You probably weren't singing the original version of Auld Lang Syne last night

And the melody wasn't even written by Robert Burns

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

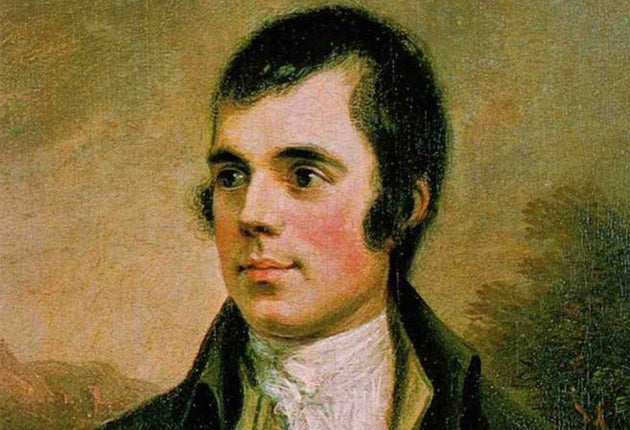

Your support makes all the difference.Auld Lang Syne was famously written by the Scottish national bard, Robert Burns. What is less well known is that the melody was not the one he intended. The one that became famous was first attached to the song in the late 1790s and Burns, who died in 1796, knew nothing about it.

The man who published the soon-to-be-famous song was an Edinburgh song editor, George Thomson. Burns had told him a few years earlier that a melody was usually his starting point for writing a song. Yet his inspiration in 1788 when he wrote Auld Lang Syne, which translates roughly as Old Time’s Sake, was actually not a melody but an existing song with the same opening line – “Should auld acquaintance be forgot”.

Scholars have dated versions as far back as the 16th century, to a song called Auld Kyndnes Foryett. Burns himself would have known several versions that were popular in print and performance throughout the 18th century. His song is much closer to these versions than the 16th-century original. One of these, by the poet Allan Ramsay, is set against a backdrop of war and talks of the parting of lovers. Burns typically opens this out and makes it more universal.

When he sent his version of Auld Lang Syne to his great friend Frances Dunlop in 1788, he told her he’d heard an old man singing it. There’s no evidence of who this man might have been – and Burns may even have fabricated the story to show how close he was to popular culture.

The melody switches

When Auld Lang Syne was first published in the Scots Musical Museum collection in 1796, it was joined to a rather slow and haunting tune. This melody really brings out an element of sadness in the text. It has found new popularity in recent years, but we don’t know whether Burns chose it or not. He told George Thomson in 1793 that he didn’t think much of the tune commonly sung to existing versions of the song.

Thomson needed no more encouragement to switch to the melody that we know today. Much more celebratory in feel, it had appeared in some earlier 18th-century fiddle collections and was often referred to as The Miller’s Wedding or The Miller’s Daughter. By the time Thomson had made the decision to marry the tune to Burns' text, the poet had died and there was no chance of asking his opinion on the matter. But certainly Burns would have known it, since he wrote another song called O Can Ye Labour Lea (1792) for a variant of the same tune.

Thomson characteristically forged ahead and sent the tune to Vienna, where the Bohemian composer Leopold Koželuch set it for voice, piano, violin and cello. Auld Lang Syne then appeared in Thomson’s Select Collection of Original Scottish Airs in 1799, set to the famous tune for the first time. From then on, it gathered popular momentum across the British isles and beyond through social gatherings – often Masonic ones – and in many theatrical productions.

Nae gowans, nae stowps

When we chant Auld Lang Syne this New Year, we’ll probably sing only a couple of Burns’ original verses. We’ll leave out the drinking verse where we fill our “pint stowp” (pint cup) and the rather affectionate verses about “paidl’d in the burn” (paddled in the stream) or “pu'ing the gowans fine” (picked the daisies fine). Instead we’ll concentrate only on looking back, remembering fondly and joining hands of friendship.

Why the song became world famous is still something of a mystery, though all that socialising and theatre-going in the 19th century must have helped. Burns had died in considerable debt and it really is too bad that performing rights were a thing of the future. As many will be aware, Happy Birthday has been a gold mine for Warner Music over the years. While Auld Lang Syne sits right beside it as one of the most popular songs of all time, it never made any royalties for anyone.

There is a virtual exhibition about Auld Lang Syne on the University of Glasgow project website, Editing Robert Burns for the 21st Century.

Kirsteen McCue, Professor of Scottish Literature and Song Culture, University of Glasgow

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments