Every artwork featured in Beyoncé and Jay-Z's 'APES**T' music video

From classical icons, to the greats of French Romanticism

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As part of the surprise release of Beyoncé and Jay-Z's joint album EVERYTHING IS LOVE, the pair also released a video for the track "APES**T".

Directed by Ricky Saiz, who had previously worked on Beyoncé's "Yoncé" video, as part of her self-titled 2013 visual album, it's the only visual offering so far from the nine track-album - though it's truly spectacular on its own terms.

Namely, the deep, symbolic messaging that accompanies the Carters' own takeover of Paris' Louvre museum, one of the most famous cultural spaces in the world, which has widely been interpreted as an act of decolonisation within a historically white space.

Indeed, the six-minute video features some of the most important pieces of the Western historical art canon, now challenged and reinterpreted by both Beyoncé and Jay-Z's own placement in front of and interaction with the works in question.

You can see a full list of the pieces included below, alongside time codes for when they first appear.

(0:39) Mona Lisa

Artist: Leonardo da Vinci

The mysterious subject at the centre of the portrait is believed to be the wife of a Florentine cloth merchant named Francesco del Giocondo; notably, none of her garments indicate aristocratic status. However, it seems the portrait never made it into its subject's possession. Rather, da Vinci appears to have held on to the work until his death, after which it passed into the François I's collection.

(0:59) Victory of Samothrace Landing

Artist: Unknown

A depiction of the goddess Nike, the personification of victory, the statue once stood at the prow of a marble ship, as part of an ornamental fountain on the island Samothrace. It is believed to date from the 2nd century BC, created as a commemoration of a naval battle.

(1:08) The Oath of the Horatii

Artist: Jacques-Louis David

David's first royal commission, in 1784, shunned the mythological for a subject of sober historical significance - in particular, stoicism and patriotism - focusing on the end of the war between Rome and Alba, in which both cities chose champions to fight, the Horatii and Curiatii respectively. The painting depicts the Horatii swearing their loyalty, ready to sacrifice themselves for Rome, while the women are prostrate with grief.

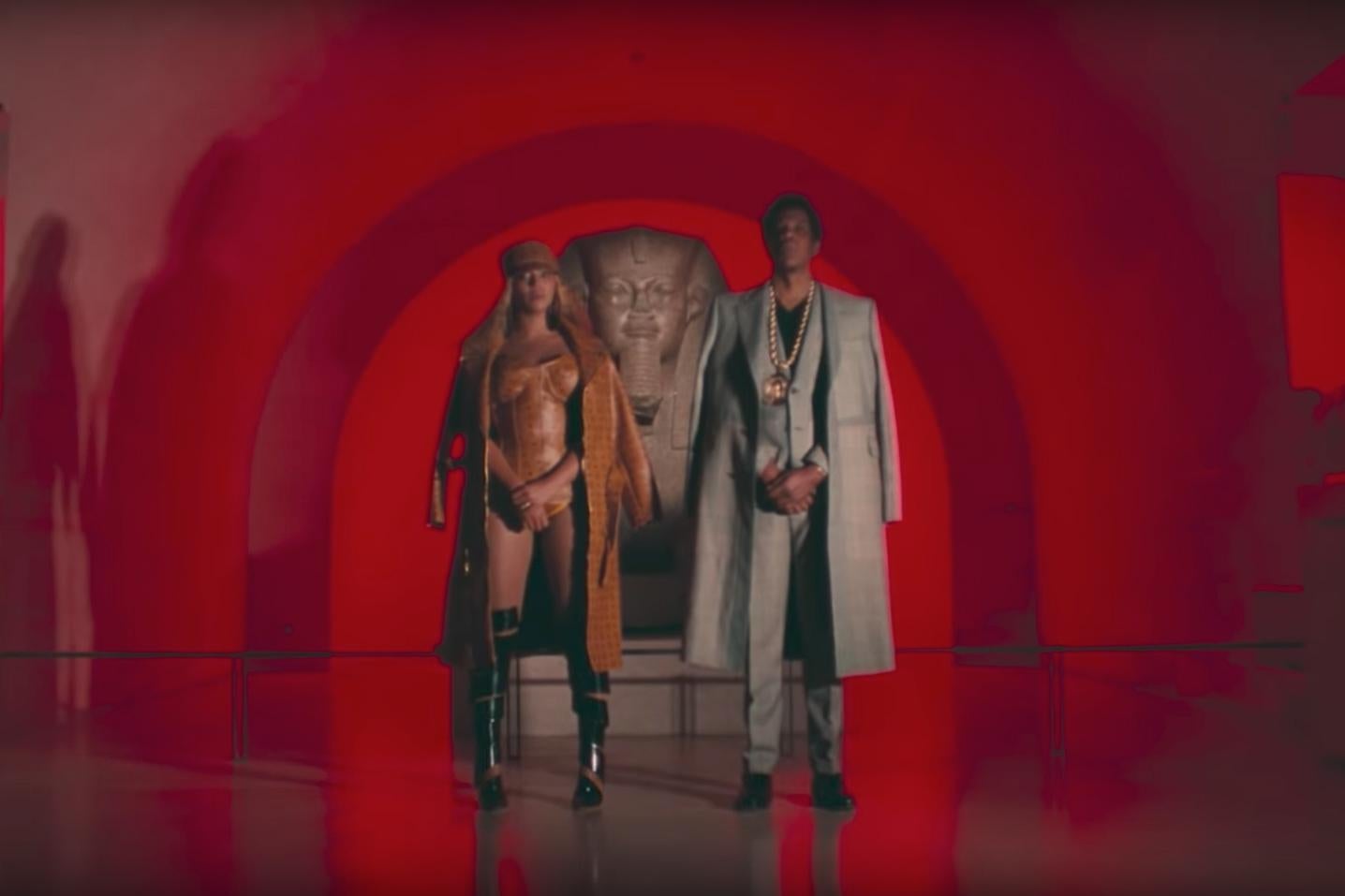

(1:22) The Great Sphinx of Tani

Artist: Unknown

Believed to date back to the Old Kingdom of Egypt, c.2600BC, this is one of the largest sphinxes now housed outside of Egypt itself, taken from the ruins of the Temple of Amun at Tanis in 1825. It bears the inscriptions of pharaohs from throughout Egypt's early history, including Ammenemes II (from the 12th Dynasty, 1929-1895 BC), Merneptah (from the 19th Dynasty, 1212-02 BC), and Shoshenq I (22nd Dynasty, 945-24BC).

(1:37) The Consecration of the Emperor Napoleon and the Coronation of Empress Joséphine on December 2, 1804

Artist: Jacques-Louis David

Commissioned by Napoleon I to depict his confirmation of power, this huge canvas shows the moment the newly-crowned Emperor bestows the title of Empress upon Joséphine. He crowned both himself and Joséphine at the coronation, though it was a ceremony traditionally carried out by the Pope.

(1:58) The Intervention of the Sabine Women

Artist: Jacques-Louis David

A part of Rome's founding myth, David's work captures the Sabine women - who had been abducted by the Romans - rushing into the midst of the battlefield to end the fighting, as the Sabines attempted to rescue them. A celebration of peace,

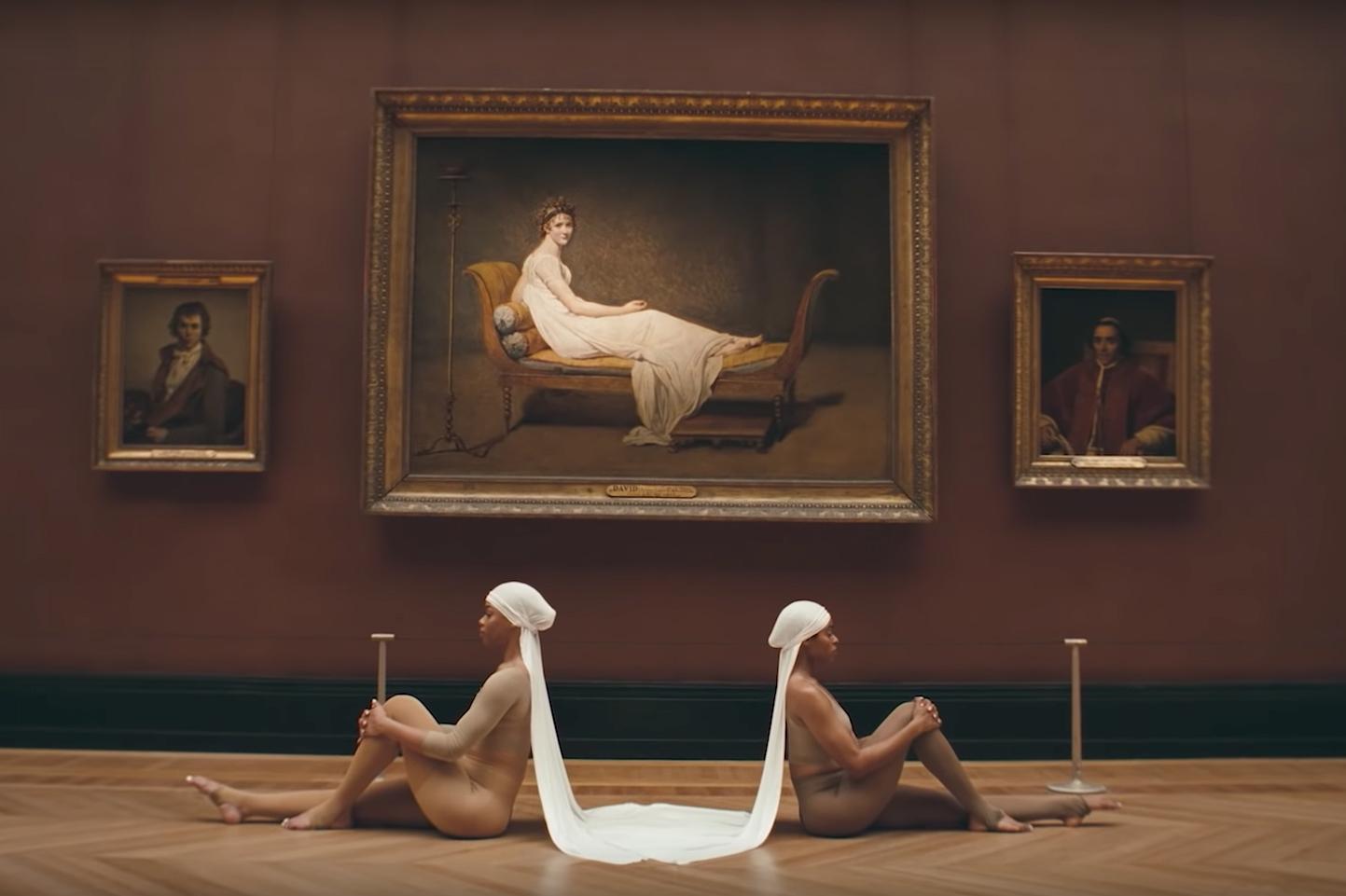

(2:15) Madame Récamier

Artist: Jacques-Louis David

Juliette Récamier, the wife of a Parisian banker, became one of the most famous socialites of the early 1800s; however, this portrait never came into her possession. David was keen to rework the painting, but she grew impatient and commissioned one of his students to paint her instead. It remained unfinished upon his death.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

(2:38) Les ombres de Francesca da Rimini et de Paolo Malatesta apparaissent à Dante et à Virgile

Artist: Ary Scheffer

Three very similar versions by Scheffer exist - one in the Wallace Collection, one in the Hamburger Kunsthalle, and the third in the Louvre - which show a scene from Dante's Inferno, in which Dante and Virgil meet Francesca and her lover Paolo in the second circle of hell, trapped in an eternal whirlwind because of their passions.

(2:46) Pietà

Artist: Rosso Fiorentino

Once hung above the chapel door at Château d'Ecouen, the residence Anne de Montmorency, Constable of France, the work shows the Virgin Mary at its centre, arms outstretched in agony as the body of her son is held before her by Mary Magdalene and St. John.

(3:12) The Raft of the Medusa

Artist: Théodore Géricault

Interpreted as an anti-imperialist and abolitionist work at the time, it places a black man as the centre of its composition: a depiction of the aftermath of the wreck of the French naval frigate Méduse, sent to colonise Senegal in 1816, which became an international scandal and an indictment of ultra-royalism of the time.

(3:22) The Charging Chasseur

Artist: Théodore Géricault

A heroic show of bravery depicted on the rider's face contrasted with the frantic nature of the horse, it was the first work Géricault entered into Paris' famous the Salon, in 1812, and representative of his move away from classicism towards romanticism.

(3:33) Hermes Fastening his Sandal

Artist: Lysippos

A Roman copy of a lost Greek bronze, in the manner of Lysippos, the subject isn't clearly identifiable as Hermes or simply an athlete in an idealised form.

(3:51) Venus de Milo

Artist: Unknown

Taken from the island of Melos in 1820, its identity is similarly conflicted: she may be Aphrodite, the Greek equivalent to Venus, or the sea goddess Amphitrite. The arms were never found. She may even be a replica, created during the Hellenistic Period, c. 100 BC, but inspired by an original from the late 4th century BC.

(4:30) The Wedding Feast at Cana

Artist: Paolo Veronese

A depiction of the biblical feast at which Christ performs his first miracle, turning water into wine, Veronese's work is also a representation of the height of 16th-century splendour. Amongst the wedding guests are the likes of Francis I of France, Mary I of England, Suleiman the Magnificent, the tenth sultan of the Ottoman Empire, and the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V.

(5:36) Portrait of a Black Woman

Artist: Marie-Guillemine Benoist

Painted in 1800, after the emancipation decree of 1794 which liberated slaves within the French colonies and abolished slavery, only for it to be reinstated by Napoléon Bonaparte in 1802, the work has been interpreted as a romanticised portrait of a newly freed slave, as linked to a growing feminist movement within France at the time.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments