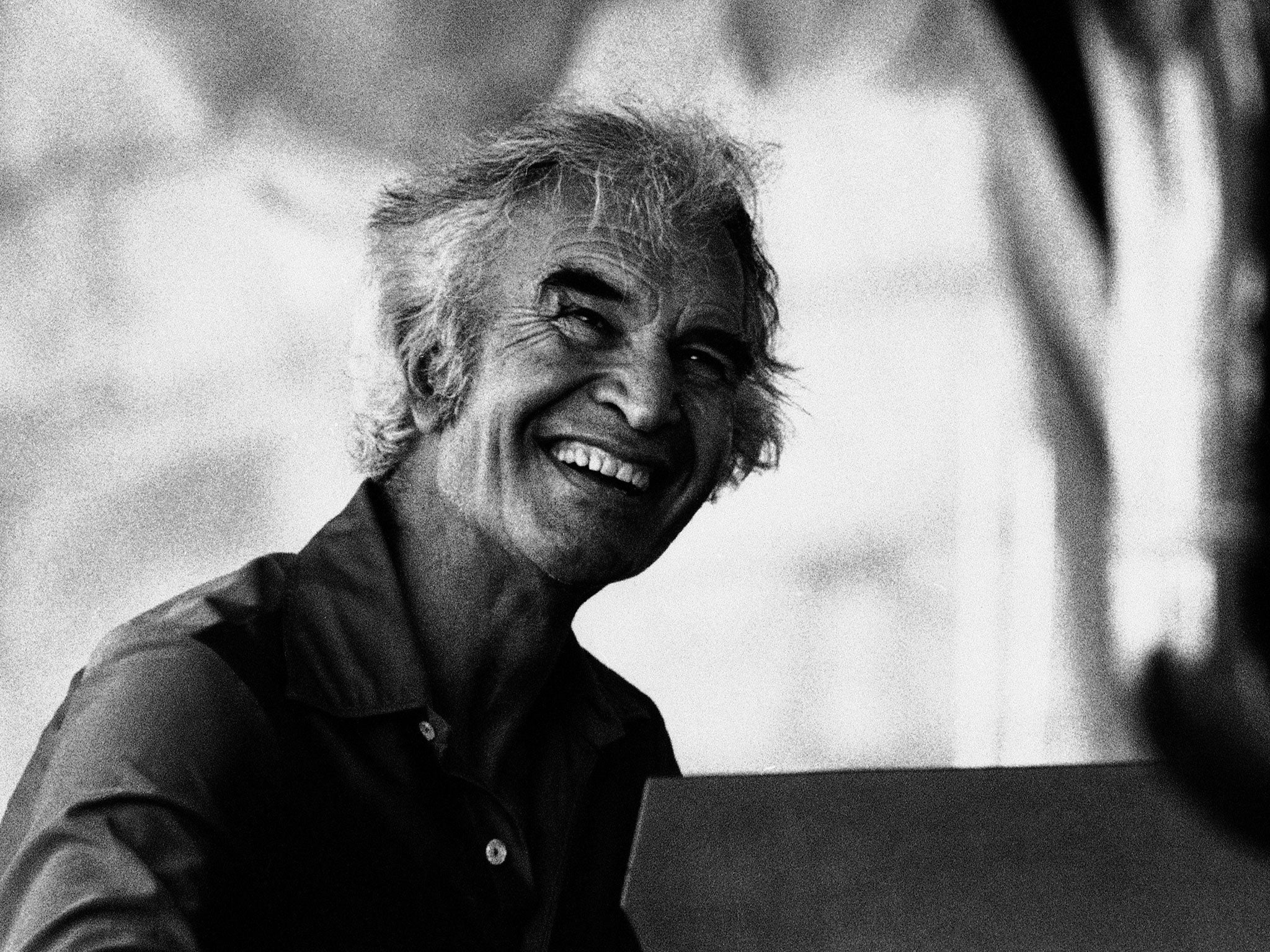

Pianist behind one of the world's most famous jazz tunes takes his final five

Dave Brubeck has died aged 92

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Dave Brubeck, who died in hospital this morning, the day before his 92nd birthday, didn't write "Take Five", the million-selling tune which defined his career to a large public and remains one of the most famous in jazz.

That was the work of Paul Desmond, the saxophonist in Brubeck’s quartet who played its sinuous solos as Brubeck’s percussive piano swung in 5/4 time. But it was Brubeck who was, as much as anyone, the unlikely, white, bespectacled face of jazz in the 1950s.

His manager Russell Gloyd told the Chicago Tribune that Brubeck died in hospital in Connecticut on Wednesday of heart failure while on his way to a cardiology appointment.

Born in Concord, California, on 6 December 1920, his early ambition was to follow the career of his cattle-rancher father Howard. But it was the example of his frustrated concert musician mother Elizabeth which would win out. Classically trained either side of service in World War Two, his tutor the French composer Darius Milhaud gave him good advice for the post-war, pre-rock USA: “If you want to express this country, you will always use the jazz idiom.”

Brubeck formed his first band in 1948, an octet typically mixing then cutting-edge bop with swing and neoclassical styles. Other great jazz pianists of his generation such as Bill Evans and Bud Powell worked among the hard-living titans of the bop generation which formed in sepulchral after-hours jams in New York night-club Mintons in the 1940s, with brooding bandleaders such as Miles Davis and Charlie Parker and their sometimes harsh-angled, challenging improvisations. Brubeck offered a different world.

The Dave Brubeck Quartet were West Coast cool, a favourite of college crowds throughout the 1950s. Brubeck restlessly challenged himself, most obviously by switching into outlandish time-signatures (“Blue Rondo a la Turk”, the second most famous tune on the 1959 album Time Out was in 9/8) but it always sounded breezy and fun.

Brubeck, though an entirely unpretentious, amused and amusing man, had something of the affable, quietly hip professor about him. Columbia marketed his many hit albums of the 1950s and early 1960s with modern art on the sleeves, and Jazz Goes to College was among of series of similarly scholarly titles. He was never a deep underground cult, but a name to drop, and a gateway into jazz’s darker and choppier waters. Prog-rock keyboardist Keith Emerson was among the many British musicians of the period who learnt from him, before forging their own divergent worlds. Emerson remembered shaking with nerves when he approached his hero for a signature in the 2000s, as the pianist, then pushing 80, played yet another gig.

When Time magazine put him on their cover on 8 November 1954, before “Take Five” had even sealed his fame, Brubeck was embarrassed, believing jazz’s greatest composer, Duke Ellington, should have been far ahead of him in the queue, and that it was his race which had made him acceptable.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments