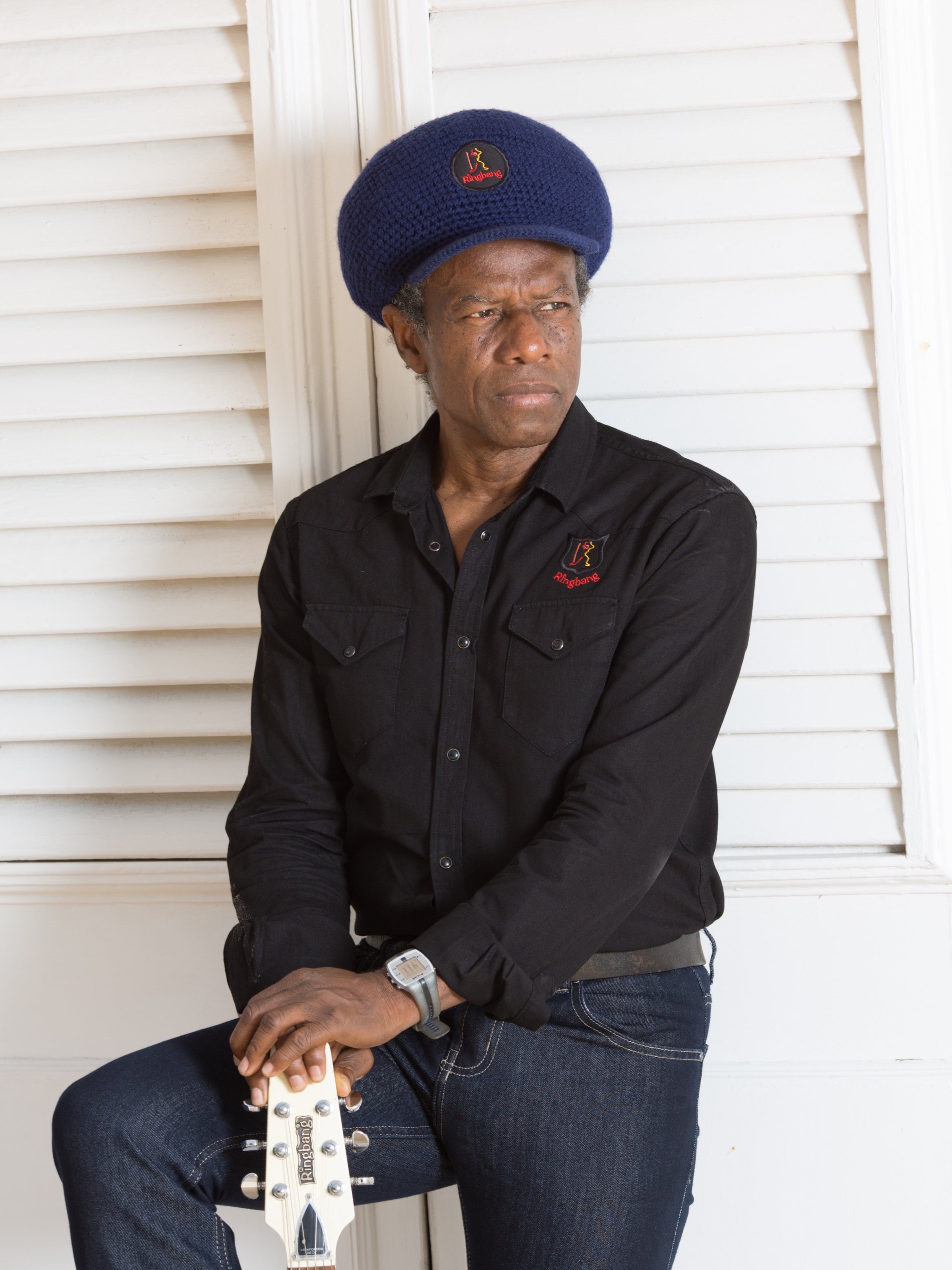

Eddy Grant says British government treated Windrush Generation like ‘enslaved Africans’

Exclusive: The pioneering singer, 75, called on King Charles to take a lead on making reparations for the UK’s role in the slave trade

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Pioneering singer Eddy Grant has said that the British government brought over the Windrush Generation like “enslaved Africans”, and called on King Charles to begin the process of making reparations for the UK’s role in the transatlantic slave trade.

Guyanese-born Grant, who immigrated to London in 1960 aged 12, branded the term “Windrush Generation” a “b*****s phrase coined by the media” and said he was frustrated by “the fact that the Caribbean people, who are basically Africans in this particular case, are labelled with a misnomer”.

“We are not a generation of Windrushes, we are a set of people who, in the face of England’s loss of youth during the wars, had to be brought in, [on a] very similar basis and terms as the enslaved Africans, the first time around, who were taken to their empirical territories,” the “Electric Avenue” singer, 75, told The Independent.

“From my perspective, I hear talk about [the] Windrush Generation, and it’s really all b*****s,” Grant said. “There is no Windrush Generation. It’s a phrase coined by the media.”

He added: “We’ve accepted, again by force of media, a name or designation that doesn’t belong to us.”

The singer spoke with The Independent from Guyana while Mashramani festival celebrations got underway, as he released his landmark album Killer on the Rampage to digital streaming services for the first time.

Grant, who met the then-Prince Charles in 2001 at Capital FM’s Party in the Park in aid of the Prince’s Trust, spoke highly of the King as he called on him to “do the right thing” and begin the process of reparations.

“In my estimation of the man, when we were in conversation – I found him extremely easy to speak to, and I have to say quite knowledgeable,” Grant said. “Which makes you ask, why can he not do what he knows to be the right thing?”

Acknowledging that the British monarch is currently being treated for cancer, Grant said he believed King Charles could help bring an end to “what is such a heinous, terrible and disgusting issue”.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

“For all [his] talk of inclusivity, [this] can not ever be realised as long as reparations are not enacted,” Grant said.

In September last year, it was reported that Caribbean nations were preparing formal letters to demand that the British royal family apologise and make reparations for slavery.

Speaking to The Telegraph in Grenada, Arley Gill, a lawyer and chair of the island nation’s reparations commission, said: “We are hoping that King Charles will revisit the issue of reparations and make a more profound statement beginning with an apology, and that he would make resources from the royal family available for reparative justice.”

Meanwhile, Labour MP Bell Ribeiro-Addy, chair of the all-party parliamentary group (APPG) on Afrikan reparations, said in October that the UK had a “moral duty” to face up to the past.

“The UN, other governments, religious institutions and NGOs have all accepted they need to address their role in the enslavement of African people and the legacy of racism and impoverishment it left behind,” she told The Independent.

Grant has spent a career spanning six decades calling for such justice through his music, but sounded frustrated at the lack of progress made. His 2006 album, Reparation, referred to his calls for restitution for the translatlantic slave trade.

“You kind of wonder what is it that’s driving this division, if you like to call it that, that it moves from generation to generation,” he said. “I look at things with a very caustic eye. And I don’t have to be sitting in the middle of England [to feel affected by it]. It’s kind of a shame that we don’t seem to move on.”

He was, however, pleased that music fans still seemed to find themes that resonated in his music: “It’s amazing,” he said. “But then you can only say so much and then it sounds like you’re boasting.”

Grant was born in what was then known as British Guiana, a colony that became the independent nation of Guyana in 1966. He emigrated to the UK in 1960 to join his parents, who had already moved there to work, and later rose to fame in the mid-Sixties as one of the earliest artists to popularise reggae and Caribbean music in the UK and around the world.

With his potent blend of reggae, soul, funk, pop and other genres, Grant was a founding member of The Equals, one of Britain’s first racially diverse bands. He later achieved success as a solo artist with his Grammy-nominated 1983 single “Electric Avenue”, as well as his anti-Apartheid anthem “Gimme Hope Jo’anna”.

Killer on the Rampage is out now on all digital platforms.